Group Commit and Transaction Dependency Tracking

Towards Multi-threaded Replication

MySQL 8.0 and newer change and improve how we measure and monitor replication lag. Even though multi-threaded replication (MTR) has been on by default for the last three years (since v8.0.27 released October 2021), the industry has been steeped in single-threaded replication for nearly 30 years. As a result, replication lag with MTR is a complicated topic because it depends on version, configuration, and more. This three-part series provides a detailed understanding, starting from what was originally an unrelated feature: binary log group commit.

This is a three-part series on replication lag with MTR and the Performance Schema:

| Part | Topic |

|---|---|

| 1 | Group commit and trx dependency tracking |

| 2 | Replica preserve commit order (RPCO) |

| 3 | Monitoring MTR lag with the Performance Schema |

Links to each part are in the upper right ↗ (or top on small screens).

These topics are closely related—they depend on each other. If you’re new to these topics, start here (part 1). If you’re familiar with them, jump to part 3 (once it’s published).

Group Commit

Before looking at MySQL binary log group commit (BGC), consider the simplest way to code durability on transaction commit: use a mutex to serialize writes and flushes to disk. In pseudo-code, the thread for every client would do something like:

/* pseudo code */

LOCK(log_mutex);

write_data();

fsync();

unlock(log_mutex);

Even a junior programmer can see that that code is going to be really slow on a busy database: heavy mutex contention plus slow, individual writes and syncs. The only hope for performance is blazing fast storage (that’s probably really expensive).

Since every commit must be made durable, that code quickly hits the physical performance limits of the storage, particularly IOPS and write latency. Surprisingly, the real MySQL code prior to group commit was similar—writing and syncing each transaction, one by one.

Before 2012 and group commit, how did MySQL achieve high transaction throughput with durability? A single spinning disk can do about 200 IOPS at best. Big tech companies would use enterprise-grade SSD and RAID to achieve thousands of IOPS per server. When that wasn't enough, the solution was (and still is) sharding: using hundreds or thousands of servers. For example, being conservative, a big tech company circa 2012 could achieve 1 million IOPS total by having 200 MySQL shards each doing 5,000 IOPS.

The solution to improve transaction throughput with durability is to group writes and syncs. Hence group commit added in MySQL 5.6 (circa 2012):

Indeed, the entire point of performing a group commit of the binary log is to not flush the binary log with each transaction and instead improve performance by reducing the number of flushes per transaction.

Grouping doesn’t solve all performance problems because some things can’t be grouped, or grouping causing more work. But it works in this case because grouping is somewhat cost-free due to the fact that transactions must already be serialized for logging in both the InnoDB redo logs and the MySQL binary logs.

Imagine that the transactions are A, B, C, and D—committed in that order.

A system can write and flush (sync) them in groups (denoted by [ ]) that preserve the original commit order:

[A] ... [B] ... [C,D][A,B] ... [C,D][A,B,C] ... [D][A,B,C,D]

The last example is the best performance-wise: 1 write/flush for all 4 transactions.

Commit order can be flexible. There are cases (and MySQL configurations) in which the order of the example above can be different yet valid. For simplicity, let's presume that the original commit order is preserved.

The idea of group commit is simple but the implementation is not because the difficult question is: how should MySQL get transactions to group together? If it waits some amount of time to collect transactions, then how long should it wait? If it waits to collect N number of transactions, then how large should N be? Worst case, every group is less than N, so every transaction commit is delayed by the wait time—wasted time is created in an attempt to reduce wasted work. Regardless, this is precisely what MySQL does because nobody has figured out a better method:

These sysvars are 0 (off) by default, but MySQL always groups commits when possible, even when these sysvars are zero. I’ll explain why later. For now, the point is that these sysvar do not enable group commit, they only tune group commit.

