Mining the MySQL Performance Schema for Transactions

Chapter 8

The MySQL Performance Schema is a gold mine of valuable data. Among the many nuggets you can extract from it is an historical report of transactions: how long a transaction took to execute, what queries were executed in it (with query metrics), and idle time between queries. Mining this information is not trivial, but it’s fun and this blog post shows how to start.

This blog post is the ninth of eleven: one for the preface and ten for each chapter of my book Efficient MySQL Performance. The full list is tags/efficient-mysql-performance.

Queries vs. Transactions

First, why care about transactions rather than queries? After all, performance is query response time. While that’s true, and query response time is the North Star of MySQL performance, transactions are units of work with respect to the application.

For example, an app might have a multi-statement transaction to update a user profile. From the app point of view, “update user profile” is a single logical event (that comprises multiple statements). Therefore, it’s useful knowing and analyzing the response time of that event—the transaction. (It’s throughput and other metrics are also useful to know, but we’ll stick to response time for simplicity.) Moreover, as we’ll see later in this blog post, transaction response time is not the sum of its constituent query response times. The event hierarchy begins to explain why.

Event Hierarchy

transactions

└── statements

└── stages

└── waits

To quote the MySQL manual:

The Performance Schema monitors server events. An “event” is anything the server does that takes time and has been instrumented so that timing information can be collected. In general, an event could be a function call, a wait for the operating system, a stage of an SQL statement execution such as parsing or sorting, or an entire statement or group of statements.

MySQL organizes events into the hierarchy shown above. Practically speaking, every event is a transaction. Transactions contain statements, which are usually queries, but not always. Statements have various stages of execution: parse SQL, open tables, execute, and so on. And last but not least, stages incur waits, like waiting for disk I/O or the client.

This brief introduction to events and the event hierarchy is why chapter 8 of Efficient MySQL Performance begins with:

MySQL has non-transactional storage engines, like MyISAM, but InnoDB is the default and the presumptive norm. Therefore, practically speaking, every MySQL query executes in a transaction by default, even a single SELECT statement.

To inspect transactions, you must descend into the event hierarchy and its various tables. The Performance Schema is vast, so I cannot cover it in a simple blog post. At the very least, read:

- 27.9 Performance Schema Tables for Current and Historical Events.

- 27.12 Performance Schema Table Descriptions

- 27.12.1 Performance Schema Table Reference

Those three pages will give you a lay of the land.

Apart from that, it’s important to know that every event has an event ID that is a monotonically increasing integer value per thread.

So the primary key of event tables is usually (thread_id, event_id).

And since events are organized in a hierarchy, most event tables have columns end_event_id, nesting_event_id, and nesting_event_type.

This allows us to mine the Performance Schema for transactions by joining all events nested under a given transaction event ID.

I don't discuss how to setup or configure the Performance Schema in this blog post. For the examples below, I have enabled most instruments to produce a full example, but such extensive instrumentation is probably not a good idea on a busy production server.

Inspecting a Transaction

For the following example, I’m using table elem that’s used throughout my book; you can download it at https://github.com/efficient-mysql-performance/examples.

The transaction is super simple:

BEGIN;

SELECT * FROM TABLE elem;

DELETE FROM elem WHERE id=10;

COMMIT;

I typed those four queries manually, which is an important detail that we’ll see later.

But those four queries aren’t the focus; the transaction is the focus and the goal is to extract all events from the Performance Schema, thereby reconstituting the entire transaction after it has committed.

Easier said than done.

I’m going to present this example two ways. First as “raw ore”: raw queries and output from the related Performance Schema tables. Like raw ore, this data needs to be refined to be useful. Second as “ingots”: the raw data refined into color-coded groups of related events so it’s easier to inspect the transaction from start to finish.

Raw Ore

Transaction

First we extract the transaction (the top of the hierarchy):

SELECT

thread_id, event_id, end_event_id, event_name, nesting_event_id, nesting_event_type,

ROUND(timer_wait/1000000) t

FROM

events_transactions_history

WHERE

autocommit='NO';

+-----------+----------+--------------+-------------+------------------+--------------------+---------+

| thread_id | event_id | end_event_id | event_name | NESTING_EVENT_ID | NESTING_EVENT_TYPE | t |

+-----------+----------+--------------+-------------+------------------+--------------------+---------+

| 1 | 123 | 126 | transaction | NULL | NULL | 26 |

| 54 | 233 | 281 | transaction | 229 | STATEMENT | 7729078 |

+-----------+----------+--------------+-------------+------------------+--------------------+---------+

Thread ID 1 is the main MySQL thread, so ignore that.

