MySQL Password Rotation with AWS Secrets Manager and Lambda

MySQL password rotation using Amazon RDS for MySQL, AWS Secrets Manager, and AWS Lambda is a complex challenge to automate at scale. It appears easy at first—just two services and some IAM resources, right? But actual implementation quickly reveals a significant depth of considerations, choices, trade-offs, and technical problems. This page is a detailed guide to implementing MySQL 5.7 password rotation—fully automated at scale—using AWS RDS, Secrets Manager, and Lambda, and Terraform for cloud infrastructure.

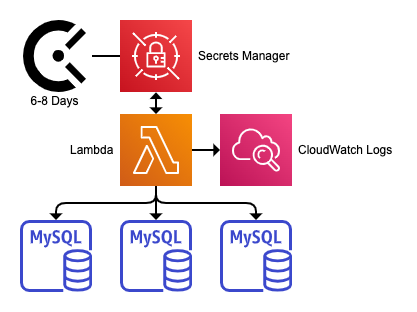

High-level Overview

AWS Services

Not shown: IAM roles and policy privileges

There are two primary services: AWS Secrets Manager and AWS Lambda. Secrets Manager stores the MySQL password and controls its rotation using a Lambda function. Lambda logs all output to AWS CloudWatch Logs. When eveything is set up and working properly, rotation happens on a fuzzy schedule starting with Secrets Manager invoking the Lambda function which connects to MySQL to change the password.

The Lambda function (“the lambda”) is not trivial. Although Secrets Manager is driving the process, the lambda is responsible for making Secrets Manager API calls to create a new pending secret, set and verify it, then swap the current and pending secrets. Read more about this: Overview of the Lambda rotation function.

Most of the work (and trouble) happens in the lambda. Although the diagram above is simple, the 13 requirements outlined in the next section reveal a gap between the simplest possible solution—which is not production-ready—and what really needs to be done and handled in the lambda to make it production-ready.

Separation of Work

The separation of work between the DBA team and app developers motivates several requirements and design choices:

Your environment, teams, and separation of work may be different. But for the purposes of this page, we have one DBA team and many app teams/developers. The DBA team creates, maintains, and distributes a version-controlled Terraform module which creates properly configured RDS instances. App developers (on various, unrelated teams) use this module in their application’s infrastructure code (“infra code”) to create AWS resources. The DBA team maintains a backend service which does various post-provision tasks. For the DBA team, this separation enables operations at scale because the Terraform module stamps out consistently-made RDS instance—no bespoke infrastructure. For app developers, it allows self-service database provisioning (and decommissioning), ease-of-use, and scale.

This separation requires a fair amount of complex work by the DBA team. It’s not easy. The password rotation lambda alone is quite complicated, which is why this page is a long read. By the end, you will understand the issues this separation creates and how to solve them. The benefits exceed the costs: once a separation like this is achieved, both the DBA team and app developers are unblocked, able to provision and operate thousands of RDS instances with relative ease.

Default Password Rotation Lambda

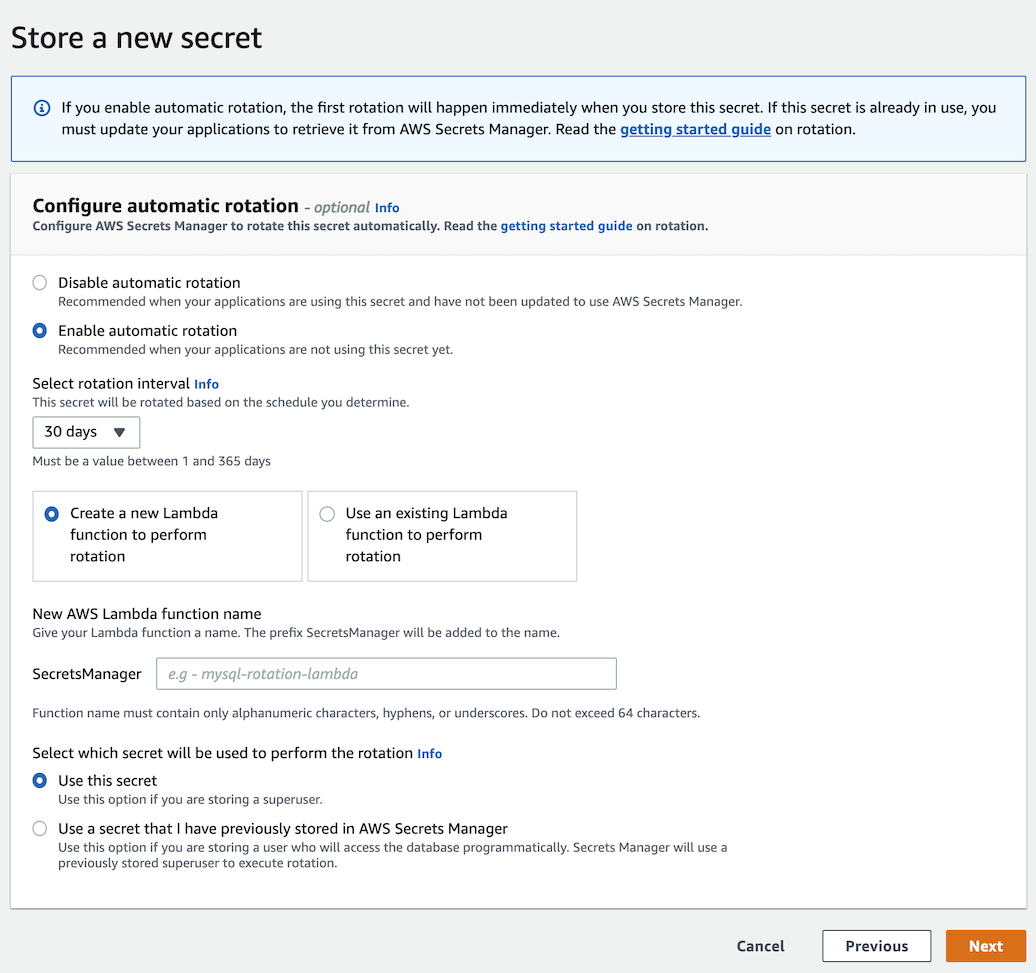

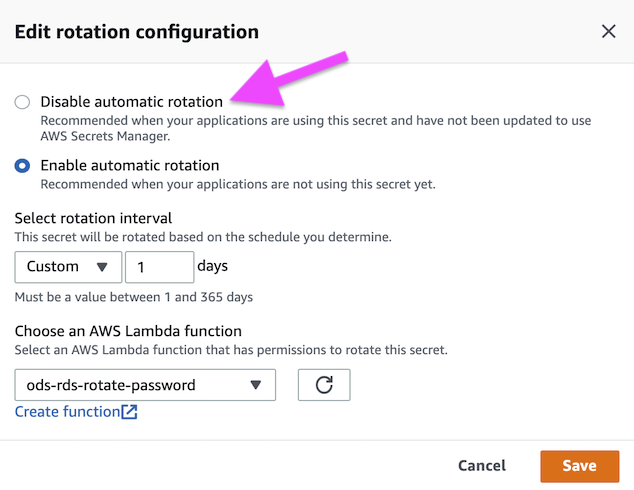

A quick note on using the default AWS password rotation lambda. In the AWS console, when creating a new secret and enabling rotation, it prompts you to create a new lambda or using an existing one:

I tried this and it does not work. For one thing, it doesn’t meet requiremnt 5: TLS connections required. (This is an outstanding issue: aws-samples/aws-secrets-manager-rotation-lambdas issue #14.) It’s also not automated, not unit tested, and doesn’t rotate in parallel, retry, or rollback. The latter (rollback) is particularly important because not removing an unused AWSPENDING staging label blocks future Secrets Manager rotations.

As far as I can tell, the default AWS password rotation lambda only works in the simplest case when other resources are also set up in the simplest case. It’s not a secure and robust solution for production.

Requirements

1. Rotate MySQL 5.7 passwords

MySQL 8 supports dual passwords, which makes password rotation a little easier. But we’re running MySQL 5.7 which has only a single password per user. That makes handling password rotation more difficult for the application, which we’ll look at later.

Supporting MySQL 8 is not a goal.

2. Same user, single password rotation

There are several methods for rotating a MySQL user password:

| Same User | Root User |

|---|---|

| Single Password | Single Password |

| Dual Password | Dual Password |

| Multi-user |

First choice is whether we use the same user (i.e. the user whose password is being rotated) or a root user. I prefer same user to avoid having more root users than necessary. Also, root user has no benefits unless using multi-user. I prefer not using multi-users to avoid having more users than necessary.