How should these two sysvars be tuned? There’s no definitive answer, no best practice, no industry standard.1

MySQL expert Jean-François (J-F) Gagné has probably tested, written, and presented more on this than anyone else, like A Metric for Tuning Parallel Replication in MySQL 5.7 and various conference presentations you can find online. The TL;DR is: the longer MySQL waits, the more transactions it can group together. However, to be clear…

As of MySQL v5.7.6, transaction dependency tracking and MTR do not depend on binary log group commit.

I highlight the previous because there can be confusion and wrong information for two reasons. First, logical clock v1 coupled trx dependency tracking, BGC, and MTR for a few versions (v5.7.2–v5.7.5 inclusive), but this stopped being true more than 9 years ago. Second, as diagram 1 shows (below), trx dependency tracking happens during BGC, which is still true as of MySQL 9.0, but group commit does not determine transaction dependency. Transaction dependency is first identified by locking intervals on commit, then enhanced by writesets.2

That said, to deeply understand group commit and how it ties into multi-threaded replication, it’s necessary to first understand the transaction (trx) commit process because it’s all woven together.

Trx Commit Process

There’s a complex diagram below, but we need to lay some groundwork first, starting with two points that are clear and understandable:

- MySQL uses a two-phase commit (2PC). (Another good, longer explanation of 2PC: Distributed Transactions & Two-phase Commit by Animesh Gaitonde.) So there are prepare and commit code paths called in that order: prepare → commit.

- The complete trx commit process occurs on explicit

COMMIT,autocommit, or implicit commit (due to a DDL statement, for example).

Here are two more points that usually are not clear or immediately understandable:

- Binary log code (

class MYSQL_BIN_LOG : public TC_LOGinsql/binlog.cc) acts as the 2PC transaction coordinator and it implements the storage engine “handlerton” interface.3 - Every statement “commits”: 2PC code is called after every statement, not just

COMMIT.

Even after 20 years hacking MySQL, I don’t know why the binlog acts as the transaction coordinator. Regardless of why, this means the diagram below is mostly binlog code playing two roles; only the green parts (InnoDB) are not binlog code.

Every statement “commits” means that the 2PC code is called after every statement, but the code does different things depending on the statement.

Even a SELECT “commits”, but most of the 2PC code returns early because it’s not a transaction commit.

To disambiguate this conflation of the term “commit”,4 let’s use:

| Term | Refers To |

|---|---|

| (trx) commit | End of trx on explicit COMMIT, autocommit, or implicit commit |

| statement commit | End of query, not a trx commit |

Statement commits are important because they start (or restart) the locking interval described later. But for now, let’s focus on the trx commit process that’s executed by one or more threads concurrently:

