Lessons From 20 Years Hacking MySQL (Part 1)

Randomness

I vividly remember 2004 when I decided to specialize in MySQL because the year before I was homeless and living in my car. It’s been a long road and an amazing journey ever since.

From 2004 to 2005 I worked 10-hour shifts in a data center as an entry-level support person. That’s how I gained wide and constant exposure to MySQL: tens of thousands of servers and web sites running MySQL. And Facebook had just launched, which tells you what kind of year 2004 and beyond were for MySQL and tech in general.

When I started to reflect on the last 20 years with MySQL, the first thought that came to mind was “Wow, what a success MySQL has been! What’s the lesson behind its success?” But as I kept digging into this question for a lesson, it kept eluding me.

The superficial answer is:

MySQL has been successful for over 20 years because it provides tremendous value as a relational database that’s fast, free, open source, easy to use, very well documented, and continually improved. There’s a job to be done and MySQL does it well: store, query, and retrieve data.

That’s true, no doubt about it. But then I remembered the survivor bias and the hindsight bias, so I kept digging.1

What surprises me about the success of MySQL are historical events like:

MySQL, which was released in 1995, survived the dot-com crash in 2000–2001.

MySQL became the most popular open source database despite not being the most advanced open source database. Early versions of MySQL (circa v3.23 and v4.0) had less features than some alternatives at the time. Subqueries and prepared statements didn’t appear until v4.1 in 2004. Even the default storage engine (MyISAM) was non-transactional for many years until bugs and performance issues were ironed out of InnoDB.

MySQL was quickly adopted by large tech companies: Yahoo, Google, Facebook, Cisco, and many more. Moreover, some of these companies made significant contributions to MySQL—notably Facebook and Google. That’s surprising because products normally struggle to win such large and important adoption.

MySQL survived two acquisitions: first Sun Microsystems, then Oracle. On the first, Monty forked MySQL to create MariaDB, which could have been the end of MySQL. On the second, the MySQL community was understandably worried that Oracle would kill MySQL, but it didn’t.

MySQL inspired a large and devoted community of experts, many of whom still chat online and show up at the same conferences. That’s surprising because life is full of changes and people change, yet somehow MySQL has remained a constant for so many of us.

There are more examples, but these are enough to realize that MySQL could have failed for many different reasons. As a product, it was not always a rock-solid, high-performance, shining example of relational database perfection.2 But it was (and still is) the most popular open source database. Accordingly, the unfiltered history of MySQL reveals many successes and failures, many steps forward and setbacks, many moments of good luck and bad luck.

Curious about these dichotomies, I started to dig widely and think about other products, other companies, my whole career, and much of my life. I found the same pattern of good luck and bad luck, steps forward and setbacks, successes and failures. Then I remembered a book I read long ago: Fooled by Randomness by Nassim Nicholas Taleb.

James Clear’s summary of Fooled by Randomness starts with a perfect three-sentence synopsis:

Randomness, chance, and luck influence our lives and our work more than we realize. Because of hindsight bias and survivorship bias, in particular, we tend to forget the many who fail, remember the few who succeed, and then create reasons and patterns for their success even though it was largely random. Mild success can be explainable by skills and hard work, but wild success is usually attributable to variance and luck.

This is why a lesson about the success of MySQL kept eluding me: randomness is an integral part of success.

For every success story there are “yes, but…” elements of randomness.

MySQL was adopted, battle tested, and improved by some of the largest tech companies of the early 2000s. Yes, but the timing was incredibly lucky: if MySQL hadn’t been developed 10 years earlier, and if it hadn’t survived the dot-com crash, then it’s very doubtful that MySQL would have been ready for those companies. The skill and ingenuity of Monty Widenius, David Axmark, and others3 was necessary for the success of MySQL, but history shows that it wasn’t sufficient: randomness, in the form of near perfect market timing, was integral to the success of MySQL.

Reflecting on the last 20 years of hacking MySQL, I’ve learned these lessons first hand and often many times over. I hope they’ll help you have an amazing journey, too.