Our thread ID is 54, and that’s important: we only want nested events where thread_id=54.

The autocommit='NO' predicate is also important: MySQL autocommit is on by default.

A single SELECT with autocommit enabled is an implicit transaction: the user (or app) didn’t explicitly execute BEGIN or START TRANSACTION.

As such, implicit transactions are usually single statements (queries).

But what we really want to inspect is explicit multi-statement transactions, like this example.

Therefore, we have to filter where autocommit='NO'.

Note, however, that even with autocommit enabled, the following explicit transaction is possible but wasteful:

BEGIN;

-- One query

COMMIT;

I say that’s wasteful because the BEGIN and COMMIT are two wasted round trips when autocommit is enabled.

Surprisingly, I see some ORMs do exactly that, but that’s a topic for next month when I cover chapter 9 titled “Other Challenges.”

Scroll right on the output and notice t | 7729078: the transaction took 7.7s to execute.

(The query converts the time from picoseconds to microseconds.)

Of course, MySQL didn’t execute any of the four statements that slowly.

As I hinted at earlier in this blog post, the transaction time is due to idle time between statements because I typed the queries manually one by one.

Idle time between statements in a transaction is one of the most important reasons to inspect transactions. Transaction idle time does not show up in query analysis because it’s not a property of any query, it’s time between queries. So although query analysis cannot reveal it, the application (and users) will experience it. Why does transaction idle time occur? Read section “Common Problems” in chapter 8 of Efficient MySQL Performance.

Notice NESTING_EVENT_TYPE | STATEMENT in the output.

That means the transaction is nested in/under a statement event, which contradicts the event hierarchy.

The full explanation is complicated (and documented in the MySQL manual); the short answer is: the BEGIN statement occurs first and creates the transaction.

The end_event_id is important because it allows us to query the nested tables efficiently: using only the primary key on (thread_id, event_id).

We know the thread ID: 54.

And since event IDs are monotonically increasing per thread, we know that all nested events must be between 229 (the BEGIN that created the transaction) and 281 (the transaction end_event_id).

Now we’re ready to query the next level down in the hierarchy: statements.

Statements

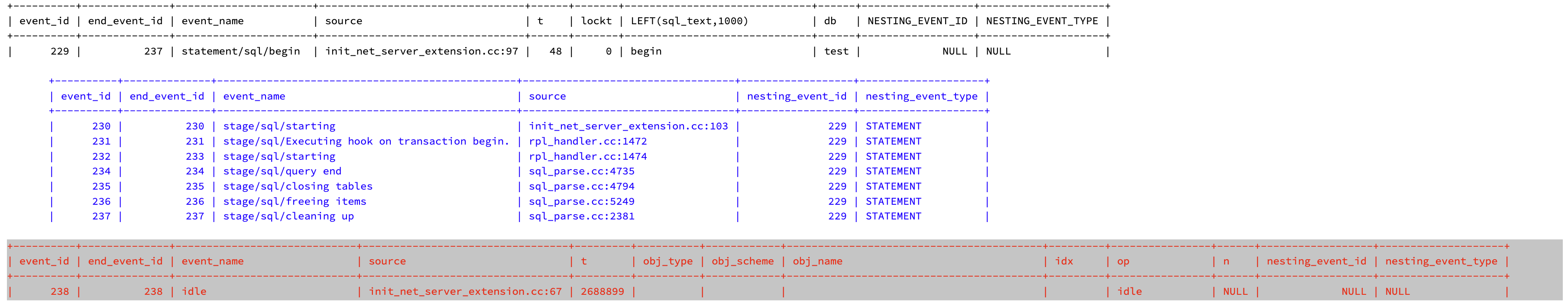

Then we extract the statements within the transaction:

