Monitoring Multi-threaded Replication Lag With Performance Schema

Used to be that replication lag was as simple as Seconds_Behind_Master (renamed to Seconds_Behind_Source).

But with multi-threaded replication (MTR) this is no longer the case.

It’s time to relearn replication lag monitoring using Performance Schema tables.

This is a three-part series on replication lag with MTR and the Performance Schema:

| Part | Topic |

|---|---|

| 1 | Group commit and trx dependency tracking |

| 2 | Replica preserve commit order (RPCO) |

| 3 | Monitoring MTR lag with the Performance Schema |

Links to each part are in the upper right ↗ (or top on small screens). This part presumes you’ve read parts 1 and 2.

TL;DR

This isn’t the best solution, in my opinion, but it’s quick and reliable (the author of the gist if a MySQL expert: Frédéric Descamps1):

- Install lefred/mysql_8_replication_observability.sql

SELECT * FROM sys.replication_lag;

Tables

Although SHOW REPLICA STATUS (formerly SHOW SLAVE STATUS) still works, these Performance Schema tables are the new and more insightful way to monitor replication:

replication_connection_status

└── replication_applier_status_by_coordinator

└── replication_applier_status_by_worker

Before explaining those tables, let me point out:

- Table

replication_applier_statushas basically no useful information - There are other tables, but only the three above are required for replication lag (and status) monitoring

The three tables above are joined on channel name that has an aptly named column: CHANNEL_NAME.

However, I’ll gloss over MySQL replication channels; instead, let’s presume only the default channel that is rather poorly named: "".

Yeah, the default channel name is an empty string.

(I don’t know why; naming things is difficult.)

So when I write stuff like “table x contains …”, I mean per channel.

replication_connection_status- The

replication_connection_statustable contains I/O thread information. (For example, columnSERVICE_STATEmaps toReplica_IO_RunningfromSHOW REPLICA STATUS.) Since a replica I/O thread fetches binary log events from a source and puts them in the replica’s relay logs, this table provides information about that segment of replication: source → replica relay logs. A problem here is a problem in the source, network, I/O thread, or relay logs. replication_applier_status_by_coordinator- With MTR, a coordinator thread distributes transactions from the relay logs to worker (SQL) threads.

Since the coordinator only distributes transactions—it doesn’t apply them—this table isn’t as important as the previous or next table.

However, column

SERVICE_STATEin this table is equivalent toReplica_SQL_RunningfromSHOW REPLICA STATUS, which is important to monitor in case a problem stops all SQL threads. replication_applier_status_by_worker- The

replication_applier_status_by_workertable is the most important because it tracks each transaction (by GTID) applying and applied—with timestamps—by each worker thread (SQL thread). (It also tracks errors and retries.) Replication lag is calculated from either the applying or applied timestamps. Since this table (and the previous two) contain raw data, you have to calculate replication lag by querying the tables and handling various edge cases.

Querying

Currently, there’s no industry standard for querying the replication-related Performance Schema table described above. If you’re a DBA, you should learn the raw data each table provides in case you need it. If you’re a developer, you can probably rely on whatever tools and monitoring systems you use to do the right thing—however, “trust but verify”.