Scope of Discussion

Everything that follows is scoped to the tech industry unless otherwise noted.

Do not presume that these lessons apply to other industries or one's life.

For example, in business failure is rarely one event, but in life failure can definitely result from a single event.

Randomness is an integral part of success

At first, it’s disconcerting to learn that randomness is an integral part of success because—to put it a little too dramatically—bad luck can ruin your business or product, and there’s nothing you can do about it. Imagine working hard to create a new relational database and start a company, then a mere 5 years later the industry crashes!

😭

Sound familiar? That’s the story of MySQL from 1995 to the dot-com crash of 2000–2001.

But the same story also proves an important point: randomness is unbiased. (Logically so: if randomness were biased, it wouldn’t be random.) Random good things can happen, too, and these permeate the history of MySQL.

🤩

My own story is similar. I’ve had my share of bad luck: failed businesses, broke, homeless, and so forth. But overall I’ve been successful thanks to a slim majority of random good luck:

| % | Part of My Success |

|---|---|

| 51 | Random good luck |

| 47 | Hard work and patience |

| 2 | Skill |

This is true for my 20 years with MySQL, my whole career, and my whole life. All the biggest successes of my life started with random good luck: right place, right time, right people—that kind of thing.

Good luck opens doors, but you have to walk through and climb the mountain on the other side. That’s where the 47% hard work and patience comes in: all the success stories I know took at least 5 years, but 10 years is more typical. It takes time to build value, and even longer to change the way people work.

And 2% skill? At this point in my career, I hope it’s not a conceit to say that I’ve got more skill than that. But along the way—climbing the mountain—success is built by operating a little beyond the current limits. Or, as David Bowie said:

If you feel safe in the area you’re working in, you’re not working in the right area. Always go a little further into the water than you feel you’re capable of being in. Go a little bit out of your depth. And when you don’t feel that your feet are quite touching the bottom, you’re just about in the right place to do something exciting.

For a product like MySQL, this meant operating in the established field of transactional RDBMS when its default storage engine was non-transactional. Its feet weren’t quite touching the bottom, but it grew up.

“Good luck” is a convenient term but not a useful concept because:

- It’s usually a one-time event, like winning the lottery. So what happens next? Years after?

- It doesn’t build or do anything. The MySQL source code didn’t coalesce randomly from nothing into a working database—that would be crazy good luck.

- We cannot create good luck. If we could, then it’d hardly be called “luck”.

Opportunity is a more useful concept because we can take advantage of and grow an opportunity. Importantly, we can bias towards success to tilt the odds of randomness in our favor.

You bias towards success through education, preparedness, hard work, and perseverance.

Biasing towards success works because opportunities are endless and all around us—often hidden or just out of sight, but all around us nevertheless. But if you don’t tilt the field in your favor, then you have even odds of success and failure because randomness is, tautologically, random.

If biasing towards success sounds like a “pick yourself up by the bootstrap” cliché, then think of it like a video game: you know success is possible (it’s programmed into the game), but you have to complete quests, get items, defeat bosses, and gain skills and experience. After awhile, success comes easily because you’re a high-level player.

Real life is surprisingly like a video game. Success is possible; it’s even programmed into the “game” because most people and most of the world wants you to succeed. But there are definitely enemies and bosses—competition and people who don’t want you to succeed—which is why success takes work.

Rigged Game

I'm keenly aware that the game of life is being rigged.

At first the problem seems to be certain people tilting the field in their favor, which limits or takes away opportunities from others.

But this is not the problem; opportunities are endless.

Galloway states the problem (5:07): "we artificially constrain supply to create aspiration and scarcity".

Near the end of the video he lists solutions.

This amplifies the need to bias towards success—especially education because you can't beat a game you don't understand.

MySQL was highly biased to succeed. Many smart people contributed to MySQL—education and hard work. Thanks to being open source, MySQL attracted and retained a community of smart people who learned and taught others—a virtuous cycle of education. And ten years of preparation plus perseverance through the dot-com crash put MySQL in the right place at the right time.

