Approaching a New Software Project

How to start and where to go

Approaching a new software project is difficult for two reasons. First, there’s no “guiding star”, no objective starting point. The developer can begin from and proceed in many directions, which makes choosing difficult. They want to proceed in a good direction from the start, not wasting time or effort, but how can they make a good choice without a guide or the benefit of experience? Being forced to choose and move ahead, the choice is often made randomly rather than methodically. If lucky, the choice is good, but as Ryan says: “Luck is not a strategy.” Second, this is not something commonly taught. It’s common for developers to learn by being thrown into water and they either sink or swim. Becoming good at moving from idea to design to implementation to the long tail of software development/maintenance is a skill that requires practice, learning from mistakes, and learning from other resources (books, blogs, people, etc.).

This page layouts an approach for creating a new software project, from idea to implementation. The steps are given but not exhaustively described because a book is needed to fully describe each step (and books exists for each step). This is an orientation, a guide to point in you a good direction and give you a good idea of what lies ahead and how to get there.

1. Understand “user and need”

Software is always used by people. Even backend systems must be configured, deployed, maintained, monitored, and troubleshot by people. Until the AI dystopia future arrives and there’s software neither written by nor intended for humans, always begin by understanding “user and need”: the user and the need the software addresses for them. Then, always keep this understanding in mind and use it to guide all non-technical details and decisions. The goal is to make the user say (of the software), “This is awesome! This makes it so much easier!” And if the software is really awesome, it will change the way the user works and make them forget the old way of doing things. An extreme example is the iPod: once delivered, portable cassette tape and CD players where almost immediately forgotten, and the world has never gone back (except ironically).

Understanding user and need does not trump or excuse technical considerations. Or, let me put it more colorfully: never give the user a rotten log. The log might look ok from the outside, but it soon collapses because it’s rotten on the inside. For software, this means that the first version works, but it’s hell to debug, fix, maintain, enhance, etc. going forward. Too often, too much emphasis is placed on the first version, as if the game is won when the first goal is scored. It’s like Stephen Curry walking off the court after scoring his first shot. The point is: as you move ahead, don’t make deep technical sacrifices or take extreme technical shortcuts for the sake of “shipping it”.

There are books about exploring user and need, and you should read a few, but the point here is simply to say that we approach a new software project not with technical concerns and considerations, but with human concerns and considerations. Before you proceed, be sure you have a firm grasp of the user and the need the software addresses, always keep these in mind, and use them to guide all non-technical details and decisions. This is the guiding star.

2. Draft the domain model

Please read Domain-Driven Design. It’s quite comprehensive, and a complete and rigorous application of its methodology is not always required, so for now a highly distilled form of domain model is sufficient. The second step to approaching a new software project is drafting the domain model, very broadly. Specifically, developers and users need to agree on and use a domain language based on common:

- Concepts

- Terminology

- Components

The last, components, can and should be hidden from users if they’re nontechnical, but if you’re developing software for internal use (i.e. by other technical people), then we should agree on common code components, too.

Agreeing on and using a domain language based on common concepts, terms, and components allows two or more people to communicate effectively, which leads to effective execution. Imagine the opposite: if you and I are working on a new system but we don’t speak the same domain language, when I say “X doesn’t work with Y”, then you might fix Q with R because our understanding, communicated by our language, doesn’t align. This sounds extreme and silly, but it’s surprisingly common because speaking the same domain language only happens when people explicitly set out to define the language and speak it, consistently. It might seem artificial, rigid, or silly at first (perhaps even childish because adults are not used to being told what to say), but trust me: when everyone is speaking the same domain language, it’s like every person on a crew team rowing in perfect synchrony: fast, efficient, beautiful.

For example, for one of my team’s projects, I can say “The CDC poller is a singelton that multiplexes events to all feeds”. That’s highly specific “domain speak” that conveys a wealth of shared understanding in the team. That kind of precise and subtle complexity doesn’t happen by accident. We intentionally built the domain language to make talking about the system fast and efficient.

Drafting the domain model is often done hand-in-hand with understanding user and need. So don’t be surprised if you switch back and forth between these two steps. In fact, user and need and the domain model must align because the domain model is really just a more precise, semi-technical description of user and need.

With respect to code components: this is often done a little later, but for now begin with very broad ideas about what kind of components will compose the new system. Is it an API, or command-line tool, or web app? Authentication? Data stores? Caches? Logging? Components to process logic? Interaction with external systems? In other words: what game are we playing? Basketball? Football? American or actual football? etc.

3. Imagine the user experience

You‘ve got to start with the customer experience and work backwards to the technology.