Same user, single password means the password rotation lambda (PRL) will connect to MySQL as the user whose password is being rotated and execute ALTER USER CURRENT_USER IDENTIFIED BY '<newpass>'. That is the simplest, most direct approach.

PRL = Password Rotation Lambda, the code that runs in AWS Lambda to rotate a MySQL user password

3. Zero knowledge passwords

Normally, DBAs would have access to all MySQL user passwords. But it’s more secure if they don’t. This is possible given the separation of work. One detail not mentioned there: application teams have their own AWS accounts to which the DBA team does not have access. This works because the DBA team only provides a Terraform module that app teams use to run infra code which makes AWS resources in their AWS accounts. Consequently, we can limit secret access only to the PRL, the app, and the app developers (who are admins of their AWS account).

How this works will become clear by the end of this page. The salient point and requirement is: only the PRL, the app, and the app developers can access MySQL passwords stored in Secrets Manager. Everything and everyone else, including the DBA team, has zero knowledge of the passwords.

4. Run in VPC

All resources must exist in a VPC. Nothing is on a public network or has public IPs. This means the PRL needs a special setup: Configuring a Lambda function to access resources in a VPC. AWS resources in a VPC generally require more work, which is why we make this requirement explicit.

5. TLS connections required

Even though running in a VPC, we require TLS for all connections: to MySQL and to all AWS APIs. This is important because the PRL will query public AWS APIs (we can route from VPC to public internet but not the reverse).

In the cloud, we should use TLS connections for all APIs. Even VPC endpoints will use TLS connections.

6. One password per user

Each AWS account represents one application, so all RDS instances in the account are used by the one, same application. If there are multiple RDS instances, it’s because the application has sharded, so all database instances are one logical database. Therefore, the MySQL user on each database instance is also logically the same and has the same password stored in one secret.

If access controls to secrets are the same, then different passwords for each database instance is not more secure because compromising one secret (i.e. defeating the access controls) compromises all the secrets. Using different passwords guards against leaked password, but frequent password rotation also guards against leaked passwords. Therefore, different passwords is not a requirement.

7. Parallel rotations

The PRL must rotate passwords in parallel, up to some limit. In the first diagram at the top of this page, the PRL rotates the password on all 3 MySQL instances in parallel. This reduces the time that the application’s access to MySQL is split between two passwords.

8. Retry and rollback

With three systems (RDS/MySQL, Lambda, and Secrets Manager), something will fail eventually. When it does, the PRL must retry to ensure the failure isn’t a blip (a transient failure), and if retrying fails it must roll back.

The PRL must roll back if any database instance fails to rotate after all retries. For example, if we have 3 database instances and the first two rotate but the third fails, we must roll back the first two so that all databases are in sync with respect to the MySQL user password. Else, the application will only work on 2 of 3 database instances, which can be worse than working on zero of them because partial success can be confusing to debug. If the application developers see 66% success (2/3 rotated successfully), they might think the database is fine and the problem is elsewhere. We prioritize application access over password rotation.

If the rollback fails too, then we’re really in a pickle. A human will have to figure out what went terribly wrong and fix it manually. This double failure should be incredibly rare.

9. Handle secrets in limbo

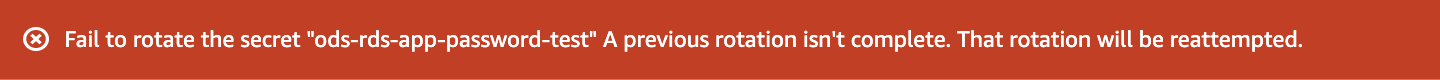

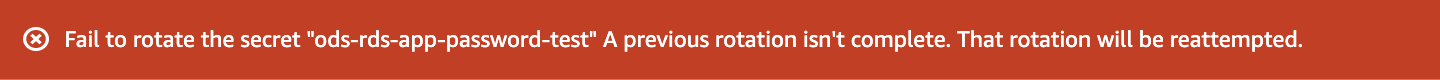

The first step of a Secrets Manager rotation is creating a secret with the AWSPENDING staging label. On failure, the PRL should rollback/remove the pending secret, but other failures (e.g. the PRL panics) could cause the pending secret to be left. This blocks future Secrets Manager rotations; the AWS console returns a cryptic and misleading error:

Later, we’ll look at this error in more detail. The requirement is that the PRL handles secrets in limbo, essentially fixing previous broken rotations.

10. Manually invoked rotation

The primary use case of the PRL is being invoked automatically by Secrets Manager. When everything is stable and working, this is the autopilot mode working quietly in the background. But there is an additional use case: adding new database instances. In this case, we should not rotate secrets by calling Secrets Manager because it would needlessly rotate secrets for all existing databases. That’s not terrible if the application handles password rotation with ease, but it’s unnecessary so we avoid it. Instead, we should manually invoke the PRL to set the MySQL user password, on new database instances, to the current secret value (password). This requirement will become more clear when technical problems Default Provision Password (DPP) and Initial Password Rotation (IPR) are addressed.

Moreover, from experience I can tell you that adding custom functionality to the PRL is very helpful. For example, the ability to verify the MySQL user connection is super helpful: the PRL simply tries to connect to MySQL with the current password. This lets the DBA team verify the secret since they don’t have access to the secret or the application.

11. Code unit tests

The PRL function code should be unit tested as best as possible. This is quite difficult because our personal computers can’t run the PRL in the same way or environment as AWS. It’d be great if AWS published a Docker container that simulated the AWS Lambda service. For a PRL invoked by Secrets Manager this becomes even more complicated unless you simulate how Secrets Manager invokes the Lambda and handles success and failure.

How does Secrets Manager handle failure? I have never seen this documented. By direct observation, we see that Secrets Manager tries 5 times with a 100 second wait between tries. On final failure, it simply stops trying. It does not notify or log final failure.

All that aside, though, the PRL should be unit tested as best as possible because it’s important code that, when it fails, has the potential to break the app and cause an outage.

12. Thorough logging and debug

From previous requirements you can see why thorough logging is required: a lot is happening, which means a lot can break. Without thorough logs, it’s nearly impossible to debug a PRL. By default, Lambda output logs to CloudWach Logs, which is sufficient to start.

Closely related is having a debug mode or level of logging. When necessary, we need to see everything the PRL is doing. When enabled, the PRL should log so verbosely that we’re sure to see any problem or bug. This was a lifesaver for me in the early days of PRL development.

13. Fully Automated

The entire PRL setup must be fully automated, which means no engineer manually creates any resource or enters any value. As seen in Separation of Work, the DBA team publishes a ready-made Terraform module that app developers use to create all the necessary AWS resources. Also, the DBA team has a backend service which does post-provision (i.e. post-Terraform) tasks.

Fully automating the PRL is a lot more difficult but worth the investment.

Technical Problems and Solutions

Failed Rotation and Staging Labels

Failed rotations can block future Secrets Manager rotations. The problem is the staging labels: AWSCURRENT, AWSPENDING, and AWSPREVIOUS. Secrets Manager uses these to track different versions of the secret during rotation. When the PRL fails, Secrets Manager is left in a broken state if the staging labels are not reset to normal. If you try to rotate the secret again, the AWS console shows an unhelpful error message:

Excuse me while I digress to point out why that error message is unhelpful:

- It does not say or give any clue as to why it failed.

- It does not say where to look to see the failure.

- It says “Fail” but also “isn’t completed”—are those the same?

- Which “previous rotation”?

- How often will the “previous rotation” be reattempted?

- You cannot see or cancel the “previous rotation” in the AWS console.

In essence, the error message says only, “This rotation didn’t work because some previous rotation didn’t work.”

First, let’s see the normal state of staging labels using the command line aws secretsmanager describe-secret:

{

"ARN": "arn:aws:secretsmanager:us-west-2:123456789012:secret:mysql-user-password-X7ax21",

"Name": "mysql-user-password",

"Description": "Rotates the MySQL user password",

"RotationEnabled": true,

"RotationLambdaARN": "arn:aws:lambda:us-west-2:123456789012:function:mysql-password-rotation",

"RotationRules": {

"AutomaticallyAfterDays": 1

},

"LastRotatedDate": "2020-11-03T13:35:51.599000-05:00",

"LastChangedDate": "2020-11-03T13:35:51.607000-05:00",

"LastAccessedDate": "2020-11-02T19:00:00-05:00",

"Tags": [],

"VersionIdsToStages": {

"0e402657-8ed6-4ea4-b908-4dadc09e5928": [

"AWSCURRENT"

],

"4bacb6fe-4753-4928-09ac-364f51b7cc0b": [

"AWSPREVIOUS"

]

}

}

The normal state of staging labels is having only AWSCURRENT and AWSPREVIOUS, as shown above. During rotation, the new secret version has the AWSPENDING staging label:

{

/* Other output removed */

"VersionIdsToStages": {

"0e402657-8ed6-4ea4-b908-4dadc09e5928": [

"AWSCURRENT"

],

"4bacb6fe-4753-4928-09ac-364f51b7cc0b": [

"AWSPREVIOUS"

],

"b862db6d-8b73-4fc8-bee8-2edd74a9a527": [ /*

"AWSPENDING" * New secret

] */

}

}

If rotation fails and does not remove the AWSPENDING version of the secret, Secrets Manager will show the unhelpful error message above.