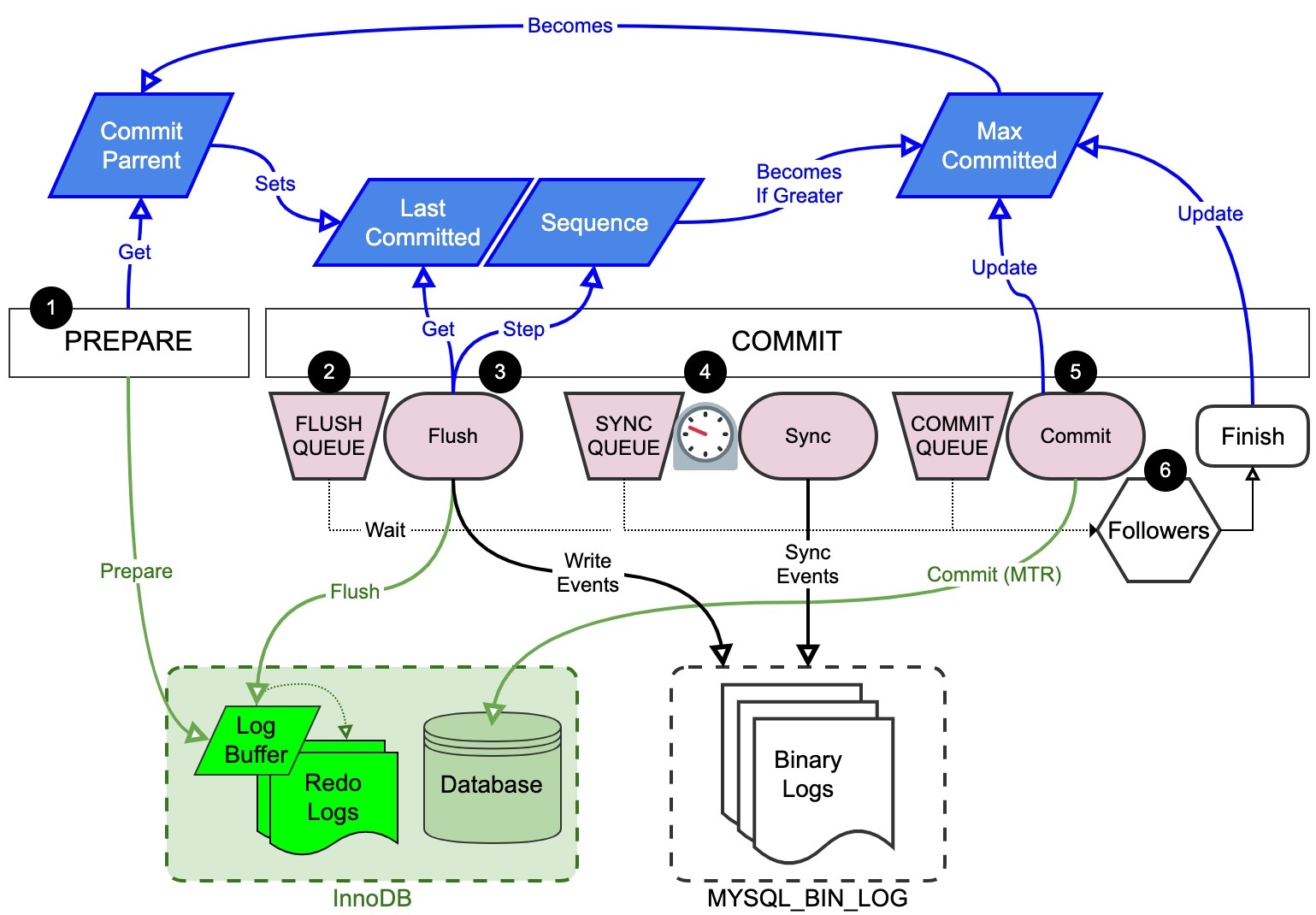

Diagram 1: MySQL transaction commit process with binary log group commit

Blue items at top are logical clock values explained later. The prepare and commit phases are show in the middle. Black circle numbers are callouts used to describe the process below, step by step. Light magenta (pinkish) items are binary log group commit queues and processes. Green items at bottom left are InnoDB components. And MySQL binary logs are shown at bottom right.

The following glosses over the BGC stages—Flush, Sync, Commit—that are detailed in the next section.

- Prepare Phase

- Get commit parent to record later as

last_committedin binary logs - Write InnoDB prepare records to in-memory log buffer

- A

COMMITstatement does nothing in the prepare phase

- Flush Stage: Queue

- Enter flush queue and check if it was empty (was thread first in queue?):

- False: thread becomes a follower, go to step 6 and wait using

pthread_cond_wait - True: thread becomes the leader and continues…

- False: thread becomes a follower, go to step 6 and wait using

- Flush Stage: Process

- Take all threads in flush queue

- The time between step 2 and now is virtually zero—a few lines of code

- Flush InnoDB prepare records

- Step and assign logical clock values to each trx to record later as

sequence_numberin binary logs - Write (but don’t flush) transactions to binary logs

- Each trx is recorded with

<last_committed, sequence_number>

- Each trx is recorded with

- Sync Stage

- Enter sync queue and check if it was empty (was thread first in queue?):

- False: thread becomes a follower (even if it was leader for flush stage), go to step 6 and wait using

pthread_cond_wait - True: thread becomes the leader and continues…

- False: thread becomes a follower (even if it was leader for flush stage), go to step 6 and wait using

