Better Replication Heartbeats

Chapter 7

We’ve been measuring MySQL replication lag with heartbeats for more than a decade. It works, but can we do better? Let’s see.

This blog post is the eighth of eleven: one for the preface and ten for each chapter of my book Efficient MySQL Performance. The full list is tags/efficient-mysql-performance.

Replication lag must be greater than zero because networks have latency that is commonly measured in milliseconds. (A local network can have microsecond latency, but I presume MySQL replicas are remote [or in the cloud], so millisecond latency is the norm.) This fact establishes two goals for managing MySQL replication lag:

- Keep lag as close to network latency as possible

- Measure lag with millisecond precision

Goal 1 is primarily the responsibility of the application and its developers, not the DBAs. It’s the reason I wrote chapter 7 of Efficient MySQL Performance: to help app developers understand just enough about the plumbing of MySQL replication to keep lag as close to network latency as possible. Any higher and the risk is unacceptable data loss. Granted, all data loss is unacceptable, but MySQL defaults to asynchronous replication and well… it’s a long, complicated story that’s out of scope for this blog post. The point is: the application and its developers are responsible for replication lag.

Goal 2 is the responsibility of DBAs.

It’s common knowledge that Seconds_Behind_Source (or Seconds_Behind_Master before MySQL 8.0.22) is not reliable.

(If that’s new to you, read chapter of 7 of my book.)

Consequently, it’s been standard practice in the MySQL industry to use external heartbeats (high-resolution timestamps) to measure replication lag.

I say external heartbeats because MySQL replication has built-in heartbeats, but for various reasons they haven’t become the norm for measuring replication lag.

Instead, it’s far more common to use a tool like pt-heartbeat (or program a simpler version of that tool) to periodically write heartbeats on the source and measure the time difference on the replica.

The calculation is lag = NOW() - heartbeat.

If a heartbeat is written on the source at T1 = 1000 ms and observed on the replica at T2 = 2000 ms, then lag is 1,000 ms: the replica is 1 second behind the source.

Sounds simple, but as an engineer you’ve probably already guessed: it’s more complicated than that.

The main issue is when to write the heartbeats on the source and when to measure them on the replica? Until now, practically the only solution has been clock-aligned heartbeats.