There’s one disposition related to preparedness and perseverance that I want to emphasize because it has served me very well, and I’ve observed it in other successful engineers, and I’ve seen it come into play many times for MySQL specifically and work generally: focus on the technical work; refuse to participate in the rest.

Even the best companies and communities will have politics, drama, bad managers, and all other types of disruptive issues that cloud or distort the technical work that everyone is supposed to be doing. And since “misery loves company”, people will try to distract you with, or draw you into, the mess. Never let them. Always politely steer the conversation back to technical work. If you can’t, then say nothing, take no sides, offer no opinions on other people, and exit (the meeting, situation, or—if necessary—company) as quickly and politely as possible.

I’ll share a story with you that exemplifies what I mean. To protect the innocent, I’ll retell it vaguely. One time (and thankfully only one time) I had a terrible manager. He gave me an ultimatum: finish a project by such-and-such date, or hand in my resignation. How would you respond?

Of course, I was pissed but I kept my mouth shut and only replied, “Let me think about it and let you know.” I took a day or two to cool off and consult with people I trust. Then I told that terrible manager, “No deal. I don’t play those kinds of games. I always do my best. If that’s not good enough, help me improve or fire me. And don’t feel bad about firing me: I’ve fired people before, too, so I know it needs to be done from time to time.” He dropped the ultimatum, but I discovered what kind of person he was: manipulative and self-serving. And I knew it was only a matter of time before he got himself fired because I knew his boss was smart and honorable and would soon make the same discovery. Sure enough, just a few months later he was fired on the spot.

This disposition is a magical shield. It will protect you from every attack at work. It will attract all the best people and opportunities to you. Hold on to it.

Success and failure are not random. Randomness is only part of success. Our effort, or lack therefore, is meaningful. MySQL hasn’t been successful for almost 30 years by good luck alone. Its success reflects some good luck and a tremendous amount of effort.

Past success guarantees nothing

The biggest failure of my career (so far) was Percona Cloud Tools.

Before VividCortex (acquired by SolarWinds4), and long before Datadog Deep Database Monitoring, Percona Cloud Tools (PCT) was the first fully-hosted MySQL query metrics SaaS product. I led its creation with a small team of developers at Percona. I knew from the start that it was a monumental task that would require long hours, so I kept track of my time: I averaged 72 hours/week for 2.5 years. Then PCT failed.

Here’s the fake champagne I poured for myself on July 1, 2015 when PCT officially shut down. Cheers!

Now with the benefit of 9 years of hindsight, I can confirm that PCT should have been a smash hit—a real cash cow—because similar products today are very popular and very expensive.

And by all accounts, nobody was better able and prepared to be successful with a product like PCT than me and Percona. Not only were we first to market, but I already had 10 years of success building and shipping MySQL tools.

So what went wrong?

(1) I was the wrong project lead which led to (2) poor initial quality which led to (3) taking too long to deliver a quality product which led to (4) running out of money which led to (5) a competitor taking the lead with a better product.

The specifics of those five don’t matter. What’s important is that none of them were random or bad luck. (One lead developer quit, but that was my fault for not guarding against that risk.)

The history of business is full of successful companies ceasing to be successful and ceasing to be. Like Sun Microsystems: it was successful enough to acquire MySQL for 1 billion dollars. Maybe MySQL would have done well at Sun, but we’ll never know because a mere two years later Oracle acquired Sun for 7.4 billion dollars.