- Wait

binlog_group_commit_sync_no_delay_countorbinlog_group_commit_sync_delay- This wait is how those sysvars can increase group commit size: the longer the wait, the more threads will enter the sync queue before…

- Take all threads in sync queue and flush binary logs (sync process)

- This is a binary log group commit: the group is all trx for all threads taken from the sync queue

- Commit Stage

- Enter commit queue and check if it was empty (was thread first in queue?):

- False: thread becomes a follower (even if it was leader for flush stage), go to step 6 and wait using

pthread_cond_wait - True: thread becomes the leader and continues…

- False: thread becomes a follower (even if it was leader for flush stage), go to step 6 and wait using

- Update global max committed (if leader sequence number is greater)

- Write and sync InnoDB commit records to finalize changes in the database and release locks

- Wake Up Followers

- Commit stage leader calls

pthread_cond_broadcast - Follower threads wake up and update global max committed (if follower sequence number is greater)

The trx commit process is concurrent at some points and serialized at others. Diagram 1 looks serialized, but generally speaking steps 1–3 are concurrent, step 4 is (mostly) serialized, and steps 5–6 are (mostly) concurrent. And other details, like how InnoDB has its own type of group commit,5 are not shown.

It might help to visualize the trx commit process as a pipe:

Diagram 2: Transactions enter randomly but exit with an order

Transactions enter randomly and concurrently but exit with an order: sequence_number (the second value in the < > pair).

The ordering happens in step 3, the flush stage process, because that’s when each transaction is given the next sequence number (from the logical clock) and written to the binary logs.

A log on the source is required to record changes, but on a replica it creates a problem for MTR: without encoding some kind of trx dependency tracking, the concurrency entering the pipe is lost. This is what logical clock and writeset provide: trx dependency tracking. But first, the BGC stages: flush, sync, commit.

"Commit parent" and

last_committed are synonymous."Trx N" means transaction with

sequence_number = N.Flush, Sync, Commit

Binary log group commit is implemented as three stages during the commit phase: flush → sync → commit. For each stage, there’s a queue and a process (function): flush queue and flush process; sync queue and sync process; commit queue and commit process. In digram 1 above, this detail is called out by steps 2 and 3, and it’s important because the tiny interval between queue and process is where, when, and how concurrent threads might pile up in a queue (primarily the sync queue), causing a group commit.

- Flush

The flush stage has no wait between queue and process. It’s one function call (enter queue) followed almost immediately by the other (process queue). Since there’s virtually no interval (a matter of clock cycles), threads are unlikely to pile up in the flush queue.6 Regardless, I can confirm that the flush queue works as intended because I can pause threads with a debugger to force a pile up in the flush queue. But on a real server, I would expect threads to pass through the flush stage one by one unless the server has extreme concurrency, is heavily loaded, or both.

During the flush stage, InnoDB flushes prepare records (from the prepare phase) to its redo logs. For a truly durable two-phase commit, this is necessary because prepare records cannot be lost, so they must be synced to disk. But given the previous (threads are unlikely to queue up during the flush stage), is this efficient? I’m not an expert on InnoDB internals, so I could be wrong here, but I’m pretty sure the answer is yes. The log buffer is holding prepare records in memory, so there should be one sequential write (buffer to redo log files) and flush by the flush stage leader. (Each BGC stage is executed by a single leader thread.) Since we’re examining binary log group commit (part of MySQL, not InnoDB), I’ll leave this as an open question.

Also during the flush stage, MySQL writes (but does not flush) events to the binary logs. This is fast because it’s a single thread (the stage leader) doing sequential writes, which the operating system or storage device is most likely going to cache.

Just before writing a transaction to the binary logs, MySQL steps the logical clock to set thesequence_numberof the transaction, then it fetches thelast_committed(commit parent) value that was set in the prepare phase. Both values are written into the binary logs.