SELECT

event_id, end_event_id, event_name, source,

ROUND(timer_wait/1000000) t,

ROUND(lock_time/1000000) lockt,

LEFT(sql_text,1000),

COALESCE(current_schema,'') db,

nesting_event_id, nesting_event_type

FROM

events_statements_history

WHERE

thread_id=54

AND event_id BETWEEN 229 and 281;

+----------+--------------+----------------------+---------------------------------+------+-------+------------------------------+------+------------------+--------------------+

| event_id | end_event_id | event_name | source | t | lockt | LEFT(sql_text,1000) | db | NESTING_EVENT_ID | NESTING_EVENT_TYPE |

+----------+--------------+----------------------+---------------------------------+------+-------+------------------------------+------+------------------+--------------------+

| 229 | 237 | statement/sql/begin | init_net_server_extension.cc:97 | 48 | 0 | begin | test | NULL | NULL |

| 239 | 258 | statement/sql/select | init_net_server_extension.cc:97 | 226 | 2 | select * from elem | test | 233 | TRANSACTION |

| 260 | 275 | statement/sql/delete | init_net_server_extension.cc:97 | 303 | 2 | delete from elem where id=10 | test | 233 | TRANSACTION |

| 277 | 285 | statement/sql/commit | init_net_server_extension.cc:97 | 750 | 0 | commit | test | 233 | TRANSACTION |

+----------+--------------+----------------------+---------------------------------+------+-------+------------------------------+------+------------------+--------------------+

Notice the WHERE clause: by thread ID and range of beginning and ending event IDs as explained above.

As expected, we extract the four SQL statements of the transaction.

Column t in the output is query execution time in microseconds.

The full range of query metrics is available in the table (events_statements_history), just not shown here for brevity.

Also as expected, each query was fast: less than 1 millisecond.

Total query execution time is 1.3 milliseconds, which is dramatically less than 7.7 seconds of transaction execution time due to idle time between statements.

Notice NESTING_EVENT_TYPE | NULl for the BEGIN because it started the whole chain of events, but NESTING_EVENT_TYPE | TRANSACTION for other statements, which agrees with the event hierarchy.

The end event ID for each statement is several events more than the statement because nested within each statement are stages.

Notice that the last statement (COMMIT) has ending event ID 285, which is nested stage event ID and larger than the BETWEEN values used in the query on this table.

We need to use this stage event ID when querying nested stages to ensure we extract all stages.