This is critically important. We might even make this step 2 instead of 3. (I don’t think it can be step 1 because until you understand user and need, there’s no “customer experience” to imagine.) Understanding user and need and having a domain model gives us guide lines and building blocks to begin imaging the user experience.

Developers often begin with the code, the technology, and imagine how it can be made to address the user’s need. This is not surprising and somewhat natural because they’re developers and code is what they do. However, this is like building a house then designing the house, or designing the house while building it. Also, engineers can feel like they’re not doing their job if they’re not writing code. But heed the words of Steve Jobs in this case: begin with the user experience, then work backwards to the technology.

What does this mean in practice? It means we envision how the new system will work, which depends on the type of system. For a new command line tool, for example, I begin by doing mock command and response using just plain ‘ol text:

$ es host.hostname,env app=foo,env=production

host1,production

host2,production

$ es --delete host host1

OK, deleted host1

$ es --delete host host1

OK, deleted host1 but it did not exist

# exit 0, printed to stdout

$ es --delete host host1 --strict

host1 does not exist

# exit 1, printed to stderr because of --strict

In the example above, I’m exploring the user experience on the command line with the tool (es) by simply typing out mock commands and responses, making notes like “exit 0, printed to stdout”. For an API, I’ll make a list of endpoints, data in (PUT/POST), data out/response, HTTP status codes, etc. I’ll write out the protocol and imagine using it with the API. For a web app, I’ll use a tool like Balsamiq to sketch out the UI and imagine how the user will click through and interact with UI elements, how the app transitions from various states, etc. In short, imagine all the basic, common, major interactions between user and system, write and sketch and do mocks, but not code at this point.

Does this feel like a waste of time? or “big upfront design”? It’s not. First of all, it’s super easy to change, and it gives you something to show users and ask, “Like this?” If the user says, “Yeah, like that”, then great, but you might also get a response like, “Oh no, that’s not what I had in mind at all.” Until you show the user something, you and they will never know. Second, if you have no idea what the experience will be like, then you risk wasting time, having to re-do the experience and the underlying code. Third, these mock experiences are not written in stone; they’re merely guides and should be continually refined. Even literal guiding stars (i.e. in the sky) change position slightly.

Finally: make it wonderful. Your life and your time are too valuable to spend making “eh”, so-so, mediocre software. It takes time and several iterations to refine a wonderful user experience. Don’t over-engineer or use gold plating; keep it as simple and elegant as necessary to address the user’s need. Of course, this is all easier said than done, but by imagining, drafting, and refining the user experience, you will make a wonderful one.

So, before you write code, imagine the user experience and know how, “on paper”, the new system will work, and make it wonderful!

4. Design the major components

The previous steps aim our programming efforts; they establish the target and put our sights squarely on it. When we can see clearly what we’re aiming at, hitting the target is easier, and the focus keeps us on target along the way. At this point, we begin to clarify the major, high-level components of the new system. This varies depending on what the new system is and does. For a small, simple command line tool, there may be little to no major components. But for large, distributed real-time systems, the number of components is usually numerous.

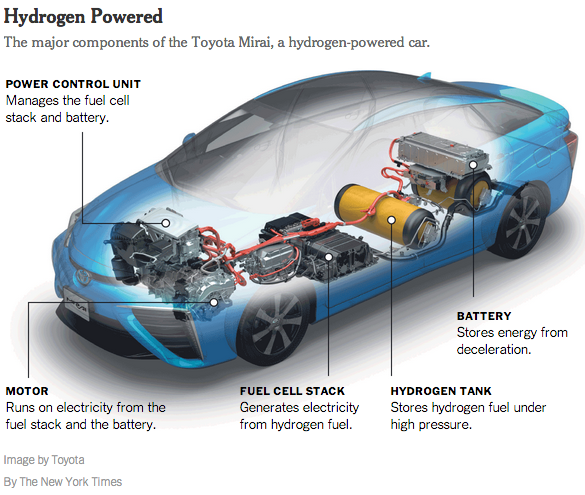

This isn’t an article about how to design components (but see other pages about software design), so the point here is only: think of the system in terms of components, knowing what each component does and why it’s necessary. There’s more art than science to this, but let me use the analogy of a car. A car has many high-level components:

You understand what a car is, how to use it, and in general how it works. From an engineering point of view, the only way to design, implement, and maintain a car is component by component because it’s too complex to do otherwise. Software systems are the same, when well designed. Don’t attempt to wrap your mind around the entire system, break it down into necessary components.