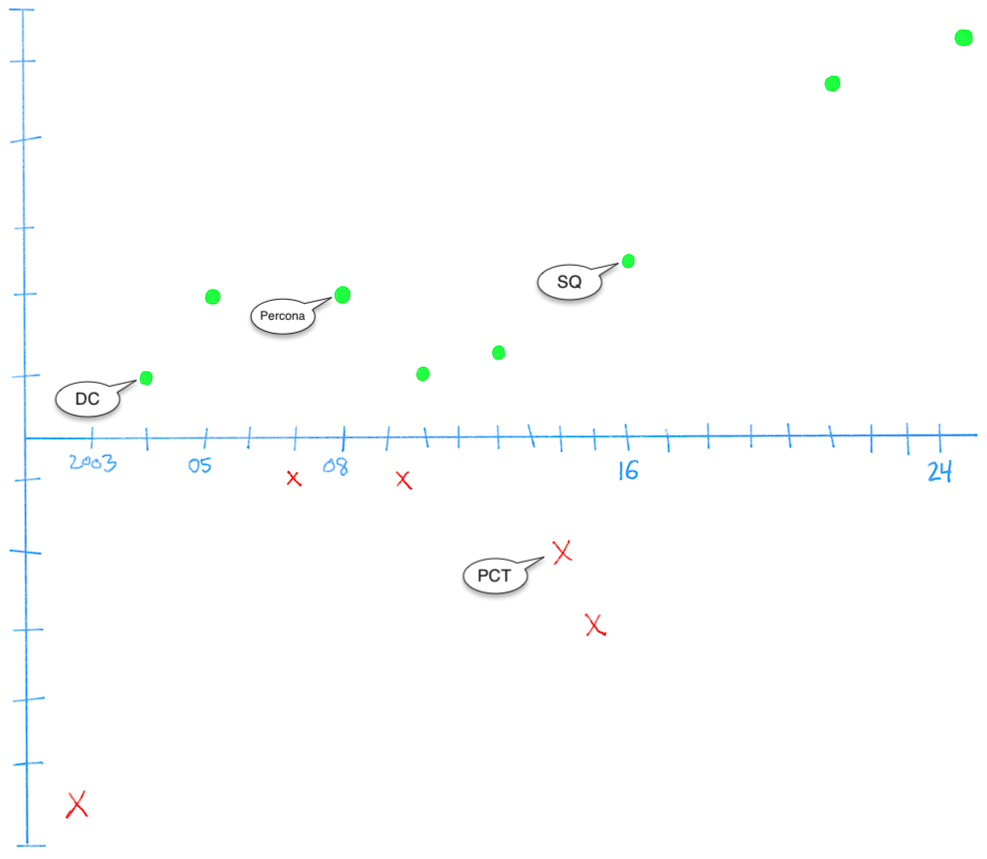

The last 20 years of my career exhibit the ups and downs that demonstrate how past success guarantees nothing:

Things have been going pretty well since I joined Block (fka Square) in 2016, but the past wasn’t all celebrations. PCT is the first red “X” under 2014/2015. The second, more negative, red “X” under 2015… personal stuff.

Most stories I know—personal, business, historical—have a similar graph of ups and downs, positives and negatives, good luck and bad luck. It begs the question: what’s the point of success—why keep trying—if the next thing you do might flop? Because the next thing (after the flop) can lead to the greatest success of your life. For me, that was 2003 → 2004 and 2015 → 2016.

None of this means you can’t have a series of successes. MySQL has been a series of successes: v3.23, v4.0, v4.1, v5.0, v5.1, v.5.5, v5.6, and v5.7. But v8.0? A flop in terms of respecting semver and patch-level backwards compatibility. Thankfully, that ended with v8.0.34 LTS.

None of this means that past success and experience aren’t valuable and formative. They are; they’re invaluable.

What this means is: be humble and realistic about past success and what, if anything, comes next.

I’ll share another story with you that exemplifies what I mean. I once started a new project with a very successful engineer who was leading the work. He had a new and very ambitious idea for the project. But I thought it was asinine, and I argued with him in private. He was convinced it would work and he was the lead, so “disagree and commit”.

The project failed miserably. The code worked as (crazily) designed, but there was no market for it. Imagine something like a six-wheeled car: technically possible, but why? Why!? :facepalm: That’s when I realized:

Neither age nor experience guarantees good ideas.

Engineers usually get better with time… but not always. Success has been know to make people go a little crazy or develop an overconfidence bias. Don’t let it happen to you.

What confuses me, though, is that the tech industry sometimes mythologizes the opposite: a young inexperienced outsider who, out of nowhere, disrupts an industry (or the world!), creates a unicorn business, and becomes an (eccentric) billionaire.