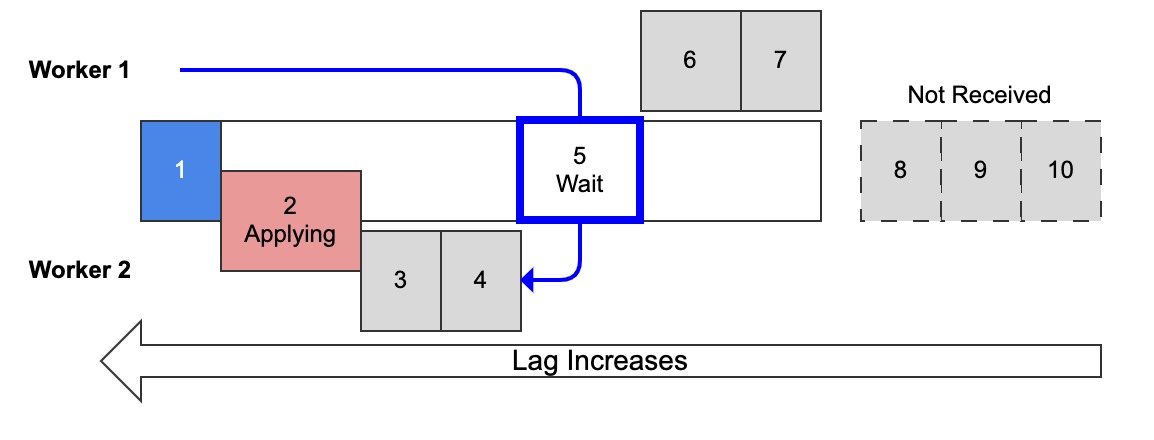

To understand the cryptic queries that follow, let’s recall diagram 4 from part 2 of this series, Replica Preserve Commit Order and Measuring Lag:

Diagram 4: Multi-threaded replication with replica preserve commit order ON, worker 1 waiting to commit

A key point from the part 2 of this series: With MTR, replication lag is measured from the oldest applying (or last applied) transaction.

Transaction 1 is applied. Transaction 2 is applying. Transaction 5 is applied but not committed.

Actually, transaction 5 is a problem for terminology: it’s applied (the worker is done making changes), but since it’s waiting on previous transactions to commit, it shows up in table replication_applier_status_by_worker as applying.

Observing this waiting state is discussed later in Waiting for Commit Order.

It doesn’t affect the query because replication lag is measured from the oldest applying transaction, which is transaction 2 in this example.

Simple

The simplest possible query for MTR lag is:

| |

Normally, explaining a short SELECT statement is overkill—like AI-generated slop.

And if you study it long enough, you’ll figure it out.

But I’m sure you came here to be taught, not to be told “figure it out yourself”.

So let’s go line by line.

Plus, understanding this simple query is necessary to understand more complex queries.

- Lines 2 and 9

- There are multiple channels and multiple worker (SQL) threads per channel, so group by channel.

(Granted, the default channel name is an empty string, so this column won’t show anything.)

Grouping needs aggregation, which happens on lines 4 and 5, then again by

COALESCE. - Lines 3, 6, and 7

COALESCEreturns the first non-NULL argument, which is needed because a transaction is either applying or applied, so one of the values will be NULL. Actually, there’s a third possibility that line 6 handles: a worker has not seen any transactions, so both values (applying and applied) are NULL. In this case, line 6 makesCOALESCEreturn zero, which is a choice about how to interpret and report lag for edge cases. True Zero Lag is another similar choice.- Line 4

- Line 4 returns the lag (in milliseconds) of the oldest applying transaction.

“Applying” is indicated by the column name:

APPLYING_TRANSACTION_IMMEDIATE_COMMIT_TIMESTAMP.MIN()is used because there are multiple workers and we want the oldest applying transaction. (These are timestamps, so minimum == oldest.) In diagram 4 above, transaction 2 is the oldest applying.

Why not measure from transaction 5? Because all the MySQL experts I’ve talked with agree: measure from the low watermark because this is safer and more conservative given possible gaps. In this example, the gap is transactions 2, 3, and 4. If these transactions take a really long time (or cause an error), the replica might not actually be applied and committed up to transaction 5.

Consequently, MTR lag is worst case. (By historical contrast, single threaded replication lag reported bySeconds_Behind_Slavewas best case, presuming it was accurate.) MTR lag might be better than reported, but the reported worst case shouldn’t be wildly inaccurate.NULLIF()is required becauseAPPLYING_TRANSACTION_IMMEDIATE_COMMIT_TIMESTAMPcan be zero. So withoutNULLIF(), this line is always zero or non-zero, which means it’s always used byCOALESCE, which is wrong because the worker might not be applying; it might be idle with an applied transaction. SoNULLIF()makes this line return a value only if the column value is non-zero; else, it returns NULL andCOALESCEchecks line 5 for an applied value.

The rest of the line,TIMESTAMPDIFF(MICROSECOND, ..., NOW(6))/1000, returns the difference between now and the transaction timestamp in milliseconds. This is my choice: I think replication lag is best expressed in milliseconds because that’s reasonable precision for network latency and easy for monitoring systems to convert to human-readable values. - Line 5

- Line 5 returns the lag (in milliseconds) of the last applied transaction.

This line/value is used (by

COALESCE) only if no workers are applying a transaction. In this case, presumereplica_preserve_commit_order = ONand measure from the last applied transaction. In diagram 4 above, imagine that transactions 2–5 are all applied and no other transactions are applying; then lag is measured from transaction 5.

