How to Write Well

I wrote this page before reading On Writing Well by William Zinsser.

To my surprise and delight, he reinforces everything I wrote below. In fact, he goes further and makes the points stronger. For example, near the end of the book he writes:

No writing decision is too small to be worth a large expenditure of time.

Zinsser is (or was: he died in 2015) an authority on writing, and I’m just an amateur by comparison. So I strongly encourage you to read his book because it’s amazing and flawless from the very first word to the very last word. There are several chapters I was going to skip because they seemed irrelevant to me (like writing about sports), but I gave them a chance and every time—every chapter—surprised me with its insights. Read On Writing Well front to cover and you’ll learn a tremendous amount about writing well.

But if you want the TL;DR of the book, this page provides one. Just remember: I’m being easy and generous here (compared to Zinsser) because my intended audience is engineers who are trying to engineer, not write.

This guide is intended for engineers writing technical documents. Most of it does not apply to other audiences or purposes. For example, it would be quite difficult (or interesting) to follow this guide when writing poetry. However, impeccable writing for any audience or purpose has, in my opinion, the same impact as poetry: it moves the reader. Perhaps, then, the only difference is that engineers write technical documents to “move” other engineers to understand and build systems. But I digress; let’s get back to the point.

The moment you need to write a technical document is the moment that writing becomes a skill for which you are responsible to execute with the same quality and professionalism as other skills. Let me state it more bluntly: if you’re a programmer and you think high-quality professional writing is not your responsibility, you are wrong. Nobody is hired only to code. I will make a sweeping generalization by claiming that communicating and “syncing” information is implicit to every career. Even the most arrogant engineer who thinks they are always right will deign to communicate their brilliance to other engineers, even if only to receive their adulation. But imagine if that arrogant engineer did not communicate well: how would their brilliance shine brightly and clearly through the linguistic muck obscuring their revelations? Alas, their poor communication might have the opposite effect: leaving other engineers to wonder “Does this person know what they’re doing?”

The preceding is dramatic but not unrealistic: I have encountered many great engineers who do not write well—some don’t even try. In my opinion, poor writing limits their potential because exceeding one’s own abilities requires “working through” other engineers, which requires aligning those engineers in thought and action. For programming, design docs (or specifications) are the primary source that align engineers. Design docs are especially important, but all written communication is important because if you take the time to write something, you presumably want others to understand and agree. To those ends—understanding and agreement—it is imperative to write well so that your words clarify and amplify your points, rather than causing readers to stumble over them.

But enough philosophy of writing—let’s dive into specific aspects of writing that are necessary for writing well.

Grammar

Learn and use grammar correctly. I suggest Grammatically Correct by Anne Stilman.

Grammar is the one aspect of a language that everyone must follow because it’s the shared foundation that makes communication possible. That doesn’t mean grammar is binary or definitive in every case (there is the “rule of cool” as my O’Reilly editors would say), but it does impose certain guidelines—the shared foundation has limits. Ignoring them precludes any semblance of professionalism. For example:

- Hyphen (-) and em dashes (—) are objectively different punctuation marks.

- There is a space before parenthetical notes (like this).

- Commas are flexible but objectively wrong in certain places.

- Proper nouns are capitalized, not random words the writer deems important.

- Acronyms are all uppercase: IDE, PCI, IEEE, RFC, SSD, HDD, LED, and so on.

I emphasize grammar as the first aspect of writing well because I routinely see engineers disregard it. Granted, grammar is a vast and complicated subject, so a few mistakes are normal (even editors disagree on the finer points of grammar), but it’s imperative that you understand and employ the basics correctly. If you’re not sure about a grammatical rule or construct, then look it up. If you can’t find an answer, then reword or restructure to avoid the questionable grammar. Simple is good (and often time betters). You don’t have to become a grammarian, but you must get the basics right.

Advanced grammar begins to bleed into style. For that, I suggest It Was the Best of Sentences, It Was the Worst of Sentences by June Casagrande.

Consistency

Define and use consistent terminology.