Sync

The sync stage has a wait between queue and process, shown at step 4 (the clock) in digram 1. The wait is created bybinlog_group_commit_sync_no_delay_countandbinlog_group_commit_sync_delay. This is the crux of binary log group commit: by putting a wait after the sync queue, threads will pile up in the sync queue. When the wait expires, the leader takes all threads in the sync queue and flushes the binary logs. (If a thread is in the sync queue, its trx must have been written to the binary logs in the flush stage.) These threads and transactions are one group commit.

When BGC was introduced in 2012, spinning disks were still common, so a sync was quite slow: on the order of milliseconds. Today, a sync can take only microseconds on flash storage, but it’s still the slowest part of making committed transactions durable.

At this point in the trx commit process, the changes are truly durable. Even if MySQL crashes after the sync, MySQL and InnoDB can (and do) recover from the binary logs and InnoDB prepare records. But the 2PC isn’t done yet, so all the threads in the group commit advance to the final stage: commit.Commit

During the commit stage, the leader thread updates the global max committed value that (other) threads entering the prepare phase read as their commit parent. Since the leader might not have the highest sequence number, follower threads also update the max committed once they’re woken up at the end of the commit process.7

Last but not least, InnoDB commits transactions, which is to say that it finalizes transactions in the database and releases all locks. If you think the preceding is complex, it’s nothing compared to what InnoDB does to make committing many concurrent transactions fast and efficient: MySQL 8.0: New Lock free, scalable WAL design. Long story short, InnoDB does a type of group commit, too.

Let’s step through a simplified example with five transactions, a–e, flowing through the three group commit stages to see how they may or may not group and how they pick up a commit parent value (denoted by < >).

Time, t, runs top to bottom:

t| FLUSH | SYNC | COMMIT

-|----------------|---------------|--------------

1| < >a1, b1, c1 | |

2| < >d1 | < >a1, b1, c1 |

3| | < >d1 | < >a1, b1, c1

4| <c1>e1,c2 | | < >d1

5| | <c1>e1,c2 |

6| | | <c1>e1,c2

At time t:

- Three trx—

a1,b1,c1—join the flush queue at virtually the same time. In this example, there are no committed trx, so the commit parent,< >, is empty. One of these threads is leader; it doesn’t matter which. The leader flushes all three trx and moves them to the sync stage. - A new trx—

d1—enters the flush stage, but the first three trx didn’t wait long enough so they’re already syncing (d1can’t join them in the group commit). - The first three trx move to the commit stage and finish in InnoDB, releasing locks.

Trx

d1moves to the sync stage and syncs alone. - Two new trx—

e1,c2—enter the flush stage. Sincec1just finished committing, the new trx havec1as their commit parent. Trxc2is the second instance of thectrx. Consequently,c2had to wait forc1to commit (and release its locks) because the two acquire the same locks. In this case,c1is truly the commit parent ofc2. However, trxe1doesn’t conflict withc1orc2; it just happens to commit at this time whenc1is the max committed trx. Trxd1finishes committing. - Trx

e1, c2proceed through the sync stage. - Trx

e1, c2proceed through the commit stage.

As mentioned earlier, MySQL always group commits when possible:

- When both BGC sysvars are zero, group commits are possible when threads pile up in the sync queue either by good luck (they arrive in the queue at virtually the same time) or bad luck (the leader thread has stalled for some reason)

- When either BGC sysvars is non-zero, it enables a sync queue wait that makes group commits more likely (and larger), but it incurs a penalty: the trx commit process is slower

Here’s the same example but with a sync queue wait:

t| FLUSH | SYNC (with delay) | COMMIT

-----------------------------------------------------------------

1| < >a1, b1, c1 | |

2| < >d1 | < >a1, b1, c1 |

3| < >e1 | < >a1, b1, c1, d1 |

4| | < >a1, b1, c1, d1, e1 |

5| | | < >a1, b1, c1, d1, e1

6| <e1> c2 | |

The example above is the same as the one above it, but this time there’s a sync queue wait that allows trx d1 and e1 to join the group commit in the sync stage.

However, since trx c2 still conflicts with c1, c2 cannot enter the prepare phase (before BGC) until c1 is done committing and has released its locks.