Why presumereplica_preserve_commit_order = ON? Read part 2: Replica Preserve Commit Order and Measuring Lag.MAX()is used to get the last applied transaction because, again, we presumereplica_preserve_commit_order = ONso there are no gaps. If you’re running withreplica_preserve_commit_order = OFF, then changeMAXtoMINon this line.

But this line/value might be NULL, too. For example, on startup (or replica reset), no worker is applying or has applied any transaction, so all values are NULL. In this case, line 6 causesCOALESCEto return zero.

This query works and is reasonably accurate when there’s constant replication activity (due to writes on the source) over a fast and reliable network.

Realistic

In production, a realistic query is like the one below that Frédéric once shared with me:

SELECT COALESCE(MAX(`lag`), 0) AS Seconds_Behind_Source

FROM (

SELECT MAX(TIMESTAMPDIFF(MICROSECOND, APPLYING_TRANSACTION_IMMEDIATE_COMMIT_TIMESTAMP, NOW(6))/1000) AS `lag`

FROM performance_schema.replication_applier_status_by_worker

UNION

SELECT MIN(

CASE

WHEN

LAST_QUEUED_TRANSACTION = "ANONYMOUS" OR

LAST_APPLIED_TRANSACTION = "ANONYMOUS" OR

GTID_SUBTRACT(LAST_QUEUED_TRANSACTION, LAST_APPLIED_TRANSACTION) = ""

THEN 0

ELSE

TIMESTAMPDIFF(MICROSECOND, LAST_APPLIED_TRANSACTION_IMMEDIATE_COMMIT_TIMESTAMP, NOW(6))/1000

END

) AS `lag`

FROM performance_schema.replication_applier_status_by_worker w

JOIN performance_schema.replication_connection_status s ON s.channel_name = w.channel_name

) required;

One major difference between this query and the simple one in the previous section: this one handles true zero lag, which is what the GTID_SUBTRACT(LAST_QUEUED_TRANSACTION, LAST_APPLIED_TRANSACTION) = "" line is doing: if the last queued transaction and last applied transaction are the same, then the replica is caught up (not lagging) insofar as can be determined from the replica.

So this query reports zero on a truly idle replica, whereas the simple query reports an ever-increasing lag value (the difference between now and the last applied transaction).

Frédéric wrote a more complex query in lefred/mysql_8_replication_observability.sql that also takes into account the I/O and SQL thread states. Taking thread states into account is a best practice because any lag value is dubious if the I/O or SQL threads have stopped.

For thorough production monitoring, even more data is needed.

But at some point a query will become too complex, making it too slow for monitoring (monitoring queries must be very lightweight) or too complex for humans to grok.

Consequently, I took a different approach in Blip: metrics/repl.lag/pfs.go.

At top is the query.

At bottom, in function lagFor, is where the raw data from the query is processed—with a lot of code comments to explain what’s going on and why.

Rather than repeat those code comments here, read them top to bottom in that function.

All these examples dance around the point; so let me state the point directly:

There’s no industry standard way to query Performance Schema tables for multi-threaded replication lag.

While we have much greater insights into replication now, we also have much more to understand and implement to glean those insights. And a few challenges still remain…

Challenges

Waiting for Commit Order

In part 2 I showed that replica preserve commit order (RPCO) does not noticeably impact replica throughput in benchmarks, and I concluded that RPCO is unlikely to affect real-world replicas unless there’s a perfect storm of inefficiencies on the source. But there’s that old adage again: trust but verify.

It is possible to verify this, but it’s unfortunately not convenient because the data is in the wrong place and the wrong type.

Ideally, table replication_applier_status_by_worker would have a column and counter like COMMIT_ORDER_WAITS—how easy would that be!

But instead, the data is found in:

- Table

threads - Column

PROCESSLIST_STATE - Value

"Waiting for preceding transaction to commit"

This is undocumented but correct: it exists in the source code and you can observe it with replica_preserve_commit_order = ON.

So while a counter would make measuring commit order waits really easy, it’s still possible with SQL like (enhancing the simple query):

SELECT

-- other columns

COALESCE(t.PROCESSLIST_STATE, '') -- here...