Engineers often write to explain complex and nuanced systems. As such, the reader already has a difficult job: understanding that complexity and nuance. If the writer does not use consistent terminology, they create a moving target for the reader, making their job unnecessarily difficult. For example, if you’re describing a system but you don’t use consistent names for its parts, then every time you reference a part by a different name, the reader has to stop, think, and hopefully realize to which part you are now referring—and that extra mental work happens before the reader can understand what you’re trying to explain. Consistent terminology avoids that extra mental work, which is good because it allows the reader to focus on what you’re communicating rather than stumbling over how you’re communicating.

The greater advantage to consistency is that it’s the foundation of a domain language: a shared set of terms and understanding of (and around) those terms. A domain language has tremendous communicative value because it acts like lossless compression of language: readers can figuratively decompress a single well-defined term into a wealth of information and understanding, which makes overall communication faster, easier, and more precise—you don’t have to repeat yourself. For example, in the domain of automobiles, when I say “engine” you know exactly what I’m referring to, what it does, and (maybe) its internal parts. That trivial bit of domain language saves both of us a lot of time by decompressing to the same general understanding in both our minds. We might have different levels of understanding, but the point is that I don’t have to describe what I mean, like “the main block with 4, 6, or 8 cylinders where the air-fuel mixture is combusted to turn the crankshaft that’s attached to the transmission.”

Although this guide is about writing, engineers must be consistent when talking, too. Not surprisingly, it’s confusing when people write one thing but say another, or vice versa.

Short and Simple

Write straight to the point; don’t hide it in a maze of words.

Humans have a tendency to ramble, repeat, and add superfluous words. Most times, the excess is an unintentional side-effect of simply being able to say a lot about the subject at hand. For example, if you’re writing a design document for a system, you obviously know a lot about the system. As a result, you “pour” knowledge onto the pages in the form of long, complex sentences.

The problem with long, complex sentences is that they require extra mental work by the reader—like inconsistent terminology. Even if the reader understands what you wrote, they may not understand what you meant. They read the words, but they don’t get the point.

I tell engineers: every sentence must punch. Please excuse the aggressive metaphor, but “punch” refers to swift and impactful. A swift sentence is either short or so elegantly worded that it reads effortlessly. An impactful sentence either makes a point clear or advances the discussion. It’s a weird metaphor, but I think it works because a long, slow punch is like a long, complex sentence: it doesn’t work well.

I’ll share with you a semi-secret writing technique to help make sentences punch: write one sentence per line. When I first learned this secret, I scoffed because I had been writing (and thinking) in paragraphs my whole life. But I gave it a try and it was a game-changer; now it’s the only way I write. (After it becomes a habit, you can return to writing in paragraphs, but your mind will continue to think sentence by sentence.) For example, here’s the Markdown source for the first paragraph of this page:

This guide is intended for engineers writing technical documents.

Most of it does _not_ apply to other audiences or purposes.

For example, it would be quite difficult (or interesting) to follow this guide when writing poetry.

However, impeccable writing for any audience or purpose has, in my opinion, the same impact as poetry: it moves the reader.

Perhaps, then, the only difference is that engineers write technical documents to "move" other engineers to understand and build systems.

But I digress; let's get back to the point.

Writing one sentence per line quickly reveals which sentences are short (and probably simple) and which are not (and probably complex). In the example above, the 3rd, 4th, and 5th sentences are obviously much longer, so it’s worth asking: are they punching? Rereading those three, I think it’s clear what point each one makes in the context of the paragraph. But if I wanted to make them more punchy, I could revise them as follows:

This guide is intended for engineers writing technical documents.

Most of it does _not_ apply to other audiences or purposes.

For example, it would be difficult to follow this guide when writing poetry.

However, impeccable writing for any audience or purpose has the same impact as poetry: it moves the reader.

Perhaps the only difference is that engineers write to "move" other engineers to understand and build systems.

But I digress; let's get back to the point.