Solution

Requirement 9, Handle secrets in limbo, addresses this problem. The PRL must check for and use the pending secret (the secret with the AWSPENDING staging label) if its version ID matches the client request token from Secrets Manager. (This is an implementation detail that you can read about in the Lambda rotation function docs.) In short, it means that the PRL must reuse its own pending secrets.

Or, you can manually delete the AWSPENDING version:

aws secretsmanager update-secret-version-stage \

--secret-id mysql-user-password \

--version-stage AWSPENDING \

--remove-from-version-id b862db6d-8b73-4fc8-bee8-2edd74a9a527

DO NOT use aws secretsmanager cancel-rotate-secret to fix this! I read the fine manual, but I also get busy and make some educated guesses about what a command does based on its name, so I thought cancel-rotate-secret would cancel “A previous rotation” but no: cancel-rotate-secret disables secret rotation, i.e. automatic rotation every N days. Like the AWS console, this command would be better named disable-automatic-rotation:

You cannot see secret versions/staging labels in the AWS console. When this problem occurs, you must use the AWS CLI or your own code calling the Secrets Manager API.

Manually Invoke Lambda

The PRL is a generic Lambda function. We use it for password rotation, but we can also program it to do other things. Secrets Manager does not use Lambda in a special way, it’s merely a client that invokes the PRL in a prescribed four-step process: Overview of the Lambda rotation function. In practice, you will need to bypass Secrets Manager and invoke the password rotation lambda directly to:

- Verify current password: verify PRL can connect to Secrets Manager and MySQL using the current password

- Set current password: don’t rotate password, just set MySQL user password to its current value

- Get PRL code version: the actual code version, not the Lambda version

- Do other things: you may have needs specific to your infrastructure

Like Secrets Manager, you and other systems will be clients that invoke the PRL. For example, verifying the current password is really helpful to ensure the PRL itself (apart from Secrets Manager) is working. You will find that you and others systems need to bypass Secrets Manager and invoke the lambda directly.

Solution

The lambda function code must distinguish between invocations by Secrets Manager and manual invocations by other clients. This is pretty easy:

// InvokedBySecretsManager returns true if the event is from Secrets Manager.

func InvokedBySecretsManager(event map[string]string) bool {

_, haveToken := event["ClientRequestToken"]

_, haveSecretId := event["SecretId"]

_, haveStep := event["Step"]

return haveToken && haveSecretId && haveStep

}

As that Go function shows, the event from a Secrets Manager invocation has three fields: ClientRequestToken, SecretId, and Step. If all three fields are set, it’s an invocation by Secrets Manager (or a unit test pretending to be Secrets Manager). Else, the event should be handled as a manual invocation and everything in the event is your choice, as well as the return.

This distinction is made in the lambda handler function, and Lambda itself does not know or care. In fact, Lambda has no special awareness of Secrets Manager; as previously stated, Secrets Manager is simply one client that invokes the PRL in a prescribed four-step process.

You can do anything inside your manual invocation handler code. You should develop conventions for the expected input and output. For example, the code snippet below returns the PRL function code version when event contains a version field:

const VERSION = "1.0.0"

var SHA = "" // set on build

func (r rotatePassword) Handler(ctx context.Context, event map[string]string) (map[string]string, error) {

// Return version and SHA if event[version] is set

if _, ok := event["version"]; ok {

ret := map[string]string{

"prl-version": VERSION,

"prl-sha": SHA,

}

return ret, nil

}

The client receives a JSON document like:

{

"prl-version": "1.0.0",

"prl-sha": "70d89cfcae18c2845e1f693aa053da394a873578"

}

To manually invoke the PRL and get that version response:

aws lambda invoke \

--function-name arn:aws:lambda:us-east-1:123456789012:function:mysql-password-rotation \

--invocation-type RequestResponse \

--payload "$(echo '{"version":1}' | base64)" \

response.json

The --payload becomes the input event. The output is printed to response.json (for some reason, the AWS CLI requires an output file for this command, it won’t print to STDOUT).

Code to handle manual invocation is separate from code to handle Secrets Manager invocation. Handling manual invocation is in addition to handling the four steps of Secrets Manager rotation.

Lambda Concurrency

Lambda functions run concurrently by default. For truly stateless processing (for example, using a Lambda to process images is truly stateless if the images are unrelated), reasoning about and programming the Lambda function is easier. But a password rotation lambda serves a stateful process, a tiny state machine: the four-step rotation executed by Secrets Manager. More importantly, there is no affinity which means, for any given rotation, each step can (and often does) execute on a different instance of the PRL.

The diagram above shows 3 concurrent instances of the same PRL (i.e. it’s the same Lambda function; AWS is running 3 instances of it in parallel). If three different secrets are rotated at the same time, each rotation step executed by Secrets Manager can occur on a different PRL instance. Each rotation happens in order but not on the same PRL instance and not sequentially. For example, rotation 1 step 4 happens last even though it started at the same time as the other two rotations.

Solution

Concurrency can be disabled by setting reserved concurrency on the function to 1, but you should not do this. I suggest setting reserved concurrency for the PRL equal to the number of secrets it rotates. For example, if the same PRL rotates 5 secrets, then set reserved concurrency to 5. If it only rotates 1 secret, then set reserved concurrency to 2 minimum to ensure the PRL handles concurrency.

With respect to the lambda function code, each Secrets Manager step must be treated as a completely new process. For example, on a Linux command line you can imagine running each step by running program prl four times on four different hosts:

$ ssh host1 "prl 1" && \

ssh host2 "prl 2" && \

ssh host3 "prl 3" && \

ssh host4 "prl 4"

The && ensures that step 2 only runs if step 1 exits zero, and step 3 only runs if step 2 exits zero, and step 4 only runs if step 3 exits zero. Even though all four steps run on different hosts, they always run in order.

I do not advise caching anything in the PRL; but if you do, you must handle cache expiration because, for example, in the diagram above rotation 1 starts on PRL 1 but ends on PRL 3. If PRL 1 caches anything about rotation 1, how will it know when to expire the cache?

Testing

Testing an AWS Lambda, like any cloud resource, is not easy because we cannot reproduce the full cloud environment outside of the cloud. We can simulate many parts of the cloud, but simulating all is probably not possible. Consider how many AWS services and resources are used to run a Lambda function: IAM (roles, policies), security group, VPC (subnets, routing, etc.), CloudWatch, etc.

Solution

The solution to testing in this situation is separation of concerns:

| Concern | Code Handles |

|---|---|

| Your environment | AWS access/credentials/sessions, proxies, auth, deploy/runtime |

| Your manual invocation | See Manually Invoke Lambda |

| Lambda integration | Basic low-level hook into AWS Lambda |

| Secrets Manager invocation | Four rotation steps of Secrets Manager |

| Database password rotation | Set MySQL user password |

I wrote an open-source database password rotation lambda for AWS: square/password-rotation-lambda. Let’s call this the “PRL package” because it’s a Go package. The PRL package handles the bottom 3 concerns: Lambda integration, Secrets Manager invocation, and database password rotation. Best of all: it’s tested. This means your code only handles your concerns (the top 2): your environment and your manual invocation. You can read the PRL package docs to see how it’s used, but point is: all the important low-level unit testing is done for you by square/password-rotation-lambda.

Even if you don’t use this PRL package, it demonstrates how to separate these concerns and test them.

Default Provision Password (DPP)

We need a first password for the MySQL user. I call this the “default provision password” (DPP) for reasons that will be clear by the end of this section. Ultimately, the MySQL user password will be set to the secret value. The problem is getting the two in sync.