FROM

replication_connection_status r

JOIN replication_applier_status_by_coordinator c USING (channel_name)

JOIN replication_applier_status_by_worker w USING (channel_name)

JOIN threads t ON t.THREAD_ID = w.THREAD_ID -- and here

Then check for the string value in the monitoring app (or use SQL functions to match it in the SELECT clause).

To my knowledge, no tool or monitoring app does this—the state of MTR lag monitoring is nascent as of this writing.

This works but it’s not ideal because it relies on direct observation of an ephemeral state/value. Let’s say commit order waits occur 100 times a second. If a monitor checks every 1 second, it’ll only observe the state 1 time at best—it’ll miss the 99 other times. The only frequency at which the monitor might be accurate is checking 100 times per second, or every 10 milliseconds. But that’s unrealistic for a production monitor. This is why a real counter is needed: to record every occurrence between observations. But, alas, MySQL doesn’t have a commit order wait counter.

MTR Utilization

MySQL doesn’t currently provide any metrics related to multi-threaded replication utilization.

As of MySQL v8.0.27, replica_parallel_workers = 4 is the default, but there’s no easy or direct way to determine if all four SQL threads are utilized.

And unless you get really fancy with SQL, it’s not feasible to calculate in a query.

But first, let’s be clear (especially for developers and new DBAs): replica_parallel_workers = N does not mean a replica will use N threads; it means only that N threads are created and available to the coordinator that distributes transactions to the threads.

Why won’t a replica utilize all worker threads? Because MTR utilization depends on transaction parallelization that is identified and set at the source. To learn (a lot) more, read part 1: Group Commit and Transaction Dependency Tracking: Towards Multi-threaded Replication.

Also, replication is fast, so it’s possible that < N threads (or even just 1 thread) can apply transactions so fast that the coordinator never utilizes the other threads.

This is observable in replication_applier_status_by_worker when threads (workers) are never observed applying or having applied transactions.

This is also how MTR utilization can be calculated: workers applying / total number of workers * 100.

Currently, the only monitor that I’m aware of that does this is Blip: repl.lag.worker_usage.

Even if a monitor calculates that every 5 seconds, several minutes of data will show if the replica utilizes all threads or not.

To be really sure, wait 24 hours to capture intra-day highs and lows in the application workload.

If the data never shows 100% utilization, consider reducing replica_parallel_workers if set higher than 4.

Setting it to 2 might be reasonable, but don’t set it to 1 because that disables MTR and affects the tables, which might break monitoring that expects the tables to be working for MTR.

Do not—I repeat: do not—“set and forget” replica_parallel_workers to a high value like 16 or 32.

Even if the replica doesn’t utilize all threads today, some day you’ll do a backfill or schema change or something that will cause additional load on replication.

When that additional load reaches the replica and MySQL attempts to utilize too many SQL threads, it could overload the server since 16- and 32-core servers (or instances) are still common—especially in the cloud.

Even the MySQL manual warns against this (emphasis mine):

Increasing the number of workers improves the potential for parallelism. Typically, this improves performance up to a certain point, beyond which increasing the number of workers reduces performance due to concurrency effects such as lock contention.

I’m not saying never to set replica_parallel_workers to a high value.

If your replica is on dedicated bare metal with 64 cores, then maybe replica_parallel_workers = 16 is safe and reasonable.

What I’m saying is: measure and monitor MTR utilization for your application workload and set replica_parallel_workers to a value that keeps all (or most) threads busy all (or most) of the time without overloading the server.

True Zero Lag

Let’s first clarify: can lag ever truly be zero? Yes and no:

- Yes when—even if only for a brief moment—the source and replica have applied all the same binary log events and no more writes occur on the source. In that moment, lag is truly zero.2

- No, because whenever there is a write on the source, network latency must be greater than zero (due to the speed of light).

True zero lag means no SQL thread is applying and no additional transactions have been received. So from the replica perspective, it has caught up to the source.

True zero lag doesn’t mean “no problems”, it only means the replica is truly caught up at the moment, insofar as can be determined at the replica.

But of course, there might be a problem before the replica that creates false-positive zero lag.

For example, if the network fails silently, then lag will become zero but in reality the replica is falling further and further behind the source.

Or, if the network is really slow, then another infamous problem occurs: Seconds_Behind_Replica flaps between zero and a non-zero value as the replica receives events erratically.