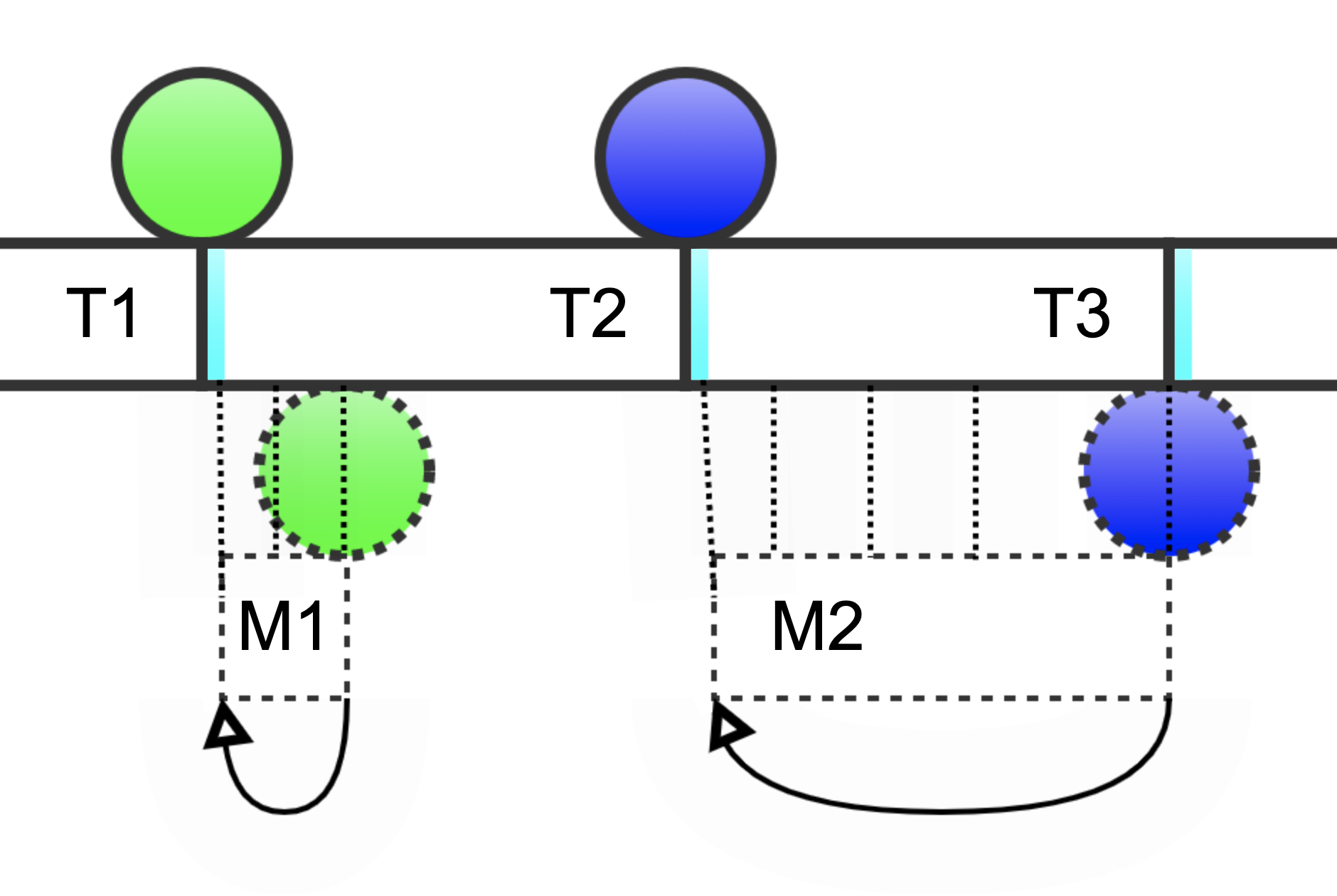

In the following diagrams:

- Colored circles are heartbeats: same color, same heartbeat

- Solid circles at top are heartbeat writes on the source

- Dotted circles at bottom indicate when the corresponding heartbeat arrives on the replica

- Between the two is a time scale from left to right with intervals labeled T0, T1, T2, T3

- Measurements on the replica (at bottom) are labeled M1, M2, M3

Clock-Aligned Heartbeats

Let’s start with diagram 1 (top): clock-aligned heartbeats at 1-second intervals.

Diagram 2 (bottom): Offsets and measurements

Clock-aligned means that heartbeats are written at the beginning (or “top”) of each interval. We’re using 1-second intervals, so clock-aligned is (for example) 12:35:01.000, 12:35:02.000, and so on. Diagram 1 illustrates this with abstract intervals: T0, T1, T2, and T3.

With virtually zero lag, we could write a heartbeat on the source (solid red circle) on read it on the replica (dotted red circle) both at T0. That might be the case on a local network with only a few microseconds of lag, but the more realistic case is illustrated by the green and blue circles. The green heartbeat is written at T1 and arrives (on the replica) a little later: maybe 250 ms of lag. The blue heartbeat is written at T2 but doesn’t arrive until T3: a full second of lag.

Diagram 2 begins to illustrate the current state of the art. The dark shaded areas after the beginning of each interval are 500 ms waits before each measurement (M1, M2, M3). Waits are used for three reasons that, depending on the tool, might not be clear or correct, but here they are:

- Clock skew: If the hardware clocks on the source and replica aren’t in sync, then the skew can artificially increase or decrease the lag measurement.

- Clock-alignment offset: The writer and reader are both clock-aligned, but the writer writes at

Tand the reader reads atT+offsetbecause we can only measure something after it occurs. - Network latency: Replication lag is always greater than zero due to network latency, so there must be some amount of wait to account for the latter.

Waits are not always clear or correct (depending on the tool), but the salient point is: tools wait once, then measure once. Diagram 2 illustrates this, and this section and the next detail the pitfalls of this approach.

It’s common for tools to calculate lag = NOW() - heartbeat - wait because the wait comes from the tool, not replication lag.

However, that means the green heartbeat, which is lagged by 250 ms, is reported a zero lag because it arrived during the wait.

By the numbers, presuming T1 = 1000 ms and the wait is 500 ms, then lag = (1000 + 500) - 1000 - 500 = 0.

That’s why I shade the waits black: they’re black holes of observability.

On the upside, we can say that replication is leas than 500 ms.

That’s better than Seconds_Behind_Source.

Ironically, this approach is most accurate when lag equals the interval, as illustrated by the blue heartbeat: written at T2, not observed at M2, then arrives at T3.

(Ironic because the lag needs to be bad for the accuracy to be good.)

The measurement at M3 reports lag = (3000 + 500) - 2000 - 500 = 1s, which is perfectly accurate.

