When COMMIT Is the Slowest Query

When COMMIT is the slowest query, it means your storage is slow.

Let’s look at an example.

Normally Slow

Normally, application-specific queries are the slowest—maybe a complex SELECT that has to examine a lot of rows but lacks a good index.

In that case, you know what to do: optimize the query.

(And if you don’t know how to do that, then you’ve not read chapter 2 of my book.)

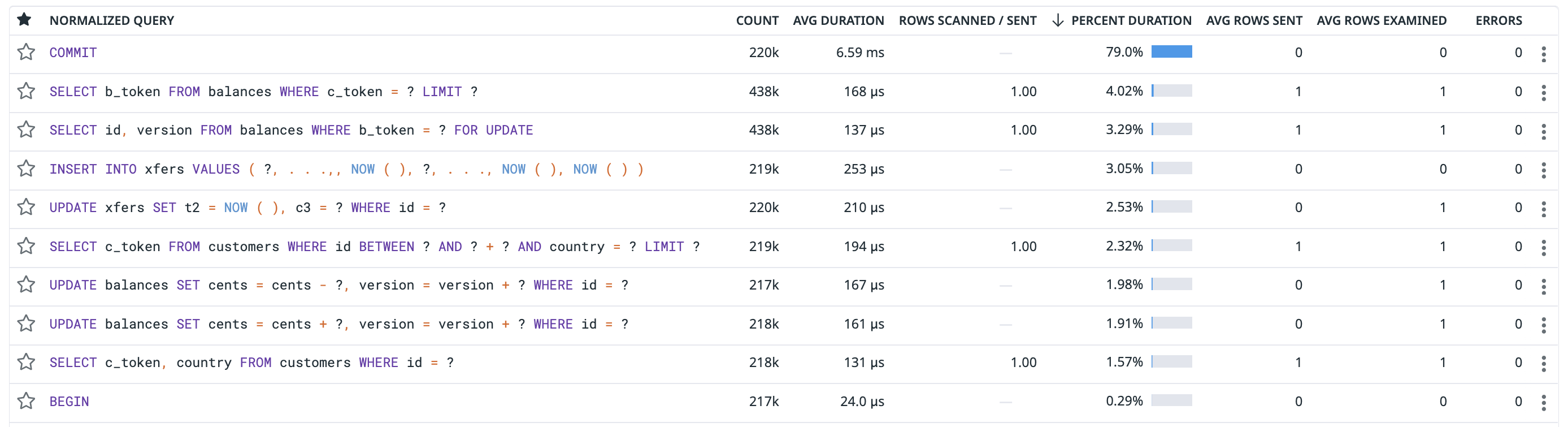

But what if COMMIT is the slowest query, like shown below?

Click the image to see the full size.

The image above is Datadog Deep Database Monitoring (DDM) showing standard query metrics sorted descending by percentage of total query time. (And if you don’t understand that, then you’ve not read chapter 1 of my book.) Since I strive to remain neutral and focus on the tech, I’ll say two things in the spirit of neutrality:

- Datadog DDM is a good commercial solution for MySQL query metrics.

- Percona Monitoring & Management is free open source solution for MySQL query metrics.

For the moment, I’m using Datadog DDM because I wanted to see if and how it reports a known workload: the Finch xfer benchmark.

The slowest query in this case is COMMIT for two reasons:

- MySQL is using network-backed storage

- All other queries are highly optimized

Network-backed storage, which is the norm in the cloud (but there are exceptions), is normally slow: on the order of milliseconds for a local network.

(Actually, local networks should have microsecond latency, but database storage in the cloud usually spans two or more availability zones [data centers], so the network is local to the region, which pushes latency to low single-digit milliseconds.)

This is evidenced by the average COMMIT response time reported by Datadog: 6.59 ms.

That’s normal for network-backed storage.1

Don’t Be Fooled by the Average

The average is a bad statistic for database performance metrics because it’s often misleading. (Average database/table size is fine, but that’s about it.) To learn more, you know what book to read (chapter 1, section “Average, Percentile, and Maximum”).