An industry standard solution for avoiding false-positive zero lag and flapping lag is to use external replication heartbeats: periodic timestamp updates to a row in a table on the source.3 (Internal MySQL replication heartbeats are addressed later.) Then lag is calculated on the replica as the difference between now and that row timestamp. With heartbeats, lag is always > 0 because writes are expected. So regardless of the network, lag is calculated from the last heartbeat, and the value will keep increasing until the network is repaired and newer heartbeats are received and applied.

At least one cloud provider uses something like a VPN tunnel to secure replication channels. Problem is: the tunnel is invisible to us (the customer) and it can break. When it breaks, everything we can see is okay—the replica reports true zero lag—but MySQL isn't replicating. If you see this confusing situation in the cloud, ask your cloud provider if they've got a "ghost in the network".

External replication heartbeats are industry standard for measuring and monitoring lag, but they conflate three problems:

- The heartbeat program is broken

- Nothing is replicating (true zero lag)

- The replica can’t keep up

The third problem is the main reason for heartbeats, and they work well for it if set up correctly. Without digressing too far, heartbeat programs require precision, and precision requires effort.4 The industry has solved this problem, but it’s better to avoid it altogether.

The second problem can be inferred from the third once a DBA looks closely and rules out the third. It’s difficult to determine, though, because although engineers often pick on the network, in my experience the network is almost never the culprit—it’s one of the last things I suspect.

The first problem should be exceptionally rare, but when it occurs it causes a pager storm (a flood of alerts). Consequently, at scale it’s better to have less infrastructure for this reason: less things to break (and maintain).

Historically, the only options were Seconds_Behind_Source or an external heartbeat program.

And the choice was easy: heartbeats, because they work better.

But today, I think the Performance Schema tables are the better choice because they avoid the first problem, and they can accurately report the second and third problems separately. Depending on how the data is queried and values are calculated, true zero lag and flapping can be controlled (or munged). For example, the simple query acts like a heartbeat program: lag continues to increase if no newer transactions are received. But Frédéric’s realistic query detects true zero lag and reports zero.

In production, high lag and true zero lag should be monitored and alerted on.

When it’s high lag, look into write activity on the source and maybe increase replica_parallel_workers on the replica.

When it’s true zero lag, check the source and network (are they online?); figure out why transactions aren’t reaching the replica.

These are different problems that we can (and should) monitor now that it’s easy to do with the Performance Schema.

Blip is the only MySQL monitor that I know that uses the Performance Schema for replication lag.

It reports true zero lag and MTR utilization.

See its repl.lag metric.

What About…

Original vs. Immediate

Another benefit (and detail to pay attention to) is “original” versus “immediate” replication metrics. This is useful for multi-level replication topologies like,

A -> B -> C

where A is the source of B, and B is the source of C.

On C:

- immediate =

B - original =

A

The Performance Schema tables have pairs of columns like:

LAST_APPLIED_TRANSACTION_ORIGINAL_COMMIT_TIMESTAMPLAST_APPLIED_TRANSACTION_IMMEDIATE_COMMIT_TIMESTAMP

Be sure to query the right columns. The best practice is to use “immediate” by default.

If you use “original”, be sure to document this because, in the A -> B -> C example, “original” on C encompasses two network segments and an intermediate MySQL node (B).

So if “original” metrics show lag, it’s unclear if the lag is between A -> B or B -> C.

MySQL Replication Heartbeats

Ironically and confusingly, internal MySQL replication heartbeats cannot be used to measure replication lag because they’re not sent at consistent intervals. Checking Replication Status in the MySQL manual notes:

The source sends a heartbeat signal to a replica if there are no updates to, and no unsent events in, the binary log for a longer period than the heartbeat interval.

Even if they were sent at consistent intervals, MySQL records only when heartbeats are received, not when they’re sent.

(Performance Schema table replication_connection_status has two columns: LAST_HEARTBEAT_TIMESTAMP and COUNT_RECEIVED_HEARTBEATS.)

That’s the opposite of external heartbeats: they record time sent (ts) so that on a replica lag = now - ts.

Internal MySQL replication heartbeats are useful only for detecting a network outage, but true zero lag detects that, too. (External heartbeats detect it indirectly by reporting increasing lag.)

Bottom line: internal MySQL replication heartbeats aren’t heartbeats in the normal sense, and you don’t need them if you’re monitoring replication lag, so you can ignore them.

