Replica Preserve Commit Order and Measuring Lag

With multi-threaded replication (MTR), a replica can commit transactions in the same order as the source, or not.

This is determined by sysvar replica_preserve_commit_order (RPCO).

As of MySQL v8.0.27 (released October 2021) it’s ON by default, but it was OFF by default for several years prior.

In either case, it’s relatively new compared to 20+ years of single-threaded replication for which commit order was not an issue or option.

But with MTR, it’s important to understand the affects of RPCO, especially with respect to the focus of this three-part series: replication lag.

This is a three-part series on replication lag with MTR and the Performance Schema:

| Part | Topic |

|---|---|

| 1 | Group commit and trx dependency tracking |

| 2 | Replica preserve commit order (RPCO) |

| 3 | Monitoring MTR lag with the Performance Schema |

Links to each part are in the upper right ↗ (or top on small screens). This part presumes you’ve read part 1.

For simplicity in the following diagrams, let's pretend each numbered trx (1–10) is also its timestamp from the source. So trx 1 committed at t=1 on the source. And furthermore, let's pretend trx 10 just committed, so now = 10. Units are seconds.

Single-threaded

Compared to MTR, single-threaded replication is trivial and replica commit order isn’t an issue because there’s only one order with one thread.1

Let’s say we have 10 transactions (trx), from the replica point of view:

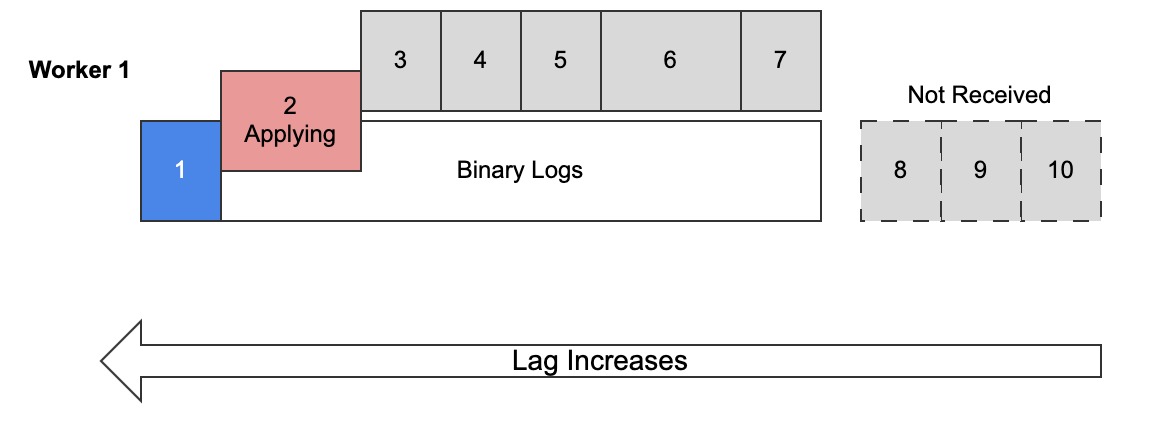

Diagram 1: Single-threaded replication

Diagram 1 shows:

- Trx 1 (blue) has been applied (committed) by the replica into its binary logs

- Trx 2 (red) is actively applying but not committed yet

- Trxs 3–7 (grey) have been received (in replica relay logs not shown) but not applied yet

- Trxs 8–10 (grey, dashed outline) have not been received yet but they exist in the source binary logs

There’s no question of order: trx are applied in the order they’re received, which means they’re applied in on the replica in the same order they were committed on the source. In this example, that order is 1 to 7, then 8 to 10 once those trx have been received.

Apply vs. Execute

Read Why MySQL Replication is Fast to learn why replicas apply transactions, not execute them.

With single-threaded replication, lag equals now minus the timestamp of the trx being applied by the SQL thread.

In diagram 1, lag = 10s (now) - 2s (trx 2) = 8s. If nothing else changes, the replica should catch up to the source (apply trx 10) in 8 seconds.

Why not calculate lag as now minus trx 7? Because trx 2–7 can be lost. Trx 2 might fail to apply. Even if it doesn’t, the replica could crash right after trx 2 and purges its relay logs (trx 3–7) for crash-safe replication recovery.2 Since relay logs can be large, reporting lag this way would be misleading because in terms of durably applied trx the replica is 8s behind, not 3s.