Stages

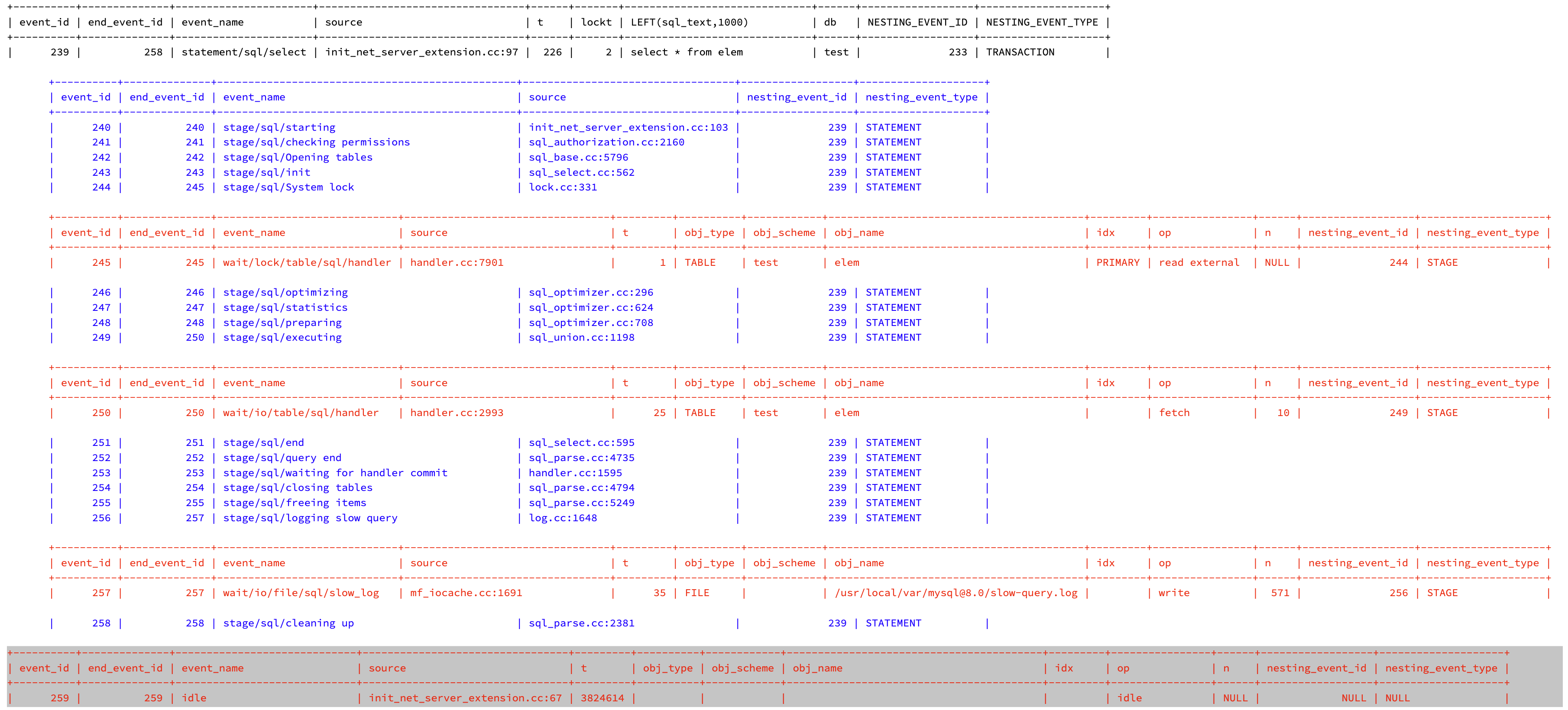

Third, we extract the stages within the statements:

SELECT

event_id, end_event_id, event_name,

source,

nesting_event_id, nesting_event_type

FROM

events_stages_history

WHERE

thread_id=54

AND event_id BETWEEN 229 and 285;

+----------+--------------+------------------------------------------------+----------------------------------+------------------+--------------------+

| event_id | end_event_id | event_name | source | nesting_event_id | nesting_event_type |

+----------+--------------+------------------------------------------------+----------------------------------+------------------+--------------------+

| 230 | 230 | stage/sql/starting | init_net_server_extension.cc:103 | 229 | STATEMENT |

| 231 | 231 | stage/sql/Executing hook on transaction begin. | rpl_handler.cc:1472 | 229 | STATEMENT |

| 232 | 233 | stage/sql/starting | rpl_handler.cc:1474 | 229 | STATEMENT |

| 234 | 234 | stage/sql/query end | sql_parse.cc:4735 | 229 | STATEMENT |

| 235 | 235 | stage/sql/closing tables | sql_parse.cc:4794 | 229 | STATEMENT |

| 236 | 236 | stage/sql/freeing items | sql_parse.cc:5249 | 229 | STATEMENT |

| 237 | 237 | stage/sql/cleaning up | sql_parse.cc:2381 | 229 | STATEMENT |

| 240 | 240 | stage/sql/starting | init_net_server_extension.cc:103 | 239 | STATEMENT |

| 241 | 241 | stage/sql/checking permissions | sql_authorization.cc:2160 | 239 | STATEMENT |

| 242 | 242 | stage/sql/Opening tables | sql_base.cc:5796 | 239 | STATEMENT |

| 243 | 243 | stage/sql/init | sql_select.cc:562 | 239 | STATEMENT |

| 244 | 245 | stage/sql/System lock | lock.cc:331 | 239 | STATEMENT |

| 246 | 246 | stage/sql/optimizing | sql_optimizer.cc:296 | 239 | STATEMENT |

| 247 | 247 | stage/sql/statistics | sql_optimizer.cc:624 | 239 | STATEMENT |

| 248 | 248 | stage/sql/preparing | sql_optimizer.cc:708 | 239 | STATEMENT |

| 249 | 250 | stage/sql/executing | sql_union.cc:1198 | 239 | STATEMENT |

| 251 | 251 | stage/sql/end | sql_select.cc:595 | 239 | STATEMENT |

| 252 | 252 | stage/sql/query end | sql_parse.cc:4735 | 239 | STATEMENT |

| 253 | 253 | stage/sql/waiting for handler commit | handler.cc:1595 | 239 | STATEMENT |