If everything could be done in infra code, there wouldn’t be a problem. On provision, starting with no AWS resources, the infra code would:

- Create the PRL and the secrets

- Enable rotation on the secrets which causes the initial password rotation

- Initial password rotation stores a random password in the secrets

- Create database instances

- Create MySQL users using the random passwords

In theory, that should work. But in our case, given the separation of work, there are a few problems:

(1) The DBA team provides a Terrafom module to app developers. This module can provision N-many identical database instances (varying by identifier) using for_each, like:

resource "aws_db_instance" "rds-mysql" {

for_each = var.db_instances

identifier = each.key

}

This is ideal for app developers: they can easily create many aws_db_instance with the same configuration. But the problem is that Terraform cannot use for_each in a provider, so the module cannot connect to the list of RDS instances because each needs its own MySQL provider. Even if that worked, there’s another problem…

(2) The MySQL provider has a tls option, but it only enables TLS. To make a TLS connection to RDS, you must load the RDS root certificate, but the MySQL provider source code does not show any way of doing this. Since we always required TLS connection, this is a blocker.

(3) Even if (1) and (2) could be solved, I do not advise putting MySQL users and privileges in infrastructure code. Instead, a trusted backend service should create MySQL users and grant them privileges. This allows a single source of truth and auditing, which are critical for maximum security. It also decouples MySQL users and privileges from infrastructure, which is good because they are independent. By contrast, having infra code create MySQL users and grant them privileges runs the risk of drift: MySQL users and privileges change as different versions of infra code are deployed (semver the infra code). Inconsistency is the bane of security and operations. Also, access to infra code might be more permissive than access to MySQL users and privileges should be.

(4) Could the DBA team write the module differently to work around these problems? Not really. If the module did not accept a list of RDS instances to create and, instead, created only a single instance, if an app team wanted 4 instances they would have to declare the module 4 times, but this doesn’t work either because the majority of the module is common infrastructure (security group, db subnet group, db parameter group, etc.) which would create 4 duplicates. The DBA team would have to provide one module for common infrastructure and another module for database instances. That might work, but it still doesn’t solve (1) or (2) unless the app team also declares 4 MySQL providers—but now we’re not solving or simplifying problems, we’re just trading one set of problems for another.

A single Terraform module that creates N-many database instances is the best experience for app developers. These problems are implementation details that the DBA team needs to handle and hide from app teams.

Solution

Since infra code cannot set the first password for MySQL users, the DBA team’s backend service must set them post-provision (after infra code has run). This is advisable in any case for the reasons stated above in (3). And since initial password rotation happens before the backend service runs, the backend service cannot create MySQL users with the random passwords because of the zero knowledge passwords requirement.

The infra code should not transmit the random passwords to the backend service. Never transmit passwords if avoidable.

With a default provision password (DPP) and the ability to manually invoke the PRL, the solution is easy. When the backend service runs post-provision, it creates MySQL users with the DPP. (The DPP can be any value, even an empty string.) The PRL is also hard-coded to use the DPP when manually invoked to do an “application password reset” (APR): a feature which connects to a database instance using the DPP and resets the MySQL user password to the current secret value (the random password).

APR = Application Password Reset, a PRL manual invoke feature to reset MySQL password from DPP to current secret value

A hard-coded password is a bad idea, and the DPP is no exception but it is an acceptable trade-off given the extremely unlikely worst-case scenario which is: a bad actor gains access using the DPP. A window of vulnerability is open for several milliseconds: between CREATE USER IDENTIFIED BY 'DPP' REQUIRE SSL and APR. To exploit that window, a bad actor would need to have already comprised internal systems and left spyware to wait for new RDS instances, then wait for the MySQL users to be created and connect—within a few milliseconds—before the APR completes. If a bad actor can do that, it’s probably game over. If that is not an acceptable risk/solution trade-off, then reboot the RDS instance after APR to disconnect any bad actors. They can only regain access if they have access to Secrets Manager to get the random password. If a bad actor can do that, then it’s definitely game over.

Initial Password Rotation (IPR)

Enabling password rotation on a secret rotates the secret—the initial password rotation (IPR). For example, the AWS console notes:

IPR is a challenge with automation because we must consider whether the RDS instances are created before, after, or during the creation of the PRL:

- Before (RDS → PRL): If RDS instances are created before the PRL, are the MySQL users also created before?

- If yes, then a DPP is needed for IPR to work because the PRL connects with the current password. However, this requires infra code to create MySQL users which does not work, as discussed above in Default Provision Password.

- If no, then the PRL will fail (because the MySQL users don’t exist) and roll back which means IPR fails—the initial password is not rotated.

- After (PRL → RDS): If there are no database instances, the PRL has nothing to do which it can treat as success. The secret value is changed even though no MySQL passwords were changed.

- During: Creating RDS instances and the PRL at the same time is the most difficult case because the PRL may or may not see or have access to the new databases. This amounts to a race condition, so best to avoid it altogether.

Solution

The “After” approach works. First create the PRL. Then create the secrets and eanble rotation, which triggers the IPR. Third, wait about 20 seconds because PRL invocation is asynchronous, so a wait is a crude but effective strategy to give the PRL time to run before any RDS instances are created. With no instances, the IPR happens almost immediately. (Which makes it a no-op password rotation since no MySQL passwords actually change, the PRL just sets new secret values.) Lastly, create RDS instances.

DPP and IPR work together. The latter (IPR) happens only in infra code. End result is that new secrets immediately have random passwords. The former (DPP) happens post-provision in the DBA team’s backend service. End result is that APR resets MySQL user passwords from DPP to the random passwords set by IPR.

Deleted Secrets Are Kept and Hidden

Secrets are not deleted immediately, they are kept for a configurable recovery window. With fully automated infrastructure, this creates a problem when deleting and recreating secrets with the same names: it fails because the secrets already exist (but deleted).

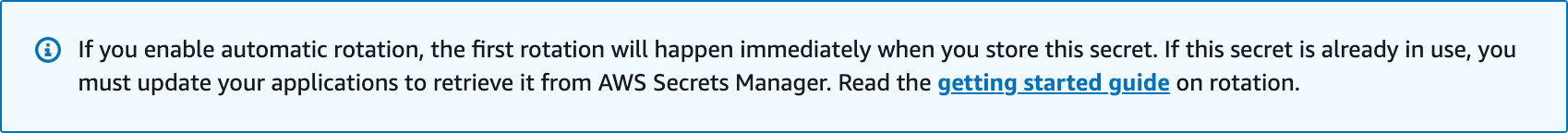

To see deleted secrets in the AWS console, click the gear icon (in Secrets Manager) to open the preferences, then enable “Show secrets scheduled for deletion” and “Deleted on”, as shown below.

You can select a deleted secret and restore it.

Solution

Secret names could be dynamic; for example, append the date to the secret name. I don’t like this solution because secret names are used in other places, notably IAM policies, so dynamic names makes everything more difficult because the names have to be stored and passed where needed. For example, if we provision a database today the secret name would be secret-20201213, and tomorrow secret-20201214, and next month secret-20210101. That means for any given database you don’t know the secret name, you have to look it up. And if the application grows over time, adding more databases, each will have a different secret name even though all databases are logically the same (for the same app). For operations at scale, this kind of variably adds no value, it only complicates ops for both human and machine.

Static secret names are better. They really simplify operations and IAM policies. Plus, rebuilding cloud infrastructure is the exception not the norm. After deleting statically-named secrets, there are two solutions to immediately recreate them with Terraform. After Terraform destroys the secrets, use aws secretsmanager delete-secret --force-delete-without-recovery to immediately delete secrets. (Actually, it takes several seconds.) This lets Terraform recreate the secrets. Alternatively, you can restore secrets in the AWS console (cancel the deletion), then terraform import the restored secrets. This lets Terraform reuse the secrets.

MySQL Driver

No MySQL driver natively supports password rotation, which means that all database connections are lost when the password is rotated, and the connections are not recovered until the application is restarted which reloads the database credentials (or DSN). By “connections are lost” I mean that connections will eventually reconnect and encounter MySQL error 1045: access denied. For production apps that cannot take downtime, this is unacceptable. Even if the app developers coordinate password rotation with a rolling app restart, downtime is limited to how fast the app can restart.

Once a MySQL connection is authenticated, it remains valid until disconnected or FLUSH PRIVILEGES is executed. Therefore, connecitons are not immediatley lost when the password changes. The impact of password rotation depends on how the MySQL driver connection pool is configured. If the pool is large and allows many long-lived idle connections, then password rotation may have little effect. But if the pool is small and limits idle connections, then password rotation can have a greater, more immediate effect.