Every component should be:

- Necessary

- Well bounded/delineated

- As simple as possible, but not simpler

These three aspects are deceptively simple, and “necessary” is highly subjective because there are many ways to break down a system into components. That’s where the other two aspects help. The simpler, more well-bounded component is usually the better one. Again, this isn’t an article about designing components, but I encourage you to think about the components of a car. Physical systems don’t have the luxury of software: code is free, so we often unintentionally write a bunch of unnecessary, poorly-bounded, accidentally complex code. It works, strictly speaking, but it could be a lot better and still work. Physical systems don’t have this luxury because every piece, no matter how tiny, costs money, must be fabricated, given a part number, meet specifications (don’t want the lug nuts holding the wheels on to come off!), etc. Physical systems are driven by economic (and sometimes physical/chemical/electrical) limitations to their “purest form”. Software can and should be the same way, imho, but we have to limit ourselves by rigorously examining the necessity, delineation, and simplicity of each component we design, which leads to the next step…

5. Run the mental models

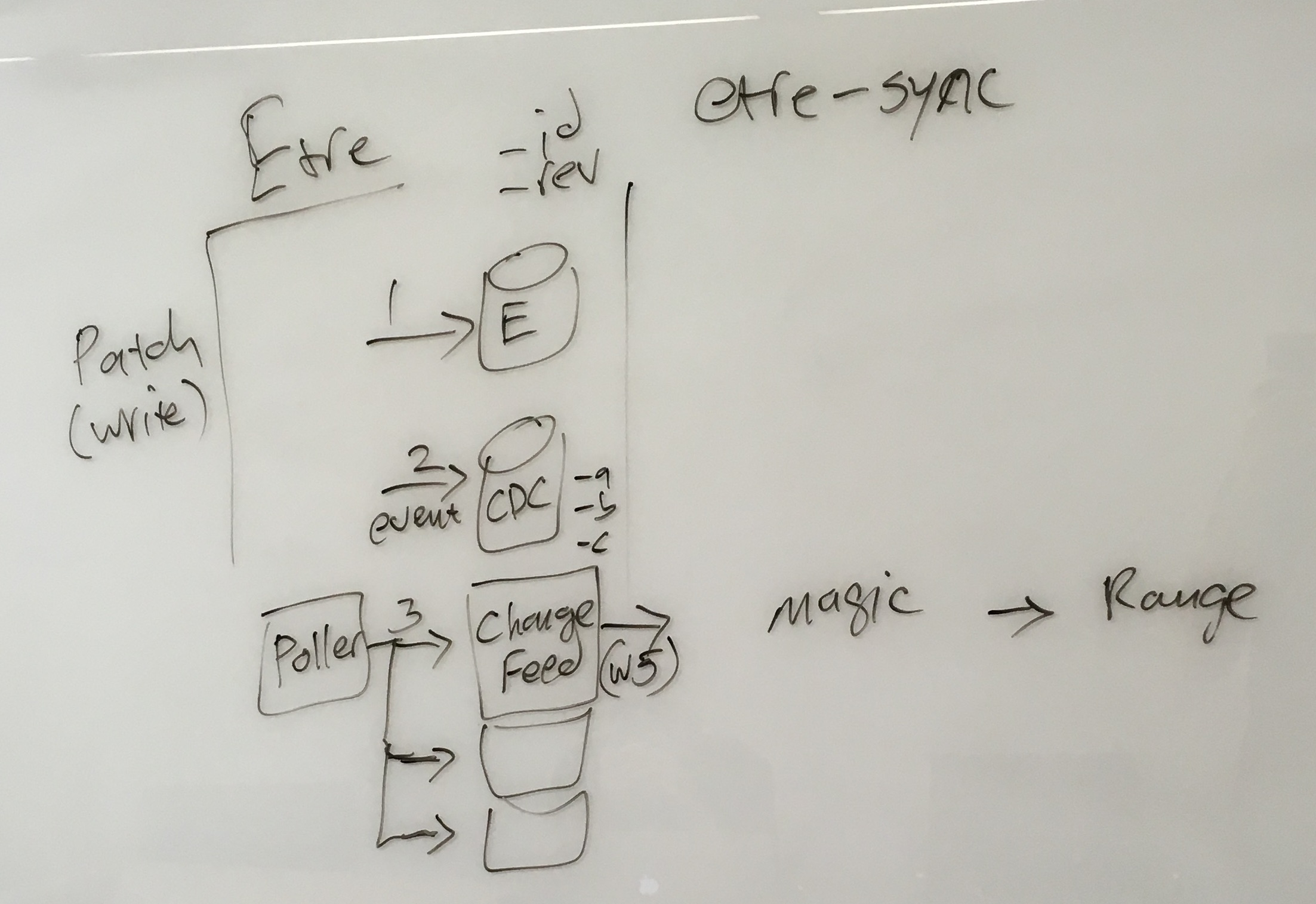

No one designs all the right components on the first try. After you have a reasonably good understanding of the needed components, start running mental models of the system in action. For example, on a whiteboard, draw the components as boxes or whatever, and then trace common usage of the system works from end to end through each component. Below is a real example from my team working on a part Etre.