| 254 | 254 | stage/sql/closing tables | sql_parse.cc:4794 | 239 | STATEMENT |

| 255 | 255 | stage/sql/freeing items | sql_parse.cc:5249 | 239 | STATEMENT |

| 256 | 257 | stage/sql/logging slow query | log.cc:1648 | 239 | STATEMENT |

| 258 | 258 | stage/sql/cleaning up | sql_parse.cc:2381 | 239 | STATEMENT |

| 261 | 261 | stage/sql/starting | init_net_server_extension.cc:103 | 260 | STATEMENT |

| 262 | 262 | stage/sql/checking permissions | sql_authorization.cc:2160 | 260 | STATEMENT |

| 263 | 263 | stage/sql/Opening tables | sql_base.cc:5796 | 260 | STATEMENT |

| 264 | 264 | stage/sql/init | sql_select.cc:562 | 260 | STATEMENT |

| 265 | 266 | stage/sql/System lock | lock.cc:331 | 260 | STATEMENT |

| 267 | 269 | stage/sql/updating | sql_delete.cc:561 | 260 | STATEMENT |

| 270 | 270 | stage/sql/end | sql_select.cc:595 | 260 | STATEMENT |

| 271 | 271 | stage/sql/query end | sql_parse.cc:4735 | 260 | STATEMENT |

| 272 | 272 | stage/sql/waiting for handler commit | handler.cc:1595 | 260 | STATEMENT |

| 273 | 273 | stage/sql/closing tables | sql_parse.cc:4794 | 260 | STATEMENT |

| 274 | 274 | stage/sql/freeing items | sql_parse.cc:5249 | 260 | STATEMENT |

| 275 | 275 | stage/sql/cleaning up | sql_parse.cc:2381 | 260 | STATEMENT |

| 278 | 278 | stage/sql/starting | init_net_server_extension.cc:103 | 277 | STATEMENT |

| 279 | 281 | stage/sql/waiting for handler commit | handler.cc:1595 | 277 | STATEMENT |

| 282 | 282 | stage/sql/query end | sql_parse.cc:4735 | 277 | STATEMENT |

| 283 | 283 | stage/sql/closing tables | sql_parse.cc:4794 | 277 | STATEMENT |

| 284 | 284 | stage/sql/freeing items | sql_parse.cc:5249 | 277 | STATEMENT |

| 285 | 285 | stage/sql/cleaning up | sql_parse.cc:2381 | 277 | STATEMENT |

+----------+--------------+------------------------------------------------+----------------------------------+------------------+--------------------+

The output is overwhelming, but there’s a pattern: each statement begins with stage stage/sql/starting and ends with stage stage/sql/cleaning up.

Scroll to the right of the output and look at the repeating blocks of nesting_event_id values: one for each statement by statement event ID:

| Statement Event ID | SQL |

|---|---|

| 229 | BEGIN |

| 239 | SELECT |

| 260 | DELETE |

| 277 | COMMIT |

Executing the actual query (the SQL statement) is just one stage of many. Stages have execution time, too, but I didn’t include it here because I don’t think it’s particularly useful. Why? Two reasons: stages are usually not a problem; and there’s nothing you can do about a slow stage unless it’s the query execution stage, in which case you optimize the query, not the stage.