Solution

MySQL 8.0 has dual password support. But the requirement is password rotation with MySQL 5.7. The same solution applies to MySQL 5.6, but do not use 5.6 because it is end of life (EOL) February, 2021.

I wrote go-mysql/hotswap-dsn-driver to solve this problem for Go. The solution is very simple: on MySQL error 1045 (access denied), a user-provided function is called to reload the DSN. For this context, that user-provided function will call Secrets Manager to get the current secret value that the PRL just rotated and saved. Of course, this is thread-safe (or “safe for use by multiple goroutines”, in Go parlance). The result is zero downtime, only a ~100 millisecond delay on new database connections.

Even if you don’t use Go, it demonstrates how to handle password rotation in a MySQL driver. I hope someone does the same for other major languages.

Terraform

Implementing a password rotation lambda in Terraform (TF) that meets all requirements and solves all technical problems is not terribly complicated. There are three parts to the infrastructure code: IAM roles and policies, the Lambda function itself, and the Secrets Manager secrets.

This page does not explain how to set up or use Terraform. Please read the Terraform Documentation.

The examples below are not a complete, working infrastructure. You will need more infra code to set up additional resources, like the RDS instances.

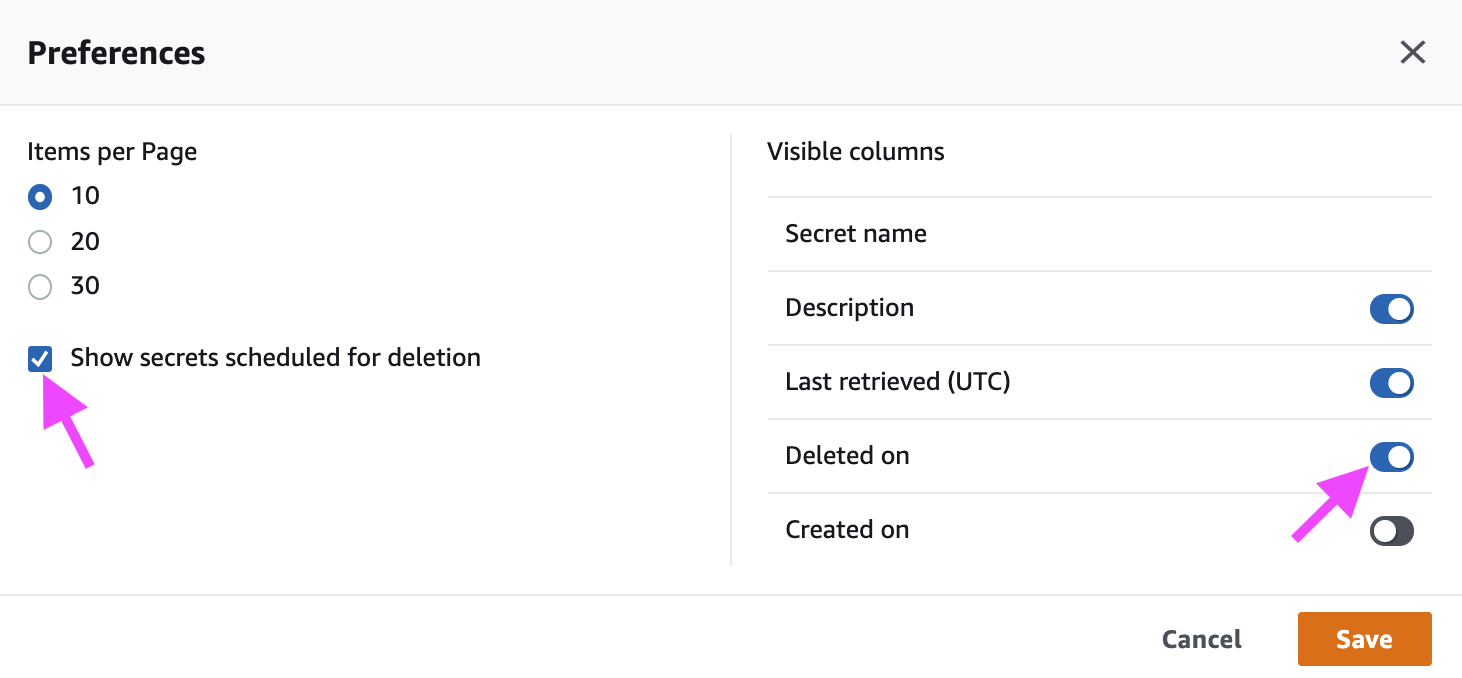

IAM Role and Policies

First we need to create an IAM role and policy for the PRL. Read the comments in the Terraform code below for more details.

# Trust policy: allow AWS Lambda service to assume this role while running the lambda.

# https://docs.aws.amazon.com/lambda/latest/dg/lambda-permissions.html

data "aws_iam_policy_document" "prl-trust" {

statement {

sid = "TrustLambda"

actions = ["sts:AssumeRole"]

principals {

type = "Service"

identifiers = ["lambda.amazonaws.com"]

}

}

}

# Execution role: the role the PRL uses when running (invoked).

# This role must have policies (defined next) to allow the lambda

# to do and access everything it needs.

resource "aws_iam_role" "prl-role" {

name = "mysql-password-rotation-lambda"

assume_role_policy = data.aws_iam_policy_document.prl-trust.json

}

# Execution policy: execution role permissions. These vary depending

# on what the PRL does. The permissions below should be the minimum

# requirements.

data "aws_iam_policy_document" "prl-policy" {

# PRL queries RDS API to automatically discovers all RDS instances

# in the same AWS account.

statement {

actions = ["rds:DescribeDBInstances"]

resources = ["*"]

}

# PRL function code is loaded from an S3 bucket. We create and

# upload function.zip (which contains the function code Go binary).

statement {

actions = ["s3:GetObject"]

resources = ["arn:aws:s3:::prl-func/function.zip"]

}

# PRL reads and writes secrets which contain MySQL user passwords.

# The condition allows Secrets Manager to use the PRL.

statement {

actions = [

"secretsmanager:DescribeSecret",

"secretsmanager:GetSecretValue",

"secretsmanager:PutSecretValue",

"secretsmanager:UpdateSecretVersionStage",

]

resources = ["*"]

condition {

test = "StringLike"

variable = "secretsmanager:resource/AllowRotationLambdaArn"

values = ["arn:aws:lambda:*:123456789012:function:mysql-password-rotation"]

}

}

}

# Attach execution policy as inline policy to execution role.

# Use an inline policy, not a customer-managed policy, because

# the policy is unique and specific to the PRL. No other IAM

# entities should use this policy.

resource "aws_iam_role_policy" "prl" {

name = "lambda-exec"

role = aws_iam_role.prl-role.id

policy = data.aws_iam_policy_document.prl-policy.json

}

# PRL runs in VPC which requires the AWS-managed AWSLambdaVPCAccessExecutionRole

# role. Attach it to the execution role. If the PRL needs other

# AWS-managed roles, you can add them to the for_each list.

resource "aws_iam_role_policy_attachment" "lambda-exec" {

for_each = {

vpc = "arn:aws:iam::aws:policy/service-role/AWSLambdaVPCAccessExecutionRole"

}

role = aws_iam_role.prl-role.id

policy_arn = each.value

}

AWS account 123456789012 is fake. Be sure to replace it with your AWS account number.

The IAM policy references S3 bucket name "prl-func" which is created later. The name must be changed in all Terraform code because S3 bucket names are globally unique.

Once this TF code is applied, you should see the mysql-password-rotation-lambda IAM role and inline policy in the AWS console:

Lambda Function

First, let’s create the Lambda function code (using Go) and an S3 bucket to hold it. After, we’ll write the TF code to create the PRL using the function code stored in the S3 bucket.