The left side is Etre. The Right side is an internal system called “etre-sync” which consumes the Etre change data capture (CDC) feed. We were running a mental model of how that change feed works. It flows roughly from top to bottom, as numbered. First, the patch/write is written to “E”, the entity store (the main database of the system). Then a CDC event is written to the CDC store. Then (3) the poller picks up those events and multiplexes them to all the change feeds (one per connected client). A client (etre-sync for us) does whatever magic it wants with the event, and finally syncs to another internal system called Range.

“Whiteboard design” like this is pretty common, but how and why we use it in this approach is less common. We’re not really designing the system at this point, we’re running mental models (or “whiteboard models”) of all the previous work/steps to see if it makes sense, if it works on paper, if a component is missing or unnecessary or not clearly delineated. We do this frequently, and every time we discover something wrong, missing, or a better way of doing things. Then we go back to previous steps, update, and try the mental models again. Eventually we reach a point where every component seems necessary, well-delineated, and as simple as possible; then we know we’re ready to begin implementing the components.

6. Implement the components

This is the easiest step because it’s where developers tend to start. But in this approach, we have a lot more insight and guidance than what a developer has when staring here; we have:

- An understanding of the user and need

- A vision for the end user experience, how the software will look and feel when being used

- A vetted list of components that comprise the system

- A common, shared domain language to quickly and efficiently describe and talk about everything

With all that, my experience has been that implementation, “putting code to paper”, is quick, easy, and yields high-quality, well-tested code. It’s not uncommon to find that most components are trivial, and only a few require deeper exploration of how to implement them correctly and efficiently. In the example above, the CDC component is necessary, well-bounded, and as simple as possible, but it’s implementation is a real programming challenge (data feeds done well aren’t easy). Being well-bounded, the person who implemented the component was able to focus their attention and efforts, forget about everything else in the system, and he delivered a great CDC component that plugged right into everything else according to design and mental models and “Just Worked”.

7. Repeat

The last step leads back to the first: repeat the whole approach. Not once or twice or any finite number of times, but continue repeating the approach. Keep in touch with the user, see if anything has changed. Keep refining the domain model. Keep trying to make the user experience better, easier, more magical. And with respect to the components: keep reviewing them, challenging them, running them through mental models, and refactoring as necessary. Eventually, most components will settle into place and become very stable. But most systems have components that are a little rough around the edges, feel a little unnecessary (or, like they can/should be implemented differently, better), etc. Software is a living entity. It should always be undergoing small, iterative changes.

This is an important lesson: the mark of great software is not stasis but continual evolution and refinement. If you design a system that works, and then a better user experience or a simpler number or implementation of components is thought of, be happy: if a developer wants to change the system, it means the system is well-designed and a pleasure to work with.

Summary

All this only scratches the surface. This approach is not an extensive writeup of its steps but an orientation, a guide to point in you a good direction and give you a good idea of what lies ahead and how to get there. In summary:

- First and foremost: understand the user and the need the software is addressing, always keep these in mind, and use them to guide all non-technical details and decisions

- Draft and continually refine the domain model/language based on common concepts, terminology, and components

- “You’ve got to start with the customer experience and work backwards to the technology.” —Steve Jobs

- Design the major, high-level components of the system (analogous to the major components of a car)

- Run mental models, use a whiteboard, to see how the system works and flows with the components

- Implement the components in code

- Repeat, refine, refactor, keep improving at each step

Bonus: 8. “Ship it!” It’s a common saying because even the best approach and the best developers need a gentle nudge to deliver the new system at some reasonable point that’s almost always less than 100% done. There are no simple rules for when a system is ready to ship, but one approach is to have other pragmatic engineers, who haven’t developed the system, evaluate and decide if it’s good enough because their minds are free of all the todos and shortcomings; they only see a product that’s useful or not. If they say, “Yeah, good enough for now. Ship it!”, then do it. At this point, so much good design and implementation has gone into the system that inevitable bugs, issues, etc. will only enhance and refine the system.

Copyright 2025 Daniel Nichter