Waits

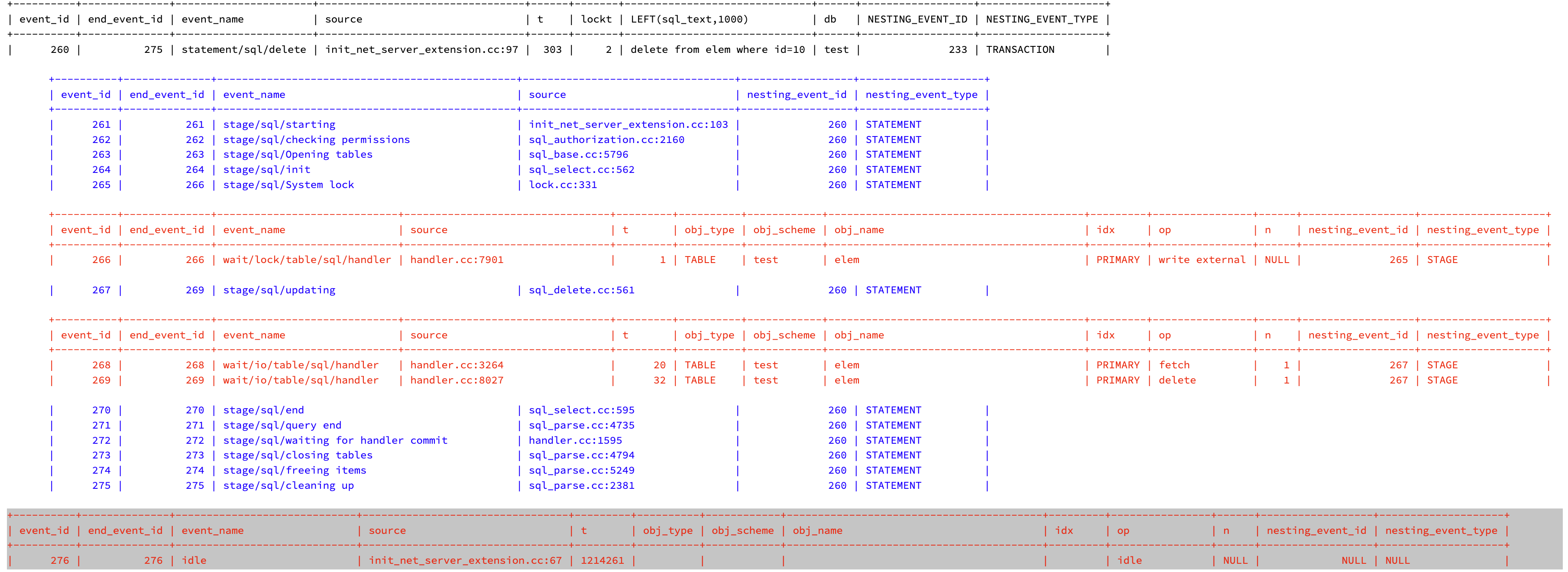

Finally, we extract the waits within the stages:

SELECT

event_id, end_event_id, event_name,

source,

ROUND(timer_wait/1000000) t,

COALESCE(object_type, '') obj_type,

COALESCE(object_schema,'') obj_scheme,

COALESCE(object_name,'') obj_name,

COALESCE(index_name, '') idx,

operation op,

number_of_bytes n,

nesting_event_id, nesting_event_type

FROM

events_waits_history

WHERE

thread_id=54

AND event_id BETWEEN 229 and 285;

+----------+--------------+-----------------------------+---------------------------------+---------+----------+------------+-----------------------------------------+---------+----------------+------+------------------+--------------------+

| event_id | end_event_id | event_name | source | t | obj_type | obj_scheme | obj_name | idx | op | n | nesting_event_id | nesting_event_type |

+----------+--------------+-----------------------------+---------------------------------+---------+----------+------------+-----------------------------------------+---------+----------------+------+------------------+--------------------+

| 238 | 238 | idle | init_net_server_extension.cc:67 | 2688899 | | | | | idle | NULL | NULL | NULL |

| 245 | 245 | wait/lock/table/sql/handler | handler.cc:7901 | 1 | TABLE | test | elem | PRIMARY | read external | NULL | 244 | STAGE |

| 250 | 250 | wait/io/table/sql/handler | handler.cc:2993 | 25 | TABLE | test | elem | | fetch | 10 | 249 | STAGE |

| 257 | 257 | wait/io/file/sql/slow_log | mf_iocache.cc:1691 | 35 | FILE | | /usr/local/var/mysql@8.0/slow-query.log | | write | 571 | 256 | STAGE |

| 259 | 259 | idle | init_net_server_extension.cc:67 | 3824614 | | | | | idle | NULL | NULL | NULL |

| 266 | 266 | wait/lock/table/sql/handler | handler.cc:7901 | 1 | TABLE | test | elem | PRIMARY | write external | NULL | 265 | STAGE |

| 268 | 268 | wait/io/table/sql/handler | handler.cc:3264 | 20 | TABLE | test | elem | PRIMARY | fetch | 1 | 267 | STAGE |