A few words have been removed from the longest sentences, but the points of the paragraph remain. It reads more densely now, which brings me to the next point: sentence complexity and density are different. Sentence complexity means the point is hidden in a maze of words and the reader has to find it—that is bad writing. Sentence density means the point is presented directly but stated compactly, so it requires “unpacking”. For example, this is why the first sentence (and paragraph) of my book is simply:

Performance is query response time.

Those five words require 300 pages to unpack. Nothing hidden, but extremely compact.

Density and terseness often go hand in hand, but not always. Here’s another dense sentence that some of my colleagues will recognize:

Along the way, the problems of today will not be solved by happenstance or “good enough” thinking but, rather, as the result of clear alignment on the principles, values, and purposes towards which we build this new global database infrastructure.

Although that sentence is relatively long, it’s still dense because I cannot see how to state it more compactly without losing the full meaning or being cryptic.

Ironically, this explanation of “short and simple” is neither. Let me make two more points, then we’ll move on.

Presume the language is not the reader’s native language. For example, if you write in English, presume English is not your readers’ native language. This helps you to write short, simple sentences—and avoid idioms and slang.

Short and simple does not mean simplistic. Don’t write like an elementary school child. Write like a university professor, and make every sentence punch.

Formality

Err on the side of formality and professionalism.

Don’t write like you’re having a casual conversation with friends, family, or yourself. At the same time, don’t write like you’re addressing Congress (or Parliament). Write as a professional to other professionals, leaning toward formality and seriousness. Never be offensive, controversial (in a social sense, not a technical sense), or risqué—these have no place in technical writing; they only diminish your credibility and reputation. Avoid being sensational or dramatic unless the point truly warrants it. Be factual and unbiased, but don’t shy away from arguing your points professionally and respectfully.

These guidelines don’t preclude some levity, quips, or jokes. In fact, I encourage some to avoid dull or stilted writing. Just be very sparing with such informality.

Organization and Flow

There are no general guides (that I’m aware of) to determine how information should be organized in a document. Each document is different, so the common advice is to organize the document logically, but that’s not very helpful because it only moves the problem and raises another question: what’s logical? This line of thinking doesn’t bear fruit, so let’s try something else…

Organization of information within a document is not a problem that I commonly see. Plus, technical documents often have a predetermined organization (a template). (Or perhaps engineers have an innate sense of organization due to it being a fundamental aspect of programming?) Instead, the far more common problem that I see is flow: how the writing leads the reader from one topic, idea, or point to another. An analogy might help: a document is a body, how it’s organized is its skeletal structure (its bones), and its flow is the connecting tissue and joints between the bones. Organization and flow are different but connected and related, and each helps the other function.

Flow is challenging because the bits of writing that constitute flow don’t appear (at first) to be important. So why bother? Why not just state the important technical points, then abruptly change topics as needed? For that matter, why not just state everything in a bullet list?

Flow is required to connect the topics and ideas because humans use connections to understand and grasp complex systems—hence expressions like “connect the dots” and “put it all together”. Without flow, a document is disconnected information—raw material. With flow, a document becomes a body of knowledge and understanding—a working system. In my opinion, great flow is the secret behind great writing: when you read something and think “Wow this is great,” it’s a combination of great “bones” and the flow connecting them. Let’s study an example.