Last important point with respect to single-threaded replication: there cannot be any gaps, like trx 1 and 3 are applied but trx 2 is not. A single threaded replica never skips transaction.3 This makes reasoning about and measuring single-threaded replication lag easy, but MTR is a different story.

MTR and RPCO

As of MySQL v8.0.27 (released October 2021), replica_preserve_commit_order is ON by default, which is a good default.

| Version | RPCO Default |

|---|---|

| ≥ 8.0.27 | ON (Enabled) |

| ≤ 8.0.26 | OFF |

Not coincidentally, in chapter 7 of Efficient MySQL Performance, which was written around the time of 8.0.25, I advised setting RPCO on (contrary to the default at the time). A rare case of a technical book being ahead of its time.

Since RPCO was off for several years, there’s probably hundreds of thousands of MySQL instances running with it off. Let’s understand what it affects when it’s off or on.

The following diagrams use the same conventions as diagram 1, but they show two worker threads instead of one.

RPCO OFF

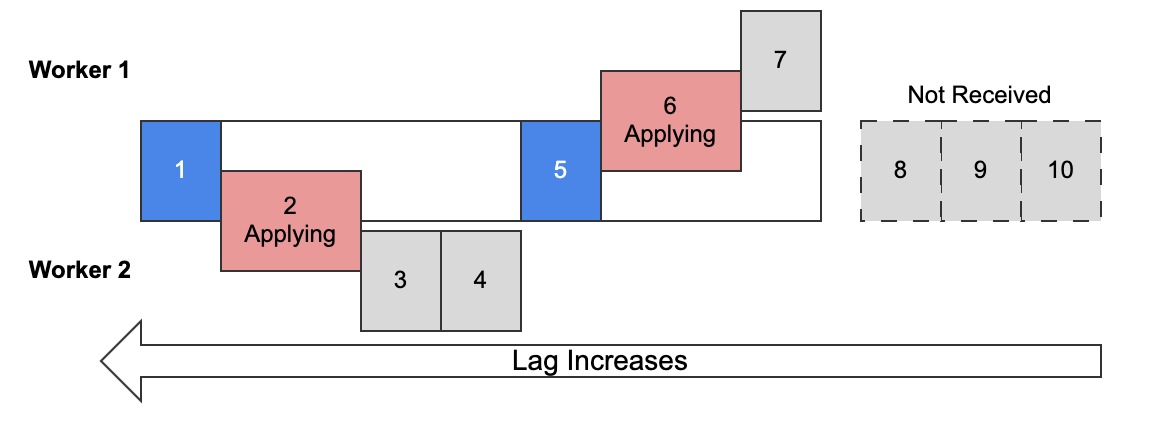

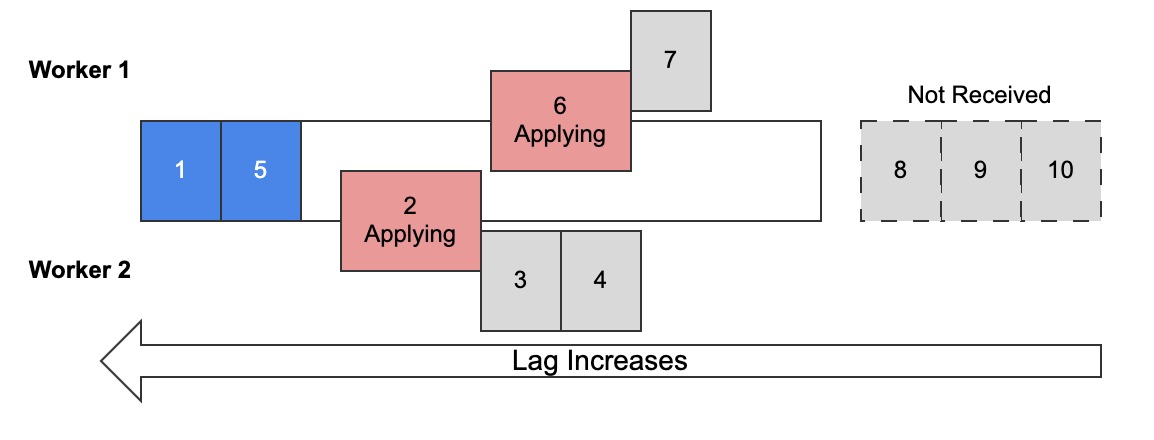

Diagram 2: Simplified view of multi-threaded replication with replica preserve commit OFF

Diagram 2 shows the old default: replica_preserve_commit_order = OFF for MySQL ≤ 8.0.26.