Datadog reports 6.59 ms average COMMIT response time.

But Finch, which is running the benchmark, reports (milliseconds):

| Min | P50 | P95 | P99 | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.6 | 6.5 | 14.1 | 17.4 | 20.9 |

In this case, the P50 (50th percentile/median) happens to be nearly identical to the average, but this is only coincidence.2 Do not presume average and median values for any metric are close; you cannot know until you measure.

The average isn’t terrible for network-backed storage, but the higher percentiles and max tell a very different story:

COMMIT response time doubles from the median and average (blue bars) to the P95 and higher (orange and red bars).

Moreover, since the average is virtually equal to the P50 in this case, thinking that COMMIT is ~6 ms ignores the most important half of the picture: the slow half that’s most annoying to users.

This is why P95 and higher percentiles are better statistics: they ignore less of the picture.

In my book, I argue that none of the picture should be ignored (therefore, the max value is most important); but realistically, blips and flukes do occur, so the P99 or P999 (99.9th) are good trade-offs.

In this case, even the P95 shows that COMMIT is much slower than the average: 14 ms and slower.

How to Fix Slow COMMIT

Presuming the database server isn’t terribly misconfigured3, the only way to fix slow COMMIT is to use faster storage with lower write latency.

Sorry but that’s it because COMMIT latency is a direct reflection of storage write (and flush) latency.

(If you don’t know why, then you haven’t read chapter 6 of my book.)

This is especially true for Amazon Aurora for MySQL because it uses a proprietary modification of the InnoDB storage engine, so log and page flushing concerns that affect normal MySQL are more opaque, which means COMMIT on Aurora is handled by Aurora and there’s nothing users can do about it.

When COMMIT latency in the cloud becomes the barrier to better performance, there are two extreme solutions:

- Sharding

- Not using MySQL

With respect to sharding, if you can’t get the write performance you need with one MySQL server, than use N-many MySQL servers.

It won’t lower the storage/COMMIT latency, but it will allow for greater transaction throughput.

And no, it’s not easy, but often times it’s necessary.

(You know what I’m going to say in this parenthetical: this time, it’s chapter 5 of my book.)

Since I already mentioned one commercial solution, let me throw in another related to sharding: PlanetScale.

With respect to not using MySQL, it’s as “simple” as that: use a different type of data store with faster write performance. But do not expect magic: true durability requires writing and flushing to disk, so every truly durable data store is limited by storage latency. The only difference is that some data stores are write-optimized, so the limit is further away than it is with MySQL.

IOPS and Redo Log

Everything above presumes IOPS aren’t an issue. Since I was running Amazon Aurora, IOPS are virtually unlimited—pay per use. (But check out Amazon Aurora I/O-Optimized.) And the redo log is different with Aurora.

If you’re running anything else (other than Aurora), IOPS and redo log will be limited and either could be the reason COMMIT is slow.

You can only tell by monitoring the relevant InnoDB I/O metrics, which will show you both IOPS usage and what I call “write pressure” (how close the redo log is to a forced flush point).

All that’s covered in chapter 6 of my book.

But as a quick tip: if you’re running on bare metal with locally attached SSDs (not spinning disks), then it’s very unlikely any of this—IOPS, I/O latency, or redo log size—is an issue, or that COMMIT is slow.

It’s mostly a problem affecting MySQL in the cloud on network-backed storage.

Spinning disks also have millisecond write latency. But I haven’t seen spinning disks on a production database server in more than a decade. I hear they still exist, though. ↩︎

A bit more than coincidence: it’s a synthetic workload, so the distribution of response times is probably normal, which means average and median coincide due to the “balanced” workload. ↩︎

On normal MySQL,

COMMITmight be slow because innodb_log_file_size is terribly undersized. ↩︎

Copyright 2025 Daniel Nichter