Function Code and S3 Bucket

Create an S3 bucket to hold the function code which we’ll upload as function.zip. Be mindful of the S3 bucket access policy: Terraform needs access from wherever and however you run it. If all AWS resources are in the same account, access should not be an issue. But in this setup (i.e. given the separation of work), the S3 bucket is in the DBA team’s AWS account because, like the TF module they provide, they also provide the PRL function code. So the S3 bucket in the DBA team’s AWS account needs an access policy to allow and restrict cross-account access only from other AWS accounts in the same AWS organization. S3 access policies are beyond the scope of this page, but you probably want a condition like:

"Condition": {

"StringEquals": {

"aws:PrincipalOrgID": "o-IamNotReal"

}

}

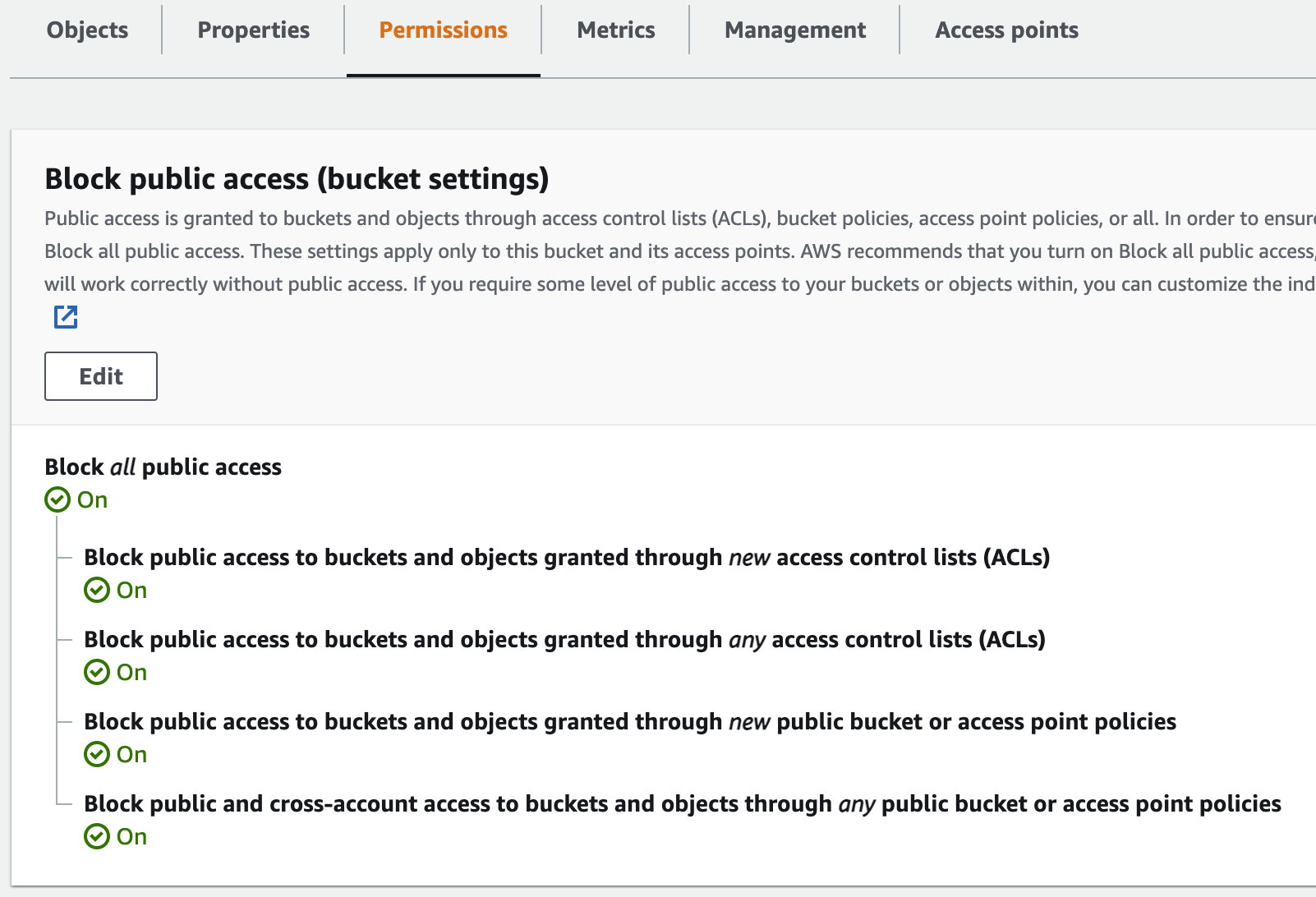

Be sure the S3 bucket blocks all public access!

Be sure the S3 bucket blocks all public access!

Seriously, don’t let your PRL becomes a news story about how public access lead to being hacked. Granted, the PRL code is pretty harmless by itself, but don’t take the risk when it’s so easy to avoid completely. In the AWS console, the list of S3 buckets must say:

And when viewing the bucket permissions, it must say:

Using an S3 access point would be better, but as far as I can tell TF does not work with S3 access points (I could be wrong about this).

Be sure to create the bucket in the same AWS region as other resources. For this example, let’s call the bucket prl-func, so its ARN is arn:aws:s3:::prl-func.

S3 bucket names are globally unique, so you must change "prl-func" in all Terraform code.

Function Code

Lucky you: square/password-rotation-lambda has a ready-made working example in examples/rds. Clone the repo, change to that directory, build the PRL binary for Linux, and put it in a zip file:

$ GOOS=linux GOARCH=amd64 go build -o prl-bin

$ zip function.zip prl-bin

Upload function.zip to the S3 bucket.

Alternatively, here is a more complex example using an HTTP proxy for the RDS API, a VPC endpoint for the Secrets Manager API, and a custom SecretSetter implementation (MyRandomPassword) to handle manual invocation:

package main

import (

"context"

"encoding/json"

"fmt"

"log"

"net/http"

"net/url"

"os"

"time"

"github.com/aws/aws-lambda-go/lambda"

"github.com/aws/aws-sdk-go/aws"

"github.com/aws/aws-sdk-go/aws/session"

"github.com/aws/aws-sdk-go/service/rds"

"github.com/aws/aws-sdk-go/service/secretsmanager"

"github.com/square/password-rotation-lambda/v2"

"github.com/square/password-rotation-lambda/v2/db"

"github.com/square/password-rotation-lambda/v2/db/mysql"

)

const VERSION = "v1.0.0"

var SHA = ""

var (

parallel = uint(10)

retries = uint(2)

retryWait = time.Duration(2 * time.Second)

)

func init() {

rotate.Debug = os.Getenv("DEBUG") == "yes"

}

func main() {

log.Printf("prl-bin %s (%s)", VERSION, SHA)

// Get proxy URL from env var and create *http.Client using it

proxyURL, err := url.Parse(os.Getenv("HTTPS_PROXY"))

if err != nil {

log.Fatalf("error parsing HTTPS_PROXY: %s", err)

}

proxyClient := &http.Client{

Timeout: time.Duration(5 * time.Second),

Transport: &http.Transport{Proxy: http.ProxyURL(proxyURL)},

}

// Make AWS session for RDS API via proxy

rdsSess, err := session.NewSession(&aws.Config{

MaxRetries: aws.Int(2),

HTTPClient: proxyClient,

})

if err != nil {

log.Fatalf("error making AWS session for RDS: %s", err)

}

// Make MySQL password setter to handle changing MySQL user password

ps := mysql.NewPasswordSetter(mysql.Config{

RDSClient: rds.New(rdsSess), // RDS API client

DbClient: mysql.NewRDSClient(true, false), // RDS MySQL cilent (true=TLS, false=dry run)

Parallel: parallel, // rotate password on 10 RDS concurrently

Retry: retries, // 5 tries total

RetryWait: retryWait, // sleep between tries

})

// Make AWS session for Secrets Manager via VPC endpoint

smSess, err := session.NewSession(&aws.Config{

MaxRetries: aws.Int(2),

Endpoint: aws.String("..."), // using VPC endpoint (real value not shown)

})

if err != nil {

log.Fatalf("error making AWS session for Secrets Manager: %s", err)

}

sm := secretsmanager.New(smSess)

// Make rotator to handle invocation from Secrets Manager

r := rotate.NewRotator(rotate.Config{

SecretsManager: sm,

SecretSetter: MyRandomPassword{SecretsManager: sm},

PasswordSetter: ps,

})

// Run lambda using rotator (blocking call)

lambda.Start(r.Handler)

}

// --------------------------------------------------------------------------

type MyRandomPassword struct {

rotate.RandomPassword // handles Rotate() and Credentials()

SecretsManager *secretsmanager.SecretsManager

}

// MyRandomPassword.Handler() overrides rotate.RandomPassword.Handler()

// because the latter does nothing. This func handles manual invocation.

func (r MyRandomPassword) Handler(ctx context.Context, event map[string]string) (map[string]string, error) {

// Handle manually invoked lambda

return map[string]string{}, nil

}

The code above is not complete. It’s a demonstration and starting point. You should implement func (r MyRandomPassword) Handler to handle manual invocation requests like APR (see Default Provision Password). If you adapt the code above to work for your environment, build it as prl-bin, zip it into function.zip, and upload the zip file to the S3 bucket.

Terraform

Once the PRL code has been uploaded to S3, we can create the actual PRL in Terraform. Either TF or AWS checks/fetchs the function code from S3 on apply, so if that part is not correct, the TF apply will fail with some error.