Worker 1 is assigned trx 5, 6, 7.

Worker 2 is assigned trx 1–4.

Blue is committed and red is applying (not committed).

Since RPCO is off, each worker applies and commits transactions in parallel.

(The emphasis on “and commits” will be important later.)

Diagram 2 is not wrong but the visualization makes it look like MySQL will fill in the gap between trx 1 and 5, which is not what happens when RPCO is off. Diagram 3 is technically more accurate and more likely:

Diagram 3: Realistic view of multi-threaded replication with replica preserve commit OFF

Since trx apply in parallel and RPCO is off, trx can (and probably will) be committed by the replica in a different order than the source. As a result, the source and replica will have different transaction histories. (A transaction history is an ordered set of committed transactions.) This may or may not be a problem.

Different transaction histories are not a problem for MySQL or data consistency because—as explained in part 1: Group Commit and Transaction Dependency Tracking—the source already determined that these trx are independent and, therefore, can be applied in parallel. Eventually, the replica will apply all 10 trx (in this example) and then, despite different transaction histories, both source and replica will have identical data. It’s like source and replica take different routes to the same destination: eventually, they arrive at the same place.

However, different transaction histories might be a problem for programs that read from the replica. If, for example, your app reads from replicas, you already know that data is eventually consistent because of replication lag. (I presume you’re using async replication not [semi-]synchronous options.)

Eventual consistency is easy to reason about: the data is old; wait and eventually it’ll become current. But with RPCO off, a different challenge arises that’s less easy to reason about: data might be simultaneously old, new, and missing. This is what diagram 3 shows: trx 1 is old, trx 5 is newer, and the changes from trx 2, 3, 4 are currently missing.

Again, this is not a problem for MySQL because it’s not using the data; MySQL has no semantic awareness of what the data means. But the app and the humans using it do, which raises the question: would a state of data like diagram 3 make sense or cause a problem for the app? If you choose to turn RPCO off, that’s the question you need to answer.

Transaction gaps are a challenge for replication lag: is the lag 8s (measured from trx 2) or 4s (measured from trx 6)? (Recall that each trx takes 1s to execute and trx 10 represents the current time.) DBAs tend to agree that the conservative, low watermark is the better answer: 8s.

With MTR, replication lag is measured from the oldest applying (or last applied) transaction. There’s additional nuance to this approach that part 3, once published, will explain.

Without careful consideration of application logic, replica_preserve_commit_order = OFF is not a safe assumption.

Consequently, as of MySQL 8.0.27 replica_preserve_commit_order is ON by default.

RPCO ON

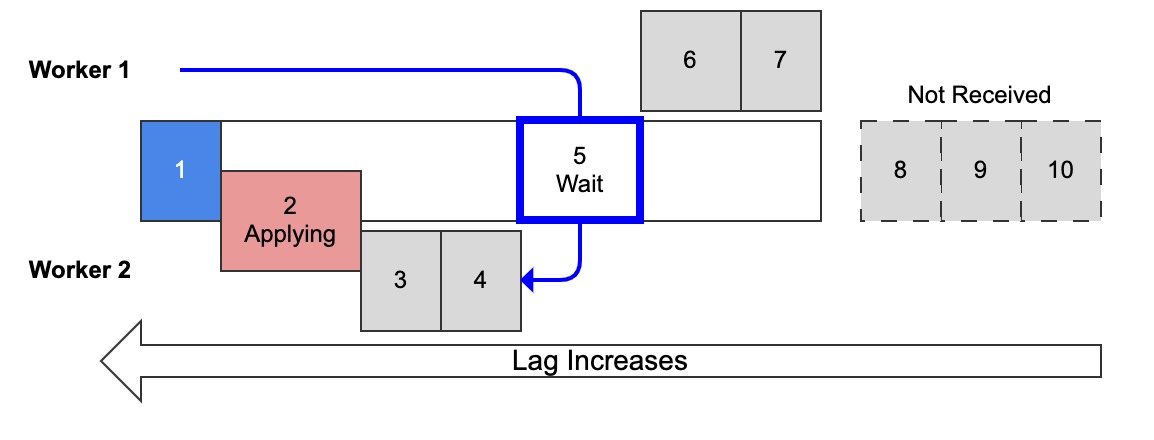

Diagram 4: Multi-threaded replication with replica preserve commit order ON, worker 1 waiting to commit

With replica_preserve_commit_order = ON, which is the default as of MySQL 8.0.27, a replica will apply transactions in parallel but commit them in order.