If the heartbeat had lagged only 700 ms, it would still be reported as 1s because its timestamp is T2 (2000) and it’s not measured until M3.

This approach does not truly measure replication lag; it only reports if lag is less than the wait.

Waiting Less, Work More

“Easy fix,” you say, “just decrease the wait time and the ‘black hole of observability’ virtually goes away.”

Diagram 4 (bottom): 50 ms heartbeats and waits

Diagram 3 is the same situation as diagram 2 but with 200 ms waits instead of 500 ms.

Now the green heartbeat, which lags by 250 ms, does not disappear into the black hole of observability, but we run into the same irony as before: the lag needs to be bad for the accuracy to be good.

The green heartbeat is not observed until M2, so it’s reported as lag = (2000 + 200) - 1000 - 200 = 1s.

The curved arrow in diagram 3 shows that this approach measures lag as the interval from measurement (M2 minus the wait) to when the heartbeat was written (solid green circle). It does not actually measure how long it took the heartbeat to arrive, which is the real meaning of lag.

Diagram 4 illustrates a possible but inefficient solution: write and measure heartbeats at short intervals: 50 ms. This works by brute force: it can measure replication lag with 50 ms of precision. But it’s terribly inefficient, especially given that replication lag should be the exception, never the norm. It’s like (weird analogy) telling someone “Yell every 50 ms to let me know that everything is okay”, instead of just “Call me when there’s a problem.”

Coordinated Heartbeats

Let’s first improve the accuracy and efficiency of replication lag measurement as shown in diagram 5.

Diagram 6 (bottom): Coordinated heartbeats

True replication lag is the difference between the time when a heartbeat is written and when it’s observed on a replica. This is shown in diagram 5 as dotted boxes around M1 and M2. We’ll come back to digram 6; for now, let’s zoom in on diagram 5 shown below.

The small slice of time after the interval in cyan is a wait for network latency. But don’t worry: this does not introduce the same problems with waits described earlier. On the contrary: instead of an arbitrary wait, network latency is meaningful and measurable because there is a finite (and usually pretty steady) amount of network latency between source and replica. A heartbeat cannot possibly arrive on the replica before the minimum latency of the network. Therefore, the cyan time is set to the minimum network latency—no more, no less.

Diagram 7: Zoom in on diagram 5

Diagram 7: Zoom in on diagram 5

Once a tool has waited the minimum network latency, it starts figuratively looking for the heartbeat on the replica. If lag equals the minimum network latency, then the heartbeat will be observed on the first measurement, shown in diagram 7 as the first dotted horizontal line. But in this example, the heartbeat hasn’t arrived yet, so the tool waits a short duration and looks a second time—the second dotted horizontal line. But the heartbeat still hasn’t arrived yet, so the tools waits a short duration and looks a third time—now the heartbeat has arrived (third dotted horizontal line through the center of the dotted green circle). Lag, as shown by the curved arrow, is the difference between when the heartbeat was observed and when it should have arrived (immediately after the minimum network latency). This new approach correctly and accurately measures true replication lag.

The blue heartbeat lags the full interval. What’s important is that the duration between measurements (dotted horizontal lines) becomes longer the more the heartbeat lags. As a result, this approach is accurate in the normal case when there’s little to no lag, and also efficient when appreciable lag occurs. When a heartbeat lags past a certain point (about 1s or so), further precision isn’t needed: lag 1.2s and 2.3s are both bad. Once lag exceeds several seconds, we can measure every few seconds until it returns to near-zero, then resume high-precision measurements. That’s possible with this new approach that (for lack of a better name) I call coordinated heartbeats.

But what makes this new approach “coordinated”? Scroll back up to digram 6 and notice that the time interval labels (T1, T2, T3) are gone. (We could remove T0, too, but time has to start at some time… or does it?) Coordinated heartbeats include a timestamp and the number of milliseconds until the next heartbeat will be written. As shown in diagram 6, the receiver calculates the next interval and waits until then plus the minimum network latency. Heartbeats are not clock-aligned (they occur at any time), and the heartbeat writer coordinates the heartbeat reader.

Paired with accurate and efficient measurements (diagrams 5 and 7), coordinated heartbeats decouple write frequency from reporting accuracy. You can write heartbeats every 2s but still measure and report replication lag with millisecond accuracy. That makes coordinated heartbeats far more efficient overall: less work without loss of accuracy.

To answer the opening question of this blog post, “Can we do better?”, I think the answer is yes: coordinated heartbeats are better. I implemented them in a new open source tool that I’ll announce soon.

Copyright 2024 Daniel Nichter