Since running in a VPC is a requirement, we set our VPC IDs and the vpc_config block with our subnet IDs. These values aren’t shown because they will be unique to your AWS account. The TF code below supports the more complex PRL function code above (HTTP proxy for the RDS API and VPC endpoint for the Secrets Manager API).

# Security group: allow PRL only specific egress and deny all ingress.

resource "aws_security_group" "prl" {

name = "mysql-password-rotation-lambda"

vpc_id = "vpc-..."

egress {

description = "Secrets Manager via VPC endpoint"

from_port = 443

to_port = 443

protocol = "tcp"

cidr_blocks = ["10.0.0.0/8"]

}

egress {

description = "MySQL password rotation"

from_port = 3306

to_port = 3306

protocol = "tcp"

cidr_blocks = ["10.0.0.0/8"]

}

egress {

description = "RDS API via proxy"

from_port = 18080

to_port = 18080

protocol = "tcp"

cidr_blocks = ["10.0.0.0/8"]

}

}

# Lambda function: create the actual password rotation lambda (PRL) function.

resource "aws_lambda_function" "prl" {

depends_on = [

aws_security_group.prl,

]

s3_bucket = "prl-func"

s3_key = "function.zip"

function_name = "mysql-password-rotation" # Lambda func name

handler = "prl-bin" # Go binary name

role = aws_iam_role.prl-role.arn

runtime = "go1.x"

memory_size = 128

timeout = 60

environment {

variables = {

HTTP_PROXY = "http://proxy:18080"

HTTPS_PROXY = "http://proxy:18080"

NO_PROXY = ".vpce.amazonaws.com"

}

}

vpc_config {

subnet_ids = ["subnet-...", "subnet-..."]

security_group_ids = [aws_security_group.prl.id]

}

}

# Change default invoke configuration to lower timeout and retries because

# the PRL handles timeout and retries internally.

resource "aws_lambda_function_event_invoke_config" "prl" {

function_name = aws_lambda_function.prl.function_name

maximum_event_age_in_seconds = 300 # 5 min

maximum_retry_attempts = 1

}

# Resource-based policy: allow Secrets Manager to invoke the PRL.

resource "aws_lambda_permission" "prl-invoke-by-secretsmanager" {

statement_id = "AllowExecutionFromSecretsManager"

action = "lambda:InvokeFunction"

function_name = aws_lambda_function.prl.function_name

principal = "secretsmanager.amazonaws.com"

}

A few important points about the TF code above:

Security group: The egress rules are strict and required for the more complex example of the function code above. Port 443 allows TLS connections to the Secrets Manager API via VPC endpoint. Port 3306 allows connections to MySQL (RDS), which is pretty useful for a MySQL password rotation lambda. And port 18080 is the web proxy port because we connect to the public RDS API instead of using a VPC endpoint. The CIDR ranges will also be specific to your environment.