As a result, transaction history on the replica will be the same as the source (lag notwithstanding).

The only drawback is illustrated above in diagram 4: to preserve commit order, an applier thread might wait for other applier threads to commit preceding transactions. In this example, worker 1 has applied but not committed trx 5 because it’s waiting on worker 2 to commit trx 4. (The state of “applied but not committed” is indicated by the blue outline around trx 5.)

Normally "apply" means apply and commit, but for this section "apply" means just applying the transaction changes.

How can a trx be applied but not committed? It’s like:

BEGIN /* trx 5 */;

UPDATE t SET ... WHERE id=5;

-- Wait for RPCO

-- ...

-- ...

COMMIT;

Queries mutate data immediately in memory. Data changes aren’t made durable until the transaction commits. Until then they’re in limbo, relying on locks and undo logs for consistency and rollback. The same is true on a replica: apply immediately (as fast as possible) in memory, then commit to make durable.

On a replica, applying data changes should be more time-consuming than committing them because replica commit latency shouldn’t be an issue—presuming storage isn’t terribly slow and replica_parallel_workers isn’t absurdly large.

So if an applier thread can apply changes in parallel, then it saves time (increases replication throughput, decreases replication lag) even if it has to wait to commit.

As such, replica_preserve_commit_order = ON parallelizes the slow work (applying data changes), then serializes the fast work (committing).

This is safer—the replica is never in a state not observed on the source—but is it slower?

Performance

TL;DR: replica_preserve_commit_order = ON does not decrease replication throughput in my benchmarks.

It’s replica_parallel_workers that significantly improves performance: more workers, more throughput.†

† All the usual caveats of benchmarks apply, so real-world replicas will exhibit different performance characteristics.

Here’s how I tested the performance effects of replica preserve commit order:

- MySQL Community v8.0.30 source and replica

binlog_transaction_dependency_tracking = WRITESET- Full durability and bin logs on both

- Same machine (no network latency)

- Two tables:

fastandslow - Two tables with an auto-inc primary key and an

INTcolumn:fasthas 100,000 rows; query is a single-rowUPDATEby primary keyslowhas 2,012,000 rows; query is a 100k rangeUPDATE ... BETWEENby table scan

- 4 clients querying the

fasttable - 1 client querying the

slowtable (for 2nd run) - Slow query takes ~1.5s to execute on source, affects ~40k rows

To make reproducible runs, first initialize table data on the source, then dump the tables, then load them on the replica—same initial data.

Next, with replication stopped, execute RESET MASTER then run Finch for 60 seconds on the source to produce a single binary log with a nontrivial amount of transactions.

On the replica, reset replication (CHANGE REPLICATION SOURCE TO ...) to replay that single binary log before each run.

Constructed this way, these benchmarks measure how long it takes a replica to apply a large set of transactions from the source. It’s not measuring replication lag or transaction per second (TPS); it’s measuring replication performance in terms of runtime, so lower is better.

1st Run: Fast Transactions

The main question is: does RPCO ON make a replica slower?

Since worker threads have to wait on commit, it seems like RPCO ON would be slower, but my benchmarks don’t show that.

The first run used only the fast table and query:

Table 1: Control and runs on fast table, fast query

| Threads / RPCO | Runtime |

|---|---|

| 1 / ON | 102s (control) |

| 4 / ON | 38s |

| 4 / off | 36.6s |

| 16 / ON | 14s |

| 16 / off | 13.5s |

As a control, the first row shows single-threaded replication. As expected, a single thread takes longer than the original run, but because MySQL replication is fast it’s not dramatically longer: +42s. That’s not bad considering the source had 4x the concurrency (4 clients vs. 1 replica thread).

The remaining rows show no noticeable difference between RPCO ON or off with the same number of replica threads. With 4 threads, the difference is -1.4s (-3.7%). Although the only objectively good amount of lag is zero, an extra 1.4s doesn’t matter when a real-world replica is lagging.4

I tested with 16 threads because I thought more threads might incur more waits, but the data doesn’t support that, either.

What the data clearly shows is that replica_parallel_workers affects replication performance.

But there’s an important detail not shown: WRITESET identified huge intervals, so this workload is highly influenced by the number of worker threads because virtually none of the trx conflict.5

Without WRITESET, I wouldn’t expect a replica to exhibit performance like this.