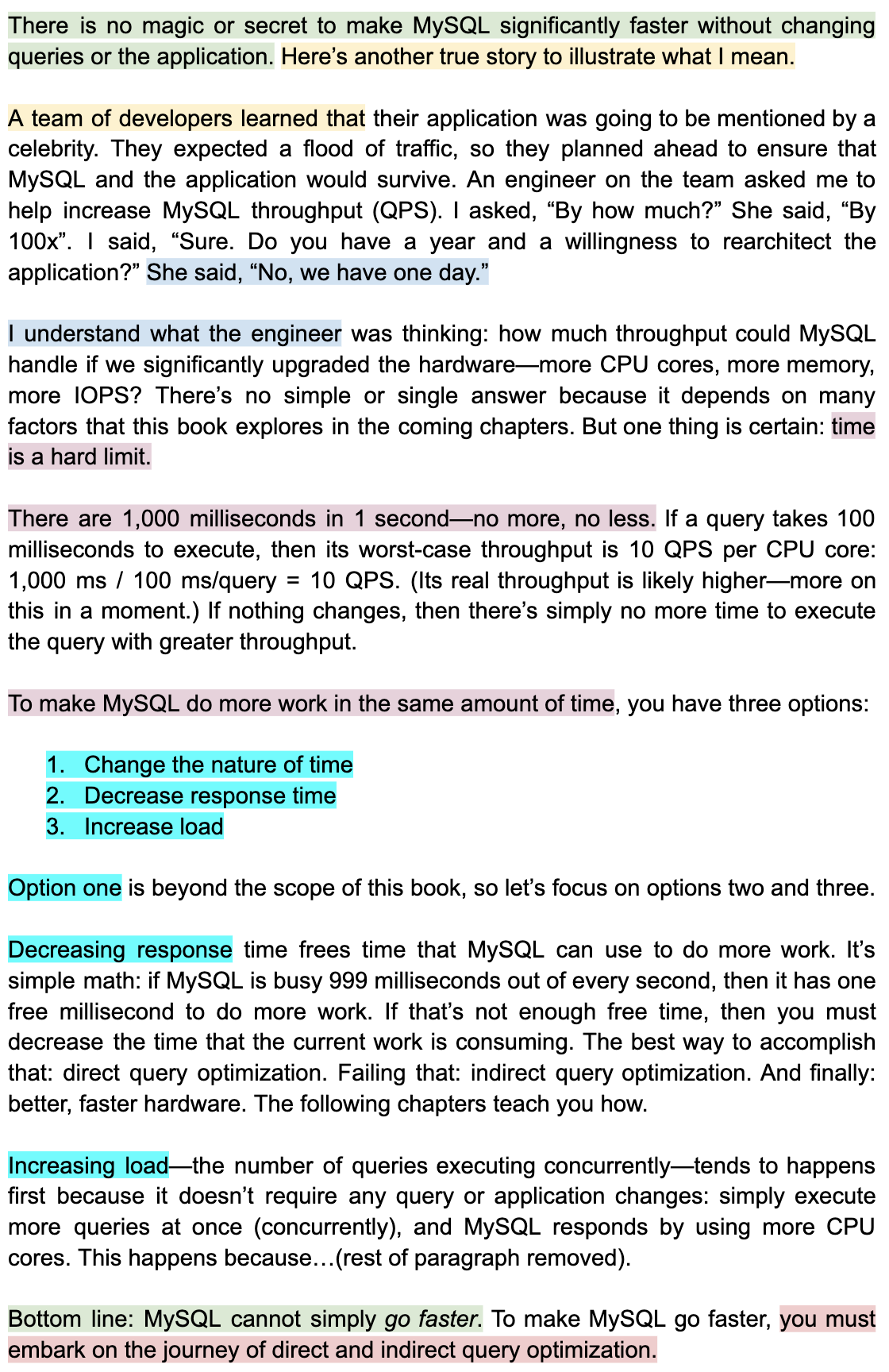

The following excerpt is a single section titled “MySQL: Go Faster” from chapter 1 of my book. I highlighted the flow, and below I explain it.

The first sentence (highlighted green) really punches: that’s the point, plain and simple—drop the mic. … But I’m writing a book, so I need to unpack that dense bit of truth. I could flow right into a technical explanation, but leading with a true story can be more captivating and interesting. The phrases highlighted yellow show how I flow from the technical point (the first sentence) to a story about it. Now the reader expects a story in the next paragraph, and that’s what they find.

When the short story ends, how can I flow back to some technical discussion? In this case, the story is a bit of a joke: the engineer wanted to scale up 100x in 1 day. So I use the punchline to flow from the second to third paragraph, highlighted light blue. Actually, the whole third paragraph is flow: it’s a gentle transition from “100x in 1 day is not possible” to “here’s the real issue”: time (highlighted light magenta.)