But once c1 has committed, then c2 prepares and begins BGC at t=6 with e1 as its commit parent.

Locking Interval

In the example above, trx a1, b1, c1, d1, e1 can execute in parallel on a replica because they don’t have conflicting locking intervals:

the locking interval for multi-statement transactions begins at the end of the last statement before commit.

Recall “statement commits” from the trx commit process: 2PC code is called after every statement. And recall from diagram 1 that the commit parent is fetched in the prepare phase. This means the locking interval spans from the last statement commit to the end of the trx commit.

If a query is not the last one in the transaction (MySQL doesn’t know how many queries a trx will contain), it will prepare (begin locking interval) but not commit. Eventually, the trx will commit and—just before storage engine commit—end the locking interval.

To understand why locking intervals are critically important for MTR, consider this informal deduction:

- When a transaction commits, it must hold all the locks that it needed to execute because locks are held until

COMMITorROLLBACK. And this must be true because, if the single-threaded client executing the transaction is able to executeCOMMIT, then it cannot be waiting or blocked on anything else. If it were, then it couldn’t executeCOMMIT, which would be a logical contradiction that proves the point—reductio ad absurdum. - Given 1, transactions that commit together hold locks that do not conflict. Imagine that transaction A holds a lock on primary key (PK) value 1, and transaction B holds a lock on PK value 2. Presuming no foreign keys, the rows corresponding to these PK value are independent from the database point of view at this “time”. Later, theses transactions might conflict (the same query can lock different rows), but right “now” they’re independent. (How “time” and “now” work are explained next: Logical Clock.) Relative to one another, executing independent (non-conflicting) transactions will not produce inconsistent data. And as long as the database remains consistent (ACID), it’s permitted.

- Given 1 and 2, transactions that commit together on a source can execute in parallel on a replica because doing so will not produce inconsistent data on the replica.

If MySQL tracks locking intervals and encodes the information in the binary logs, then a replica can determine if and when transactions can execute in parallel.

The general term for this is transaction dependency tracking, and MySQL uses two methods: COMMIT_ORDER and WRITESET.

Both are based on a logical clock—you’ll learn why later.

The following sysvars related to transaction dependency tracking were removed in MySQL 8.4:

binlog_transaction_dependency_trackingtransaction_write_set_extraction

replica_parallel_type is deprecated and will be removed in a future version.

The future non-configurable values will be WRITESET, XXHASH64, and LOGICAL_CLOCK respectively.

If using MySQL 8.x, configure these values, then be prepared to remove the sysvars when you upgrade to 8.4 or 9.x.MySQL writes two values from the trx commit process into the binary logs for each trx: <last_committed, sequence_number>.

These numbers, which result from locking intervals and commit order, are the logical clock that power MTR.

Logical Clock

In oversimplified terms, a logical clock is a monotonically increasing counter. Start at 1, step it, now it’s 2. Step it again, now it’s 3. And so on. This is an oversimplification of an important concept, but I’ll just focus on MySQL.

MySQL uses a logical clock and commit order for transaction dependency tracking. (It also uses writesets, but more on that later.) The logical clock counts transaction as they’re written into the binary logs during the trx commit process.

Transaction dependency tracking determines if transactions can execute in parallel. Logical clock determines when transactions can execute in parallel, if they can.

One trx can depend on another for different reasons. The most common reason is conflicting locking intervals or writesets. But there are other reasons (like DDL statements) that cause transaction dependencies. For simplicity, this page use "depends" and "conflicts" synonymously because the end result is the same: dependent or conflicting trx cannot execute in parallel.

If trx 5 depends on trx 4, then the two cannot execute in parallel; a replica must execute trx 4 before trx 5. (Of course, logical clock time 4 is before 5.) But if trx 5 does not depend on trx 4, then a replica can execute trx 4 and 5 in any order: 4 then 5, 5 then 4, or 4 and 5 at the same (logical or wall-clock) time.