2nd Run: Fast and Slow

The results of the first run made me think that a slow query was needed in order to block the other replica threads.

So for the second run, I added 1 client querying the slow table, running concurrently with the fast table and query (5 source clients total):

Table 2: Runs with slow table and query enabled

| Threads / RPCO | Runtime |

|---|---|

| 4 / ON | 72s |

| 4 / off | 72s |

| 8 / ON | 47s |

The slow query had the intended impact: 4 threads can’t keep up, taking 72s to apply all transactions that originally took 60s (by 5 clients) on the source.

Even though replicas are fast, examples like this demonstrate the negative impact of slow queries on replication. Before, 4 threads handled the work in almost half the time: 36.6/38s (see table 1). Now, with just 1 extra client executing a slow query, the replica can’t keep up.

Importantly, RPCO is not the reason for the slowdown: the replica took 72s with RPCO ON and off. As the last row of table 2 shows, 8 threads are needed to outpace the source; turning RPCO off won’t help.

In this context, "slow" has two meanings. On the source, the query response time is slow: about 1.5s due to the full table scan of 2M+ rows. On the replica, the trx is slow because it creates more than 40,000 row images to apply.

Interpretation

TL;DR:

- Use

replica_preserve_commit_order = ON - Use

binlog_transaction_dependency_tracking = WRITESET - Increase

replica_parallel_workersto increase replication throughput - RPCO does not affect replication throughput in benchmarks

- RPCO is unlikely to affect real-world replicas unless there’s a perfect storm of inefficiencies on the source

It’s good that enabling replica preserve commit order does not slow down replication. But it seems like it should because it funnels parallel execution into a serialized commit order queue, so what explains these results?

Short answer: the slow trx aren’t slow enough or frequent enough, and it’s difficult to make such a bad workload.

Imagine why replication would be slow due to RPCO. In theory, it would require a perfect storm: slow transactions nearly all the time such that other threads are, more often than not, waiting on the slow one before they can commit in order. But a slow transaction is presumably the result of a slow query (as in the 2nd run), so there would also need to be relatively high concurrency of the slow query on the source to make it occur in the binary logs more frequently than its response time. Moreover, the concurrent slow queries can’t conflict with each other (else they’d commit in serial on the source) or with other faster queries. If all this occurred, it should in theory cause a replica to spend more time waiting to commit than applying.

Another simpler reason why replication could be slow due to RPCO: the replica has really slow storage, making COMMIT really slow.

But in this case, it’s possible that turning RPCO off would make the situation worse by putting more load on slow storage.

Either way, RPCO would be a symptom, not the cause.

I’ve seen countless slow single-threaded replicas, but I’ve not yet seen slow MTR with WRITESET where RPCO was the cause.

Have you?

To investigate further and better, MTR metrics and instrumentation are needed.

It’d be really nice if there was a status variable like Repl_commit_order_waits, but there isn’t.

Part 3 of this series looks at what metrics and instrumentation are available, especially in terms of monitoring replication lag which, at the end of the day, is the primary objective: to keep replication lag as close to zero as possible.

On a replica, these terms are used synonymously: (SQL) thread, worker, applier. Sometimes they’re combined, like “applier thread”, to distinguish the I/O thread from the SQL applier threads. ↩︎

Relay logs can be purged because a replica will refetch the trx it needs (is missing) from the source, which could be a difference source than before a replica crash. GTIDs should always be used because they make replica recovery/rebuilding and overall replication topology recovery/reshuffling easy. ↩︎

You can force a replica to skip transactions, but don’t do it! I tell new DBAs: only skip a trx if you know why it broke and why skipping it cannot cause inconsistent data. Never skip a trx to “get replication working again”. If replication breaks and you don’t know why, it’s probably a fluke, so rebuild the replica. If the fluke keeps occurring, then you’ve got an interesting bug: dig in, figure it out, and keep rebuilding the replica until it’s fixed. ↩︎

Replication lag always matters—replication lag is data loss. What I mean is that it doesn’t matter wrt to replica performance. Even if a DBA notices that extra 1.4s, it’ll be gone before they can react to it. ↩︎

Thinking that massive parallelism was affecting the results, I did a 3rd run not describe here with much tighter row access: 8 clients querying 1,000 rows. But

WRITESETstill generated an average interval of 992 trx, and RPCO on or off still did not affect performance. ↩︎

Copyright 2025 Daniel Nichter