Lambda function: In the

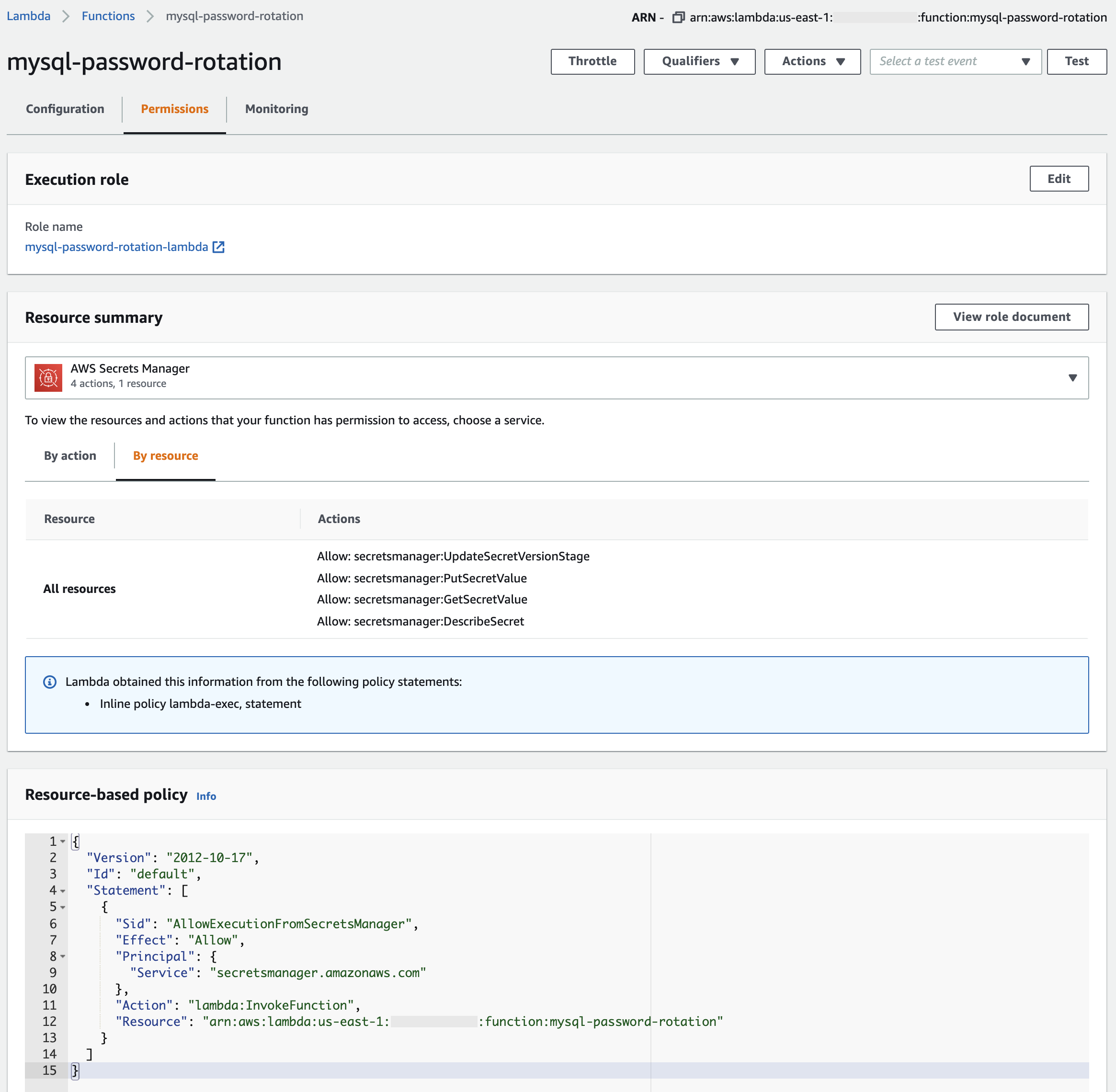

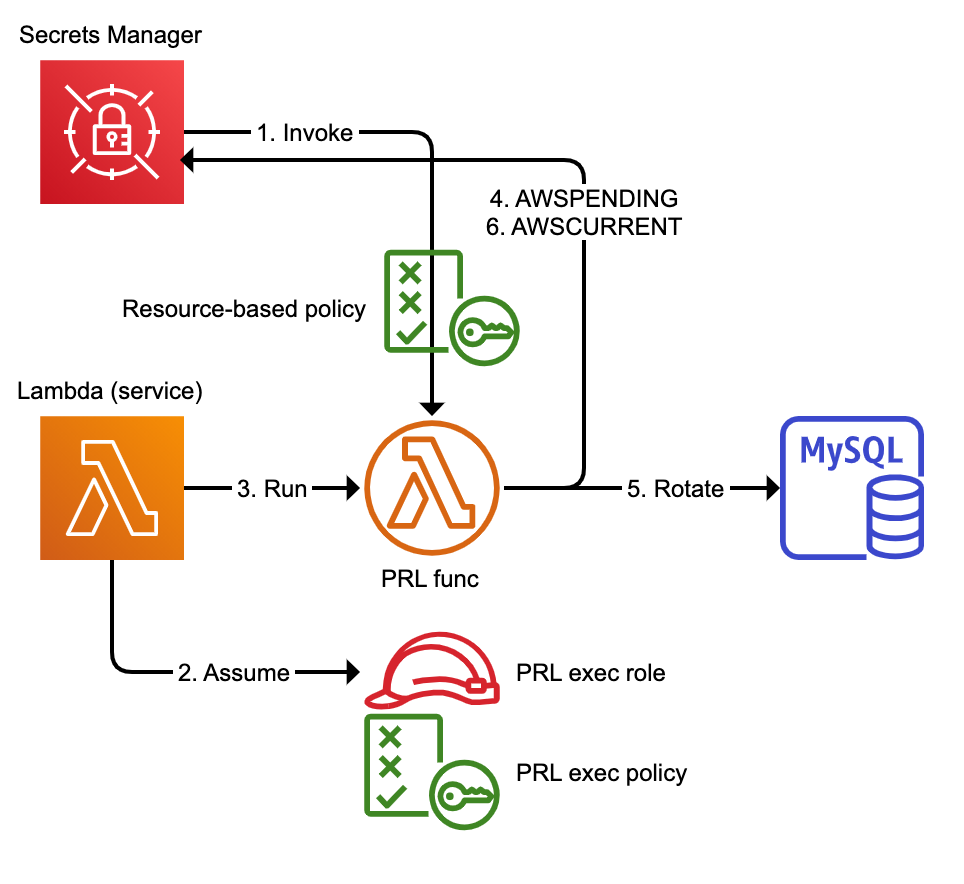

enviromentblock we inject the standardHTTP_PROXYandHTTPS_PROXYvalues which most normal software automatically uses. But we need to exclude VPC endpoints (i.e. do not go through the web proxy to reach a VPC endpoint), so we setNO_PROXY = ".vpce.amazonaws.com".Resource-based policy: The last Terraform resource defines a resource-based policy for the PRL. You can see it in the AWS console for the PRL by clicking Permissions (shown below). Whereas the execution role/policy defines what the PRL can do when it’s running, the resource-based policy defines what can invoke the PRL. If you click the “Info” link next to “Resource-based policy” in the AWS console it explains: “You use a resource-based policy to allow an AWS service to invoke your function.” Allowing the Secrets Manager service to invoke the PRL is the whole point. The diagram below helps clarify the execution role/policy vs. the resource-based policy during the PRL flow when invoked by Secrets Manager.

The diagram above shows the PRL flow when invoked by Secrets Manager:

- Secrets Manager invokes the PRL iff the resource-based policy allows.

- Lambda service assumes the PRL execution role, which has various policy privileges.

- Lambda service runs the PRL (lambda function code) as the PRL exec role.

- Since Secrets Manager invoked the PRL, first step is to create a new, pending secret (staging label = AWSPENDING).

- PRL rotates (sets) the MySQL user password to the pending secret value.

- PRL makes the pending secret the current secret (staging label = AWSCURRENT).

Note: the four steps of Secrets Manager rotation are not shown. In this diagram, step 4 is equal to rotation step 1; step 5 is equal to rotation steps 2 and 3 (set and verify), and step 6 is equal to rotation step 4.

Secrets Manager

The last piece of the puzzle is the secret in Secrets Manager:

# Create secret with MySQL app user password.

# This is just the secret resource, no value yet.

resource "aws_secretsmanager_secret" "mysql-password" {

depends_on = [

aws_lambda_permission.prl-invoke-by-secretsmanager,

]

name = "mysql-app-password"

description = "MySQL app user password"

recovery_window_in_days = 0

}

# Initialize secret with default provision password (DPP). This sets the

# secret value, which is JSON doc containing MySQL username and password.

resource "aws_secretsmanager_secret_version" "mysql-password" {

depends_on = [

aws_secretsmanager_secret.mysql-password,

]

secret_id = aws_secretsmanager_secret.mysql-password.id

secret_string = jsonencode({

username = "app"

password = "default_provision_password"

})

}

# Enable rotation with PRL. This causes the initial password rotation (IPR).

resource "aws_secretsmanager_secret_rotation" "mysql-password" {

secret_id = aws_secretsmanager_secret.mysql-password.id

rotation_lambda_arn = aws_lambda_function.prl.arn # ~~ PRL ~~

rotation_rules {

automatically_after_days = 1

}

}

# Wait 20s after initial password rotation (IPR) before creating db instances.

# The PRL is async, so IPR happens in the background. The resource that

# creates RDS instances should depend on this resource so that the instances

# start creating 20s after IPR was started.

resource "time_sleep" "wait-for-password-rotation" {

depends_on = [

aws_secretsmanager_secret_rotation.mysql-password,

]

create_duration = "20s"

}

The Secrets Manager resources are pretty straightforward. Be sure to set automatically_after_days to your rotation requirements.

Summary

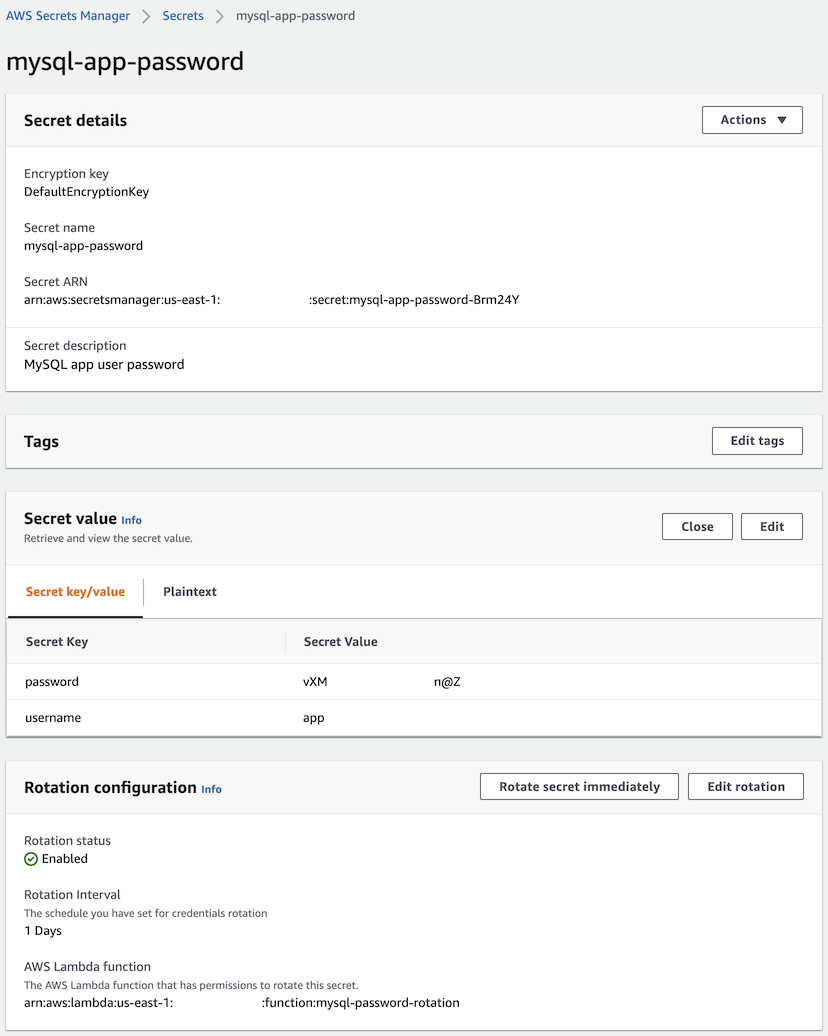

This page covers a lot of information. It’s not easy to grasp all at once; it takes times. But when it all comes together and works, you’ll see the four-step rotation executed by Secrets Manager logged in CloudWatch Logs, and the secret will look like:

The password is a random string (obscured in the image) and rotation is enabled.

At the start, one might think that MySQL password rotation using Amazon RDS for MySQL, AWS Secrets Manager, and AWS Lambda is a simple matter: just create a Lambda, use default code and settings, and voilà—it works! But if you have read this entire page, then you have learned the many reasons why that’s not true. I wish I had known at the start that:

- The default AWS PRL is not sufficient and does not work out of the box; don’t waste time with it

- There are no high-quality open-source PRL packages (so I wrote one: square/password-rotation-lambda)

- Manually invoking the PRL is as necessary as automatically invoked by Secrets Manager

- Lambda concurrency requires careful attention to detail and programming, especially wrt Secrets Manager rotation

- Secrets Manager is helpless when rotation (the PRL) fails

- Do not leave the AWSPENDING staging label, it blocks Secrets Manager rotation

- Secrets do not deleted by default, they’re scheduled for deletion which blocks recreating secrets

- Initial password rotation—everything already mentioned

- MySQL password rotation with AWS Secrets Manager and Lambda is a careful orchestration of many resources and user-specific code

Database password rotation is very important and should be implemented for every database, especially databases in the cloud. Hopefully this page makes it a lot easier for you to implement password rotation in your environment.

Copyright 2025 Daniel Nichter