Paragraphs four and five explain what I mean about time being a hard limit to performance. But since it’s a book about improving performance, I can’t stop there; I have to offer solutions. In this case, I choose an abrupt but effective flow for offering solutions: a list (highlighted cyan). Then I explain each solution (each list item) in its own single paragraph, and I’m careful to start each paragraph with “Option (number)” or the exact wording used in the list to ensure the reader can easily match the two. Again, this type of flow (highlighted cyan) is abrupt, so it’s not always appropriate. There are alternative flows, but they’re out of scope for this guide. (If you publish professionally, you’ll undoubtedly discuss them with your editors.)

The final paragraph circles back to the first sentence to recapitulate the main point, which also signals to the reader that the section is complete. The last part of the last sentence (highlighted light red) flows the whole section and chapter into the next chapter because—not shown here—previous sections explain “direct and indirect query optimization” and state that chapter two addresses the former (direct query optimization).

Speaking of circling back: organization. The reason I focus on flow rather than organization is because flow determines organization. When you sit down to write a document about topics A, B, and C, you probably wonder if you should organize it like:

- A, B, C

- A, C, B

- C, B, A

Instead of grappling with organization, focus instead on the flow between the topics. You will likely find, for example, that it’s easy or natural to explain C first because that understanding leads to A, which together (C and A) forms a context for explaining B.

Flow applies at every level of organization: sections and subsections; paragraphs within each section; and sentence by sentence. Technical documents often have a predetermined organization (a template), so there’s little to no high-level flow between sections. Paragraph flow is the bulk of the work and, thus, the bulk of the challenge. (The excerpt above highlights flow between paragraphs within one section.) Work on paragraph flow first because it’s easy (or easier) yet impactful. Sentence flow is more difficult (I don’t address it in this guide), but it’s the same basic principle as paragraph flow; only the unit of work is a lot smaller: sentences.

I’ll share another semi-secret with you: professional writers work on word flow, too. At this lowest level, we’re concerned with every word, punctuation, structure, tense, mood, tone, and more. For example, I don’t use punctuation marks at random—here’s an example:

- For example, I don’t use punctuation marks at random: I choose every one with intention.

- For example, I don’t use punctuation marks at random; I choose every one with intention.

- For example, I don’t use punctuation marks at random—I choose every one with intention.

All three variations are grammatically correct, but which one would I have chosen if I had not instead chosen to make an example of it? We’ll never know… But I do know this: if you publish professionally, you will discuss word flow with your editors.

Avoid

So far I’ve been focusing on what to do to write well. For a fun little break, let’s look at what not to do. I highly suggest avoiding the following in professional technical writing. Not only does avoiding the following help make each sentence punch, it also enhances technical accuracy.

Idioms and Slang

“The server bit the dust.” That statement employs an idiom: bite the dust. I bet there’s only a 50% chance that non-native English speakers understand that idiom. Even if the other 50% figure out the meaning from context, it’s an unnecessary distraction, especially when (as the writer) you could have easily written “The server failed.” Avoid idioms in professional technical writing because they don’t add technical clarity, and there’s a high probability that some readers won’t understand them.

“The load was crazy.” That statement uses slang: crazy as in very high. Slang has the same problem as idioms: it doesn’t add technical clarity, and there’s a high probability that some readers won’t understand it.

Let me also take a moment to point out that non-native language speakers probably use a dictionary, but some dictionaries do not include or indicate slang, idioms, or vulgar language. For example, I have seen a dictionary that doesn’t mention that “shit” is vulgar. Not surprisingly, the person using that dictionary used to say “dog shit” in polite company rather than something more acceptable like “dog poop”.