Seconds_Behind_Source

Is Seconds_Behind_Source still valid, accurate, or useful with multi-threaded replication?

Yes, kind of.

The MySQL manual for SHOW REPLICA STATUS says this:

When using a multithreaded replica, you should keep in mind that this value is based on

Exec_Source_Log_Pos, and so may not reflect the position of the most recently committed transaction.

That’s currently all it says.

The confusing part is: Exec_Source_Log_Pos for which transaction?

With MTR, there can be N-many transactions applying in parallel, therefore N-many corresponding Exec_Source_Log_Pos.

But since there aren’t many SQL threads by default, it probably doesn’t matter which one.

This also entails that Seconds_Behind_Source is calculated from an applying transaction, not an applied transaction, which is historically consistent: Seconds_Behind_Source (or Seconds_Behind_Master) reports zero when the replica is not applying a transaction for any reason.

If MTR lag monitoring with Performance Schema is overwhelming (or not supported by the tools you use), you can still use Seconds_Behind_Source.

It won’t lead you wildly astray; just consider a rough estimate.

Series Recap

In no particular order, here are the points I think every MySQL DBA should know and do (when applicable) when it comes to MySQL multi-threaded replication:

- Binary log group commit (BGC) still exists, even in MySQL 9.0

- The transaction commit process has three stages: flush, sync, commit

- BGC happens during the sync stage

- BGC always occurs (when possible) but BGC is not required to parallelize transactions on a replica

- Multi-threaded replication (MTR) relies on transaction dependency tracking that occurs on the source

- Dependency tracking happens mostly in the flush and commit stages, but also in the prepare phase of the two-phase commit (2PC)

- During the commit process, transaction dependency tracking identifies which transaction do not conflict

- Transactions that do not conflict can be applied in parallel on a replica

- Transaction dependency is encoded in binary logs by two values: sequence number and last committed (commit parent)

- With

WRITESET, the only relationship between BGC and MTR (including transaction dependency tracking and parallelization) is the commit process: BGC and transaction dependency tracking happen during commit; otherwise, BGC and MTR are unrelated - Set

binlog_transaction_dependency_tracking = WRITESETbecause it’s not the default in MySQL 8.0 - Use only

WRITESETdependency tracking;COMMIT_ORDERis far less effective and removed as of MySQL 8.4 - Upgrade to at least MySQL v8.0.27 but beware…

- Related sysvars where removed in MySQL 8.4 and 9.0; double check your my.cnf to avoid startup errors

- Ensure

replica_preserve_commit_order = ON(RPCO); the default changed as of MySQL v8.0.27 - RPCO has no noticeable effect on MTR throughput

- A replica can apply but not commit a transaction, which is how RPCO works: threads wait for previous transactions (identified by sequence number) to commit in order

- Transaction sequence numbers are not the same as GTIDs; the former is used only for transaction dependency tracking and parallelization

replica_parallel_workershas the most effect on MTR throughput- Tune

replica_parallel_workersjudiciously through measurement and observation (more is not always faster; sometimes it’s slower) - Measuring replication lag with MTR is best done by querying related Performance Schema tables, primarily

replication_applier_status_by_worker - With MTR, replication lag is measured from the oldest applying (or last applied) transaction

- Currently, there is no industry standard or best practice for querying related tables, reporting MTR lag, or measuring MTR utilization (or effectiveness)

- Currently, Blip is the only tool that uses Performance Schema for MTR lag

Seconds_Behind_Source(fkaSeconds_Behind_Master) is still valid with MTR but only a rough estimate- MTR does not guarantee faster replica throughput; the application workload and transaction dependency tracking determine how many transactions can be applied in parallel on a replica

- MTR does not make slow transactions faster, but it might help reduce lag if the slow transaction doesn’t block other transactions due to RPCO

- Replication lag is data loss. Never ignore replication lag. Use MTR with

WRITESET; this is the best practice and only option as of MySQL 8.4 and newer.

True zero lag is imperative for “cut over” operations, like blue-green upgrades. A DBA makes the source read-only to stop all writes. Then they wait for true zero lag on the replica to which they’re cutting over. ↩︎

pt-heartbeat and Blip use heartbeats. But Blip also uses—and defaults to—the Performance Schema. ↩︎

If you really want to know, read Better Replication Heartbeats. ↩︎

Copyright 2025 Daniel Nichter