| 269 | 269 | wait/io/table/sql/handler | handler.cc:8027 | 32 | TABLE | test | elem | PRIMARY | delete | 1 | 267 | STAGE |

| 276 | 276 | idle | init_net_server_extension.cc:67 | 1214261 | | | | | idle | NULL | NULL | NULL |

| 280 | 280 | wait/io/file/sql/binlog | mf_iocache.cc:1691 | 19 | FILE | | /usr/local/var/mysql@8.0/binlog.000077 | | write | 295 | 279 | STAGE |

| 281 | 281 | wait/io/file/sql/binlog | basic_ostream.cc:88 | 137 | FILE | | /usr/local/var/mysql@8.0/binlog.000077 | | sync | NULL | 279 | STAGE |

+----------+--------------+-----------------------------+---------------------------------+---------+----------+------------+-----------------------------------------+---------+----------------+------+------------------+--------------------+

I love how the MySQL manual defines waits:

The Performance Schema instruments waits, which are events that take time.

So waits are events that take time… but wait (pun intended), doesn’t every event take time? 🤔

I define waits as time MySQL spent waiting for a shared resource or the client.

Shared resources include storage and network I/O, data locks, and synchronization mechanisms. For example, all storage I/O takes a non-zero amount of time. Even the fastest storage systems have a few microseconds of latency. And pretty much every database has locks and synchronization (like mutexes) that incur a non-zero amount of wait time to acquire, especially under high concurrent load.

Waiting for the client is a special wait event called idle, as reported three times in the output above.

Idle events are described in 10.3.5 The socket_instances Table:

The socket status, either IDLE or ACTIVE. Wait times for active sockets are tracked using the corresponding socket instrument. Wait times for idle sockets are tracked using the

idleinstrument.

A socket is idle if it is waiting for a request from the client. When a socket becomes idle, the event row insocket_instancesthat is tracking the socket switches from a status of ACTIVE to IDLE. TheEVENT_NAMEvalue remainswait/io/socket/*, but timing for the instrument is suspended. Instead, an event is generated in theevents_waits_currenttable with anEVENT_NAMEvalue ofidle.

When the next request is received, theidleevent terminates, the socket instance switches from IDLE to ACTIVE, and timing of the socket instrument resumes.

Waits are normally nested in stages, but the idle event is an exception (scroll right on the output).

For example, the first idle event has ID 238, but what does this correspond to?

Since event IDs are monotonically increasing (per thread), this idle event occurred immediately after statement event ID 229 (BEGIN) that ended at event ID 237:

| Event ID | Event Type | End Event ID |

|---|---|---|

| 229 | Statement (BEGIN) | 237 |

| 238 | Wait (idle) | 238 |

| 239 | Statement (SELECT) | 258 |

Remember: I typed these queries manually, so MySQL was idle for 2.7s (t | 2688899 µs) between the statements, waiting for me (the client).

The other waits in the output are waits on shared resources: two table locks and several disk I/O waits.

These are nested in stage events, but follow the nesting event IDs up the hierarchy and you find that the waits are incurred in (or by) statements.

For example, the last two waits are nested in stage event ID 279, which are nested in statement event ID 277: COMMIT.

Back down in the waits again, columns obj_name and op (short for operation) list what MySQL was waiting on during commit: the binary logs.

There’s more to know about MySQL wait events than I present here. The purpose of this blog post is only to show how to start mining the Performance Schema for transactions. But I’ll say a few more things about waits with respect to MySQL performance.

It’s impossible for there to be zero waits (or zero wait time) because latency is inherit to all computer systems.

As I mentioned earlier, all storage (and network) I/O takes a non-zero amount of time.

Therefore, with respect to waits, the goal is to reduce wait time as close to zero as possible.

This is especially important for the idle wait event (waiting for the client) because it’s caused by the application, so it’s something you can directly address.

Again, read section “Common Problems” in chapter 8 of Efficient MySQL Performance.

In the world of MySQL, using waits in performance troubleshooting is not as common as one might imagine, especially since they’ve been available since MySQL 5.5, which was released 12 years ago (in 2010).

Instead, almost everything you read (or listen) about MySQL performance—including my book—focuses on what MySQL is doing and how long that took—primarily statement events.

We could view these two approaches are two sides of the same coin: execution time vs. wait time.

MySQL is either executing or waiting.