Adjectives, Adverbs, and Superlatives

You were probably taught to use adjectives and adverbs because they enhance and sometimes clarify nouns and verbs. For example, a “lit room” is markedly different than a “dimly lit room”—thank you adverbs. But the purpose of technical writing is technical clarity and correctness, not literary pizazz. Therefore, you should avoid adjectives, adverbs, and superlatives that do not enhance technical clarity or correctness. (If you really want to add pizazz, limit it to nontechnical sections and paragraphs, like backgrounds and general introductions.) Let’s study three examples.

| With Adjective | Technical Rewrite |

|---|---|

| The database is slow. | Given the current hardware and application workload, P99 response times are higher than the SLO. |

| Heavy load brought down the application. | A 10x increase in user activity exhausted connection pools, which brought down the application. |

| The design is easy to understand. | (See Vacuous Phrases.) |

As a DBA, the first example is common and important to me: what does “slow” mean? How slow? What part of the database is slow? How are you measuring or reporting “slow”? Slow where or doing what? “Slow” has no precise meaning in this context. The statement is hardly better than “The database is a turtle.” Of course, I understand what the statement is indicating, but that’s the point: it’s not precise; it only indicates. The technical rewrite is precise: the database is “slow” because P99 response times exceed the SLO. “P99”, “response times”, and “SLO” are all precise and objective—they’re just not defined in this example. Moreover, it acknowledges that performance is a function of the application workload and current hardware, which is a very dense way of saying “The database itself is fast; what you’re asking it to do is slow.” To unpack that, read my book.

Likewise, most engineers understand “heavy load”, but does “heavy” really add technical value or clarity? It does not unless you define “heavy” in context. So avoid such adjectives in technical writing.

The final example is a (predicate) adjective that lacks any technical specificity, but more importantly it’s a vacuous phrase that I address in the next section.

Everything just said about adjectives applies even more to adverbs. For example, what does “The server crashed quietly” mean in a precise, technical sense? Most engineers probably understand how and why “quietly” is modifying “crashed”, but it’s better to be precise: “The server crashed without logging errors or triggering alerts.” Now I know exactly what you mean, and not a single adjective or adverb was used.

Superlatives are the worst. (See what I did there? Hilarious.) “Memory has the greatest impact on performance.” Really? The greatest impact? If that’s true, the document must prove it. Otherwise, it could be technically incorrect, so drop the superlative: “Memory has a significant impact on performance.” But wait: I just swapped a superlative for an adjective: significant. If you can quantify “significant”, then do it; if you cannot, then strike it: “Memory impacts performance.”

Is technical writing too dry and boring without adjectives, adverbs, or superlatives? I don’t think so, and I offer my book as proof. This guide is also proof: look at how sparingly I use adjectives, adverbs, and superlatives. If you’re not asleep yet, then I suppose we can write without these and still keep the reader engaged. If you are asleep, then I’m talking to myself, which is fine: I agree with me.

Vacuous Phrases

Human speech is littered with vacuous phrases like:

| Vacuous Phrase | Counterpoint |

|---|---|

| As you can see | Can I? Maybe, maybe not. How do you know? |

| It’s clear from/that | Is it clear? Maybe, maybe not. |

| In fact | Is it really a fact? Or do you just think it should be obvious? |

Vacuous phrases can be removed without affecting the sentence or its meaning, which is why they’re vacuous. Since technical writing communicates complex and subtle ideas, do not waste space (and the reader’s time) on vacuous phrases: write straight to the point; make every sentence punch. More importantly, vacuous phrases don’t communicate value, so we have two reasons to remove them.

Sentence Structure

Consider this grammatically correct sentence that I read recently in a design doc:

Detailed in this section are account vending and access considerations.

That sentence is short and simple but highly inverted—actually, I would say it’s reversed with respect to basic sentence structure. To see how, let’s break down its grammatical parts:

Detailed in this section | are | account vending and access considerations.

(adjective phrase) | (verb) | (subject)

The subject appears at the end, which is opposite (reverse) of the simplest sentence structure possible: “subject verb (object).” For example, “dogs bark” or “dogs eat food”. Let’s flip the sentence around:

Account vending and access considerations are detailed in this section.

Account vending and access considerations | are | detailed in this section.

(subject) | (verb) | (adjective phrase)

Now its structure is more typical, which reveals another issue: passive voice. Without going down the rabbit hole, I’ll simply point out the subject is not doing (or acting upon) anything, which is why it’s passive. Passive voice is not incorrect or bad (on the contrary: when employed intentionally and skillfully, it can be quite impactful), but it’s not ideal in technical writing because we want to be as direct as possible when describing complex systems.