Even after 20+ years in tech, I’m honestly not sure what the industry values: fresh new ideas, or decades of experience? Probably both… because both are good. I think tech hasn’t quite figured out yet how to merge the two. Now that I’m on the right side of that “or”, this is a poignant issue for me. Change starts with awareness.

Failure is rarely one event

In business, failure is rarely one event but, rather, a series of failures. This is good and bad news.

The good news: we (the world) still have MySQL because its failures weren’t a series. Like any large and complicated programs, MySQL has always had bugs (some pretty serious) and rough edges. But in my experience, they never formed a series of failures that became so irksome that too many users thought, “Enough of this! Let’s use a different database.”

This is good news for other companies and products because it removes the burden and expectation of perfection. (Perfection is an unrealistic expectation in any case.) Users are patient and forgiving as long as a company maintains a track record of delivering value, fixing problems quickly, and working to benefit the customers not the bottom line.5

Especially during my early years hacking MySQL, its flaws were openly discussed and quickly fixed. MySQL, big tech companies, Percona, and the open source community all helped drive its rapid progress, which made its failures rapidly forgotten. I’ve never seen anything like it since, but I hope I do again.

The bad news: failure is a slow-moving problem that’s difficult to detect before it’s too late because it never seems imminent.

This has not happened to MySQL yet, but the history of tech is full of such stories: Gateway Computers, AOL, Yahoo, MySpace, Napster, Netscape, Borland, BlackBerry… Even Apple failed to Wintel until Steve Jobs came back and turned it around.6 And at the moment, Boeing has fallen from grace (emphasis on a grim pun).

In all cases, it took time to fail. Or worse: not fail entirely but become a shell of its former glory, a zombie business that makes people say “How is that company still in business!?”

When a business is failing, the technology cannot save it.

The business will insist otherwise, “If only we develop or acquire the next killer product, it’ll all be okay!” It has to insist otherwise because anything less than optimism will create a downward spiral of demoralization that will undoubtedly hasten the end. This is why CEOs never say something like, “Yes, it’s all gone to shit. But we’ll fix it.”

What can you do? What should you do? Nothing. Hold onto your magical shield: focus on the technical work; refuse to participate in the rest.

Only the founders or executives can fix a failing business. The reason is simple: only they are empowered to make potentially big or sweeping organizational changes. Engineers can’t. Line managers can’t. Middle managers can’t.

For brevity, I’ll omit a large amount of nuance on this topic and, instead, deliver the point and advice for engineers: don’t burn out trying to fix a business that you’re not empowered to fix.

I’ve seen more than a few good engineers burn out this way. Learning how to raise issues and call out problems without being be labeled a naysayer or obstructionist is a difficult skill to master.7 As an engineer who builds and fixes things, the temptation to fix the business is powerful, but until you have that skill, tread very lightly and hold onto your magical shield.

Remember Drizzle? TokuDB? Schooner? Falcon? MySQL has survived for more than 20 years, but the graveyard of failed businesses and products is crowded. ↩︎

The source code is very messy and cryptic. Some confirmed bugs aren’t fixed for many years. Blocking DDL is still common.

SHOW STATUShas become polluted with non-status variables. 8.0.x changes before .34 were chaos—glad Kenny fixed this. ↩︎People like Peter Zaitsev, Vadim Tkachenko, Mark Callaghan, Domas Mituzas, Yasufumi Kinoshita, Brian Aker, Laurynas Biveinis, and Jeremy Cole—just to name a few. ↩︎

https://www.solarwinds.com/database-performance-monitor/vividcortex ↩︎

I’ve spent 16 of the last 20 years at two companies: Percona and Block (fka Square)—8 years each. Among many reasons, a critical one for me is that both companies truly work for their customers’ benefit. ↩︎

Then Microsoft failed to Apple on music players and smartphones. I don’t think I’ve ever seen a Zune player. ↩︎

Rule #1 for raising issues or calling out problems without being be labeled a naysayer or obstructionist: offer realistic solutions or ways to improve. ↩︎

Copyright 2025 Daniel Nichter