The sooner a trx can execute the better because “perfect parallelization” would mean all trx are non-conflicting (independent) and can execute now—at the same time. But that’s neither the norm nor the expectation; rather, it’s expected that some trx can execute at the same time, but others have to wait.

If, for example, the trx in question is sequence_number = 16, can it execute in parallel with trx 1–15?

Or will it have to wait until the logical clock reaches 16?

The answer with logical clock v1 was pretty simple. Logical clock v2, which is still current as of MySQL 9.0, provides a better answer. And writesets provide an even better answer.

v1

MySQL logical clock v1 was very short-lived (v5.7.2–v5.7.5 inclusive) and too tightly coupled to binary log group commit because it recorded only the commit parent. As such, only trx in the same group commit—with the same commit parent value—could execute in parallel. This worked but it limited parallelization (v2 and writesets will show why).

Suppose that a binary log contained:

commit_parent=0 trx 3

commit_parent=0 trx 4

commit_parent=0 trx 5 // When can this one execute?

commit_parent=3 trx 6

commit_parent=3 trx 7

With v1, trx 5 could execute in parallel only with trx 3 and 4 because these three trx had the same commit_parent value: zero.

So a replica with four applier threads would execute trx 3, 4, 5, and wait—the fourth applier thread would idle.

When all trx with commit_parent=0 were done, the replica would proceed to the next group commit parent.

Because MySQL logical clock v1 worked this way, larger group commits on the source were required for more parallelization on a replica. As such, the sysvars to tune BGC also tuned parallelization for MTR. But this is no longer true with logical clock v2 and writesets.

The BGC tuning sysvars still exist to improve the commit process (some servers still use spinning disks), but as of MySQL 8.4 they’re obsolete with respect to MTR because logical clock v2 and writeset decouple BGC size from MTR parallelization.8

(For MySQL 8.0, although deprecated as of v8.0.35, set binlog_transaction_dependency_tracking = WRITESET.)

v2

Introduced in v5.7.6 and still current in MySQL 9.0, logical clock v2 adds the transaction sequence_number to the binary logs and allows trx T to execute in parallel on a replica if the sequence_number of the oldest trx that’s executing is greater than the last_committed of T.

Consider the example from above again:

last_committed=0 sequence_number=3 // ...executing... (oldest)

last_committed=0 sequence_number=4 // ...executing...

last_committed=0 sequence_number=5 // <- T

last_committed=3 sequence_number=6 //

last_committed=3 sequence_number=7 // (newest)

Trx 3 and 4 are executing. Trx 5 can execute in parallel because 3 (the oldest executing) is greater than 0, the commit parent of 5:

| Oldest Trx Executing | Can Execute Trx 5? | |

|---|---|---|

sequence_number=3 | > | last_committed=0 |

(v1 allowed trx 5 to execute in parallel but for a different reason: same commit parent.)

As long as trx 3 is executing, trx 6 and 7 cannot execute because the check is false. But once trx 3 is done, then trx 6 and 7 pass the check:

| Oldest Trx Executing | Can Execute Trx 6 or 7? | |

|---|---|---|

sequence_number=4 | > | last_committed=3 |

The crucial difference between logical clock v1 and v2 is that that v1 did not look back in logical time. Conflicts weren’t really identified, they were avoided by parallelizing trx only in the same group commit. But v2 looks back in logical time—across group commits—to identify the soonest a trx can execute in parallel, which is after the last conflicting transaction.

“Looks back” is figurative; in technical terms, here what’s happening on both sides of replication:

- Source

- The last statement in a trx (before

COMMIT) gets the max committed trx sequence number. This becomes thelast_committedvalue of the trx, paired with itssequence_number—both set during the flush stage and recorded in the binary logs. (See diagram 1.) In this sense, each trx looks back when it fetches the max committed value because that value was set by earlier transactions in the commit stage. The purpose is not to identify group commits but rather locking intervals: when a trx enters the prepare phase, its locks cannot conflict with the last committed trx (else it wouldn’t have been able to enter the prepare phase). - Replica

- For each trx, a replica preforms the check previously stated: trx

Tcan execute in parallel if thesequence_numberof the oldest trx that’s executing is greater than thelast_committedofT. In this sense, a replica looks back to check the oldest trx that’s still running. Again, it’s not a matter of group commit, it’s a matter of locking intervals.