But I think that’s a little misleading because, as the event hierarchy correctly models, execution causes waits: execute → wait.

(The idle wait event is an exception, which is why it is not nested in any event.)

Therefore, if we focus on waits first, there’s not much we can learn from them alone or do to reduce them.

For example, let’s say the Performance Schema reveals that a query spends a lot of time waiting on disk I/O.

If you don’t consider why the query is accessing so much data, practically the only solution is to reduce disk I/O latency and increase disk IOPS by upgrading the storage system.

That might work, but it’s wildly inefficient, probably very expensive, and I assure you that no MySQL expert will suggest this approach.

Rather, the correct and most efficient approach is what my book is all about: query response time.

In this example again, you start by looking that the statement causing the disk I/O waits.

Perhaps you find the query lacks a good index, or has a needless ORDER BY clause, or myriad other reasons that make the statement inefficient, which incurs disk I/O waits.

You can optimize the query almost for free—a lot easier than upgrading the storage system.

In my opinion, waits are useful for MySQL experts doing deep analyses, or intrepid software engineers who really want to dig deep into query response time because waits are part of response time. Either way, MySQL performance is query response time.

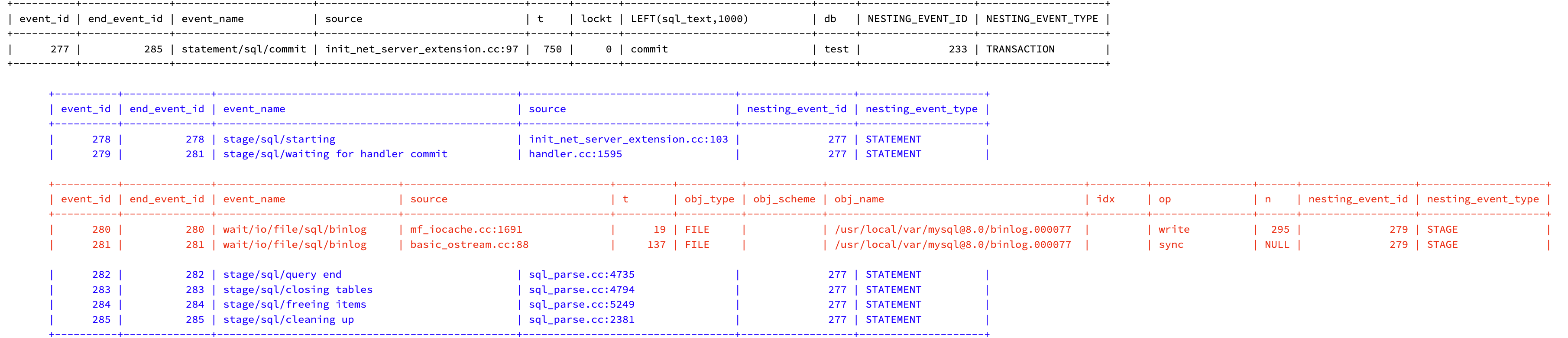

Ingots

The previous section is titled Raw Ore and now you can see why: a simple four-statement transaction yields a lot of raw output that’s hierarchical in the model but flat and kind of mixed up when you query it. To better visualize and understand the transaction, I combined events for each statement and color-coded the output.

Color codes:

- Statement

- Stage

- Wait

- Idle

For example, the SELECT and idle event after begins with the statement event at top.

Underneath that are four stages.

Under each stage are corresponding waits.

And last, an idle event: MySQL waiting for me (the client) to type and enter the next statement.

Click the images to view the full size.

State of the Art

To my knowledge, there are currently no open-source tools that mine the Performance Schema and process the raw data into something easy and useful for human consumption. The MySQL sys Schema has many views that use raw Performance Schema data, but that’s still pretty raw and incapable of expressing a full transaction as shown here. Plus, the Performance Schema has a lot more data than I showed here, so the industry really needs a sophisticated tool that can extract and refine the vast wealth of data in the Performance Schema into gold: deep and practically completely insight into MySQL performance.

But until then, the state of the art with respect to transactions reporting is copy-paste, as I wrote in chapter 8 of Efficient MySQL Performance, reproduced at https://hackmysql.com/trx, and expanded upon in this blog post.

Copyright 2025 Daniel Nichter