Here’s the sentence completely restructured so it’s both active and punching:

This section details account vending and access considerations.

This section | details | account vending and access considerations.

(subject) | (verb) | (direct object).

Simple, straight-forward sentence structure is ideal in technical writing because, honestly, we’re not trying to write “beautifully”, we’re just trying to convey technical information as correctly and precisely as possible. Some variation in sentence structure is good, just be mindful of extreme cases. And while you’re at it, check your parallelism, too.

Present Tense

Default to the present tense; use the future tense when necessary.

Technical documents written in the future tense are surprisingly common—at least the documents that I read. But it’s understandable: engineers are thinking of the future when the system will be.

Writing in the future tense is, of course, grammatically correct, but it’s unnecessary and restrictive. It’s unnecessary for the obvious reason: because you can (and should) write in the present tense. It’s restrictive because, if everything is future tense, then how do you express a future state or action? Here are three examples: the first is what I commonly read and should be avoided; the second is a little better; and the third is best with respect to tense and sentence structure:

- The service will detect if the database is offline, and it will failover.

- When the service detects that the database is offline, it will failover.

- The service fails over when it detects that the database is offline.

The first demonstrates what should be avoided: all future tense. The second is a little better, but look carefully: it seems to begin in present tense, but it’s really an inverted future tense statement: “The service will failover when the service detects…” (“When…” is a prepositional phrase.) The third is pure present tense and exceedingly clear and direct.

Reserve future tense to describe things that are necessarily future because they depend on some antecedent condition. For example, “We will diagnose why the server caught fire after extinguishing the flames.” In this example, diagnosis must happen in the future, after the antecedent condition of putting out the flames. Or, a more mundane example: if a bug has caused data loss, then it’s fair and accurate to say “Fixing this bug will prevent further data loss.” By contrast, saying “Fixing this bug prevents data loss” is unfair and inaccurate: data has already been lost! In truth, we can prevent future data loss only in the future by fixing this bug, so the future tense is warranted.

There’s a practical reason why you should default to the present tense: eventually, the system you’re describing will exist. Once it does, present tense statements about it will continue to read well and make sense for eternity—or however long the system remains in use.

While we’re near the subject, I’ll briefly add: avoid the conditionals “would” and “could”. What does “The server could crash” really mean? Of course it could, but can it? Yes it can. Better yet, given the preceding spiel on future tense, it’s better to be specific: “The server will crash if you throw it in a lake.”

Communicate Value

Writing is easy, and writing is difficult. It’s easy to throw words on a page. It’s difficult to make every word punch.

Do the previous three sentences mean something? Yes. But do they communicate value? No.

Communicating value means that each and every sentence adds to the reader’s knowledge. (Flow notwithstanding.) Communicating value is exceptionally difficult because humans will infer value where none is present. Why? I think it’s a combination of politeness (we don’t want to tell the writer that such-and-such doesn’t communicate any value) and human nature (we actively seek and infer knowledge, especially when reading). As a result, a lot of writing is devoid of value (fault of the writer), and we don’t see or admit it (fault of the reader).

The first three sentences of this section were an intentional example. They might read nicely or have an air of insight, but let’s be honest: they didn’t add anything to your knowledge.

When writing, scrutinize each and every sentence and ask yourself: does this sentence add to the reader’s knowledge? If you’re not sure, then remove the sentence and see if the points you’re making still stand and make sense. In my opinion, great writing is a nonstop flow of punchy sentences that communicate value.

Polish

Great writing requires concerted effort and polish: rewording, restructuring, revising. It requires a lot of work.

Those statements apply to any skill, so they’re probably obvious, but I state them explicitly to end this guide on the same note that started it:

The moment you need to write a technical document is the moment that writing becomes a skill for which you are responsible to execute with the same quality and professionalism as other skills.

With effort and polish you will produce great writing.

Copyright 2024 Daniel Nichter