Logical clock v2 is pretty good but writesets are better because they allow MySQL to look even further back in logical time by determining conflicts more precisely.

last_committed=1 sequence_number=14 <= trx 1 committed aloneI'm pretty sure that's wrong: trx 1–13 committed together because they have the same commit parent:

last_committed=0.Also, the statement "if you want the replica to apply transactions in parallel, there must be group commits on the primary" is not accurate because, with MySQL logical clock v2 and writesets, it's possible for transactions with different commit parents to execute in parallel. As such, there can be parallelization even if every transaction commits alone.

Writeset

Writeset tracks which rows each transaction changes. Transactions that change different rows are non-conflicting and can execute in parallel on a replica.

Writeset is not a logical clock but, in MySQL, it is built on top of logical clock (v2).

It tries to minimize the commit parent value; the writeset code is literally a min function:9

commit_parent = std::min(last_parent, commit_parent);

Of course, the full writeset code is more complicated, but in essence it tries to find an older commit parent by comparing rows changed (writesets).

Consider five transactions with a more complicated series of commit parents:

last_committed=20 sequence_number=21 // (oldest)

last_committed=20 sequence_number=22 //

last_committed=22 sequence_number=23 //

last_committed=23 sequence_number=24 //

last_committed=23 sequence_number=25 // <- T (newest)

When can trx 25, the newest, execute?

By logical clock alone, 25 needs to wait for 23 because last_committed=23.

And 23 needs to wait for 22.

And 22 needs to wait for 20 (not shown).

And so on.

But what if these five trx update completely different rows—no conflicts at all—and the commit parents are just arbitrary artifacts of the group commit process? 🤔

Writeset will detect this and minimize the commit parent of trx 25 to the oldest non-conflicting transaction (within certain limits). With an older commit parent, trx 25 can execute in parallel a lot sooner.

If you’re thinking “Writeset doesn’t need group commit or commit parents”, you’re right.

I wonder if it even needs sequence_number because transactions can be identified by an existing value: GTID.

But as of MySQL 9.0, the code for binary log group commit, logical clock, and writeset are still intertwined.

Writeset is great for multi-threaded replication because it identifies much more parallelization than commit order. But with parallelization comes another consideration called replica preserve commit order (RPCO), which is the focus of part 2 of this series.

J-F talks about this: it’s not easy tuning group commit and/or measuring the effects on parallel/multi-threaded replication. We need new, better metrics. As of this writing, it’s still a process of trial and error. ↩︎

However, on MySQL 8.0 if you don’t explicitly configure

binlog_transaction_dependency_tracking = WRITESET, then BGC size affects max committed values, which becomelast_committedvalues, which affect when a replica can execute a trx in parallel. But see System Variables Removed. ↩︎“Handlerton” is MySQL lingo for “handler” plus “singleton”: a single instance of code that handles (implements) a storage engine. ↩︎

Much worse than “statement commit” is the variable in MySQL source code to signal trx or statement commit:

all. If true, it’s a trx commit; else it’s a statement commit. ↩︎See MySQL 8.0: New Lock free, scalable WAL design and comment “The idea in InnoDB’s group commit is…” in function

trx_commit_in_memoryofstorage/innobase/trx/trx0trx.cc. ↩︎There used to be a wait (

binlog_max_flush_queue_time) but it was removed in MySQL 5.7. ↩︎This might be an easily fixed inefficiency in the logical clock: set the max seq once. ↩︎

Transaction dependency tracking still happens during the BGC process; but with writeset, BGC size no longer limits or determines MTR parallelization. ↩︎

sql/rpl_trx_tracking.ccWriteset_trx_dependency_tracker::get_dependency↩︎

Copyright 2025 Daniel Nichter